Rabia Akhtar

Remarks on ‘Pakistan-U.S. Ties’ by Prof. Dr. Rabia Akhtar, Director CSSPR, University of Lahore, given at the Third Public Hearing of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs of the National Assembly of Pakistan on June 21, 2023.

The phrase “past is prologue” originates from William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and is often used to connote the idea that history shapes the future. However, the actual implications of this phrase are more closely tied to the following line: “What to come, in yours and my discharge.” The context suggests that our current moment is predicated upon the entirety of our past. Future outcomes will depend on the choices we make right now. This phrase harbors numerous interpretations. One popular view is that the past serves as a forecaster for the future. By learning from our mistakes, we can circumvent their repetition. An alternative viewpoint is that the past serves as a cautionary tale. Neglecting to learn from history will result in a recurrence of the same undesirable events.

Moreover, the phrase can be viewed positively. It prompts the notion that our actions today are a product of our past, and that our present actions will shape our future. We must, therefore, remain intentional in our decisions and ensure that they facilitate a positive direction for us. Ultimately, the meaning of the phrase “past is prologue” is nuanced and subjective, and is subject to individual interpretation. Nonetheless, it emphasizes the idea that our past significantly determines our future. And in the case of Pakistan-U.S. relations, there is no other phrase which should help Pakistan decide its actions now to steer this relationship.

Let us first take a look at how deep an imprint the U.S. has on Pakistan in a contemporary sense.

Pakistan’s strategic calculations are directly impacted by the U.S. relationships with two key neighboring countries; India and China. In the East, the U.S. strategic partnership with India exacerbates Pakistan’s security dilemma and amplifies its strategic anxieties. In the North, the intensifying great power competition with China is impacting Pakistan’s delicate balancing act with its alliances. This creates a challenging situation for Pakistan in its East and North.

Turning to Pakistan’s western borders, Afghanistan and Iran stand out as two of the most heavily sanctioned nations, bearing the weight of miseries that spanned decades. The U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan was an embarrassment, leaving the Taliban in control after 20 years of fighting them. During this process, Pakistan was the most natural scapegoat. With Iran, Trump’s unilateral withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) has only deepened Iran’s mistrust and determination to pursue the nuclear option. A nuclear Iran with growing strategic relations with India is not what serves Pakistan’s interests.

So no matter where you look, there is no dimension of Pakistan which does not have U.S. imprints and from which Pakistan has not suffered terribly and continues to suffer! You take a 360 degree look, zoom out, and you see a Pakistan which historically has maneuvered brilliantly extremely restricted spaces in its relationship with the U.S. to its utmost advantage. But should the past be the prologue? While the U.S. has the luxury to step aside and say Pakistan has no relevance to it, Pakistan does not have the same luxury because U.S. is still everywhere around it and there is no escape. Therefore, the best way forward is to find convergences and maximize on them and reduce divergences.

Now let us examine what Pakistan must not do to repeat old mistakes. And what must be done now so that the future takes shape? This list is not exhaustive, but this is my top four:

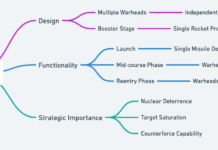

- Sell Pakistan’s threat perceptions well. In the past, we did not do a good job on it. Since hindsight is 20/20, we can see where it did not go well. We were unable to make the U.S. understand why we needed defense partnership with it and we hedged it in joining military alliances like Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) and Central Treaty Organization (CENTO). As a result, when we embarked on our nuclear journey, we had trouble making the U.S. believe the rationale for possession of nuclear weapons at all costs and India being an existential threat. So when the U.S. supplies weapons to India, it directly affects Pakistan and the already fragile strategic stability in the region and pushes Pakistan to do whatever it takes to maintain strategic parity and manage the huge conventional asymmetry which is ever-growing. And in order to do so, Pakistan will naturally look towards China or Russia. And the cycle will go on.

- Pakistan needs to make the U.S. realize that the second order effects of great power competition with China, has Pakistan absorbing all the effects of the strategic chain from top to bottom since it is at the end of that chain. So while it is trying to check China’s assertiveness in the Asia-Pacific, and developing military and defense partnerships, it is affecting Pakistan directly. A crash course on security dilemma sensibility for the U.S. is in order whereby it needs to realize that its actions at the top level trickle down to smaller countries like Pakistan, complicating their strategic calculus.

- It also complicates the U.S. position to talk about strategic stability in South Asia or have any stake in it beyond rhetoric when it is the one feeding the drivers of instability in the first place. So perhaps preaching peace and sanity and having a moral positioning on nuclear taboo would not cut it when the U.S. is not sincerely invested in peace between India and Pakistan.

- The 1965 war serves as the precedent; the U.S. supplied weapons to both India and Pakistan which led to their use in the 1965 war. India and Pakistan both violated the terms of their agreements with the U.S. and that led to the 10 years arms embargo. But it was not as if the U.S. did not know where these weapons would be used given the nature of Indo-Pak hostile relations; it very well knew that, and yet it still supplied them to both countries.

- Fostering economic cooperation, trade, and investment to benefit both countries and provide stability in the region. CPEC is not a zero sum.

- China has never told Pakistan not to bring investors from the U.S. and invest in the Special Economic Zones (SEZs).

- The National Security Policy’s direction of taking Pakistan the route of geoeconomics and making it economically stable to be a better partner for the U.S. ; Geoeconomics is a win-win. But that would only be supported by the U.S. if the US is invested in cooperation and not confrontation. It takes two to tango.

- The Balancing Act: Countries like Germany and Australia are today in the same position as Pakistan, where they have to balance their relations with the U.S. and China given the enormous stakes they have in both countries.

- The balancing that the U.S. expects from its partners, needs to be displayed by itself as well in our region.

- Geography cannot be changed. It is both a blessing and a curse. When the contact happens over Taiwan, India will not pick a side. Neither will Pakistan.

The U.S. is an extra regional force in the region. China is a residential power. While the U.S. has the luxury to leave the region, we (India and Pakistan) are here to stay and therefore building partnerships and coalitions against China with countries that border China is not sustainable in the long term and must be revised. It might benefit countries like India in the short term, where playing the China card gets them the big-ticket defense items from the U.S.; expecting India to use those against China is a U.S. expectation from India which will not materialize.

Dr. Rabia Akhtar is Director, Center for Security, Strategy and Policy Research (CSSPR), and Editor, Pakistan Politico.