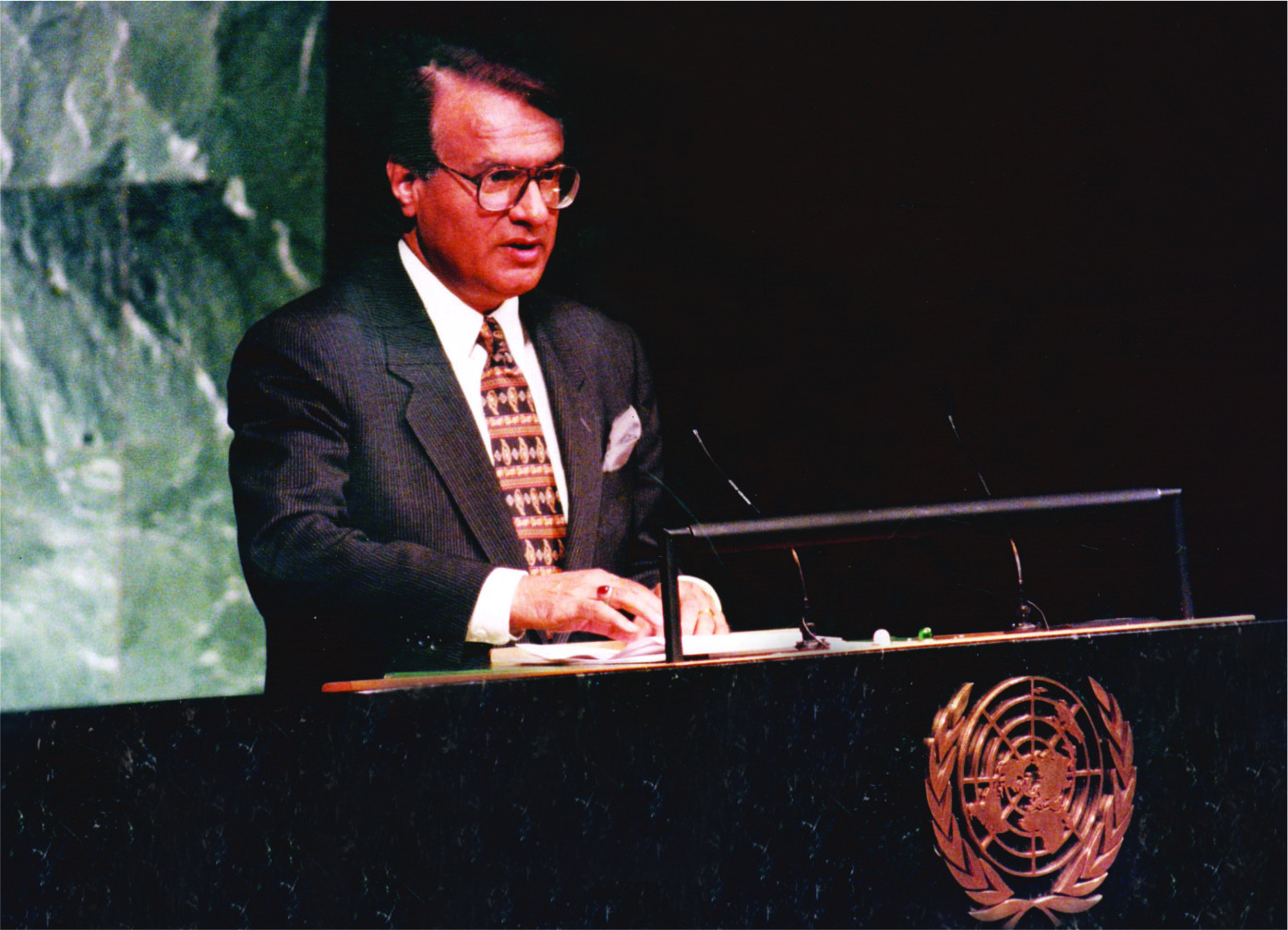

Amb. Shamshad Ahmad Khan is Pakistan’s former Foreign Secretary, who currently is the Chairman of the Lahore Center For Peace Research (LCPR). In his illustrious 4-decade long career, he has held prominent positions, both in the Foreign Office and Pakistan Missions around the world. He was Pakistan’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Pakistan’s Ambassador to Seoul and Tehran. During his career, he was instrumental in expanding the Economic Cooperation (ECO), successfully negotiating the Composite Dialogue with India and led Pakistan in rounds of dialogue with the U.S. from 1998 to 1999. Pakistan Politico discussed with him the broader contours of Pakistan’s foreign policy, his take on the future of the conflicts in Afghanistan and Kashmir, Pakistan’s Middle East challenge, and his new book “Pakistan’s Foreign Policy Dilemma: A Perennial Quest for Survival”.

In your illustrious career spanning four decades, you have served the country meritoriously at various important positions and capitals. Share with us your most challenging and your most rewarding experiences?

On my family’s migration to Pakistan in 1947, I grew up in Lahore, where I went to school in Model Town, and then spent eight years at Government College Lahore, six years as a student and two years as a lecturer. Earned several laurels including GCU’s roll of honour for academic excellence as well as extra-curricular distinctions including as President of Government College Students Union in 1961-62.

After serving as a Lecturer in Government College, Lahore from 1962 to 1964, I joined Pakistan Foreign Service in 1965. During my 37-years of diplomatic career, at professional level, I served in various posts at headquarters in Islamabad and in Pakistan Missions at Tehran, Dakar, Paris, Washington, and New York, and held my country’s top diplomatic position as Foreign Secretary. My ambassadorial assignments included South Korea, Iran, as Secretary-General, Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO), and as Pakistan’s Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the United Nations.

As ECO’s Secretary General, I was instrumental in its transformation from a trilateral entity (Iran, Pakistan and Turkey) into a 10-member regional organization with the induction of seven new members, Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

As Pakistan’s Foreign Secretary, I managed and supervised the country’s foreign policy during an extraordinary period of its history that saw not only the resumption of India-Pakistan peace process in June 1997 in the form of what is now familiarly known as ‘Composite Dialogue’ but also the nuclear tests, first by India and then by Pakistan in May 1998, the Lahore Summit in February 1999 and the Kargil crisis followed by October 12 military take-over.

As Pakistan’s Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the UN, I co-chaired UN’s Prepcom on Financing for Development (FfD) (2001-2002), and also co-chaired UN General Assembly’s Working Group on Conflict Resolution and Sustainable Development in Africa.

Authored Three books ‘Dreams Unfulfilled’ (2009), ‘Pakistan and World Affairs’ (2014) and Pakistan’s Foreign Policy Dilemma (2019).

As one of the country’s most renowned diplomats how do you respond to critics who term Pakistan’s foreign policy as laid-back and beset with adhocism? What, if any, changes are needed in the conduct of our foreign policy in today’s world?

To answer this question, one must have a clearer idea of our foreign policy in the context of its basic goals and challenges. But even before that we must understand the basic concept of foreign policy. Unlike other national policies that keep changing or getting updated periodically if not annually, foreign policy of a country is nothing but the sum-total of the values and norms that must guide its conduct in the comity of nations and of its national interests that it must protect and safeguard in order to preserve its sovereign independence and territorial integrity.

Pakistan’s foreign policy has been determined by its volatile geo-political environment and an exceptionally hostile neighbourhood leaving it with inescapable compulsions of preserving its sovereign independence and territorial integrity. Foreign policy of a country, and the way it is made and pursued is also inextricably linked to its domestic policies, governance issues and socio-economic and political situation.

No country has ever succeeded externally if it is weak and crippled domestically. Even a super power, the former Soviet Union could not survive as a super power only because it was domestically week in political and economic terms. Our domestic weaknesses have not only seriously constricted our foreign policy options but also exacerbated Pakistan’s external image and standing. No wonder, our perennial quest for survival has been as compelling as it has been uncertain.

I don’t think our foreign policy could ever afford to be laid back. Given the magnitude of our regional challenges and shifting global dynamics, we have always had to pursue a proactive foreign policy with constant change of emphasis and nuance in its application. Yes, our foreign policy did have phases of adhocism or inertia because of domestic weaknesses. In the process, Pakistan has encountered unbroken series of challenges that perhaps no other country in the world has ever experienced.

For over seventy years now, we have followed a foreign policy that we thought was based on globally recognized principles of inter-state relations and which in our view responded realistically to the exceptional challenges of our times. But never did we realise that for a perilously located country, domestically as unstable and unpredictable as ours, there could be not many choices in terms of external relations.

To be recognised as a responsible member of the international community, we need to change world’s perception of our country. To be treated with respect and dignity by others, Pakistan has to be stable politically and strong economically so that it can be self-reliant and immune to external constraints and exploitation. We must also restore our global image as a moderate, progressive and responsible nuclear state, capable of living at peace with itself and with the rest of the world.

Lately, we are beginning to see a change in our external image. The new leadership in our country has indeed brought a visible recognition of our policies at the global level. Our foreign policy today is marked by pronounced emphasis on national interests with proactive approach on our principled positions, especially on Kashmir.

For the first time in decades, we recently heard a top world diplomat praising Pakistan for its generosity in hosting millions of Afghan refugees, for its role in Afghan peace, for its contribution to multilateralism and to the UN’s peacekeeping operations. It was indeed heartening to see Pakistan being hailed as a ‘trustworthy and benevolent nation.’ Not too long ago, Pakistan’s name instantly raised fear and concern. And now, the world seems to be looking at Pakistan as a partner in peace and a factor of stability, regionally as well as globally.

“The world should step back and look at Pakistan through a wider frame” was the stunningly positive message that UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres sent across the world at a press conference in Islamabad during his recent visit to Pakistan.

You have long argued that Pakistan’s foreign policy must gear towards making its strategic location an asset rather than letting it remain a liability. How do we go about doing that at a time when realignments and conflicts have vitiated the regional and global environment?

Sure, I do believe Pakistan’s geostrategic location is its strength. This must not continue to be a liability. We could not change our geography, nor escape from its socio-cultural, political, economic and strategic influences. We had to accept and deal with all realities, pleasant or unpleasant, in our neighborhood. In doing so, our sole consideration had to be how to secure our independence and territorial integrity and our socio-economic stability.

No wonder, in 1947, in that intensely bi-polar world, we opted for the global pole that we thought stood for freedom and for democracy. For us, the over-riding consideration in seeking alliances with the West in the 1950s was our need for military and economic support which to some extent we did receive. For the West, it was their concern over Soviet expansionism that made Pakistan crucial in the final stages of the Cold War.

Through those harsh Cold War years, we did not blink despite the intensity and proximity of the Soviet gaze. In the early 1960s, we undertook historic errands on behalf of the US which included the use of our air bases by US spy planes in the 1960s, and a seminal contribution in the early 1970s to the US-China rapprochement. Our experience, however, did not match our expectations.

Earlier when it came to defend ourselves against India in 1965 and then again in 1971, we fought alone and lost half the country, the worst that could happen to any nation in contemporary history. Despite the widely publicized U.S. “tilt” toward Pakistan during the 1971 war, Pakistan felt betrayed.

After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in late 1979, Pakistan was a key ally of the U.S. again and also the front-line state in the last and decisive battle of the Cold War which hastened the collapse of the Soviet Union and its symbol the Berlin Wall. Pakistan played a key role in dismantling what the free world once called the ‘evil empire’ of the former Soviet Union.

Once the war was over and the Soviets pulled out, the U.S. just walked away, leaving the Afghans at the mercy of their fate. We were also left in the lurch with a painful legacy of Kalashnikov culture and millions of Afghan refugees. East Europe became free and democratic. In the years that followed, the U.S. not only turned a blind eye on our strategic concerns vis-à-vis India but also started bringing us under greater scrutiny and pressure for our legitimate nuclear program.

Pakistan was punished for pursuing its vital security interests. Pakistan faced sanctions again for its nuclear tests in response to those by India in May 1998. The events of 9/11 represented another critical threshold in Pakistan’s foreign policy. It was the beginning of another painful chapter in our history. We became a pivotal player in another U.S.-led long war in our region.

Since then, Pakistan was again a close and pivotal ally of the U.S., extending full cooperation in the so-called war on terror. In June 2004, President Bush designated Pakistan as a major non-NATO ally of the United States, a move that in all respects was more symbolic than practical. In the process, we became a battleground of the U.S. war on terror, paying a heavy price in terms of human and material losses.

The only lesson that we should have learnt through all these painful years is that Pakistan’s foremost challenge today is to convert its pivotal location into an asset rather than letting it remain a liability. Unhindered implementation of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) linking Pakistan’s coastal areas with northwest China provides us an opportunity to do so.

On completion, this project will optimize trade potential and enhance energy security in the region. It will directly benefit more than 3 billion people inhabiting China, South Asia, Central Asia and the Middle East. CPEC is indeed a catalyst for regional economic integration. Besides remaining a factor of peace and stability in our region, we are determined to play our role in South Asia’s economic transformation in sync with the global trends of our times.

In a month’s time Nuclear Pakistan would turn 22. You, as Pakistan’s Foreign Secretary back then, were directly involved in decision-making. Talk us through your experiences of the events that led Pakistan to its nuclear deterrent.

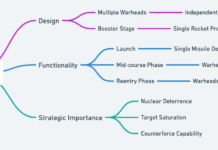

Yes, South Asia was overtly nuclearized 22 years ago. But it was India, not Pakistan that inducted the nuclear dimension into the volatile security environment of this region. Within four years of the NPT’s coming into force in 1970, India carried out its first nuclear explosion (1974) which some in the West also described as “smiling Buddha.” It was indeed the first fatal blow to the NPT regime. Since then India never looked back.

With overt and covert support of the major powers, including the Soviet Union, India continued its nuclear weapon program disguised by deceit. We never challenged the non-proliferation regime when the NPT was being finalised in 1968. In fact, we supported its objectives. We did not sign the Treaty only because India refused to do so and was adamantly pursuing its ambitious nuclear-weapons program. Since the negotiations for the NPT in 1968, in fact, every single non-proliferation initiative came from Pakistan.

In 1974, Pakistan launched a major diplomatic campaign to prevent nuclear proliferation in our region and presented a series of proposals for an equitable and non-discriminatory regime in South Asia. These included a nuclear weapons-free zone in South Asia and mutual renunciation of acquisition or manufacture of nuclear weapons. All these proposals were rejected by India and ignored by the world community.

Our apprehensions were not unfounded. India struck another serious blow to the NPT regime when it conducted a fresh series of nuclear tests in May 1998. On coming to power in March 1998, the BJP government publicly announced its intentions to exercise the nuclear option and to induct nuclear weapons. In April 1998 we sent a letter to the G-8 heads of state and government drawing their attention to India’s nuclear designs.

Our warnings remained unheeded. India’s five nuclear tests on May 11 and 13, 1998, again close to our borders, proved us completely right. We did not respond in a tit-for-tat manner, although we had every legal and political right to do so. India misunderstood our restraint and thought we never had the nuclear capability. Indian leaders embarked upon a nuclear blackmail against us. We knew peace at that time was hanging by a slender thread in South Asia.

We drew the world’s attention to this jingoism. Nothing happened. In fact, we were advised to take the high moral ground not to respond in kind. For 17 days after India’s tests, we waited for the world to do something about India’s threats. Nothing happened. In the absence of any security guarantees, we had to cater for our survival.

Here let me share with you an interesting episode that I went through at that critical moment. Not that I had desired or expected to be there. But I was there leading Pakistan’s Foreign Office at a defining moment in the history of Pakistan – when the country became a nuclear power. The night before Islamabad responded with its matching response, there were intelligence reports that the country’s nuclear facilities were to be destroyed in a joint Indo-Israeli operation. As Foreign Secretary, I woke up the world.

I summoned the Indian high commissioner to the foreign office at the dead of night and told him that if our intelligence reports were true, India should be ready for consequences of unimaginable magnitude. The ambassadors of China, U.S. and Russia were also called to the Foreign Office and briefed of the seriousness of the situation. I requested the Chinese ambassador to verify the situation from none other than the Israeli prime minister Netanyahu who then happened to be on a visit to Beijing.

Netanyahu denied Israeli involvement in any operation against Pakistan. Likewise, Washington took prompt notice of our démarche and had the Israeli ambassador in Washington give similar assurances to our ambassador Riaz Khokhar in Washington. UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan was also informed. Pakistan’s Ambassador to the UN Ahmad Kamal went live on CNN to pre-empt the alleged Indo-Israeli plan.

Kofi Annan’s chief of staff, Iqbal Riza called me early in the morning to convey that UN’s queries showed there was no substance in the alleged reports. Within hours, the tensions dissipated and later in the day (May 27, 1998) Pakistan went nuclear as a result of which the danger of an Indian misadventure evaporated like the winter frost that disappears with the warmth of day. Pakistan exploded five nuclear devices on May 28 and followed that up with one more on May 30.

We had proven our capability. There were no doubts left any more. More than that, our tests restored the regional strategic balance, serving the larger interest of peace and stability in South Asia. As anticipated, however, there was adverse reaction to our tests from the U.S. and other Western countries. They never showed the same reaction over India’s tests.

The formal reaction of the international community, especially the major powers, to South Asian nuclear tests was set out in the UN Security Council resolution 1172 of June 6, 1998 which inter alia, condemned the nuclear tests conducted by India and then by Pakistan. Most importantly, thanks to China’s deft diplomacy, the sequential order used in condemning the tests conducted first by India and then by Pakistan was a significant diplomatic achievement for Pakistan.

The highly nuanced chronological reference in the operative paragraph was recognition of the fact that that the tests were conducted first by India and then by Pakistan. Both countries were asked to resume their dialogue on all outstanding issues in order to remove the tensions between them and to address the root causes of those tensions, including the Kashmir issue.

After their nuclear tests, the U.S. engaged both India and Pakistan separately in a dialogue on an equal footing aimed at nuclear restraint and stabilization. The then U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott held eight rounds of talks separately with India’s External Affairs Minister Jaswant Singh and I between May 1998 and February 1999. As a matter of challenge to our foreign policy during the course of that dialogue, we were able to establish the rationale of our security interests.

The U.S. focus in this dialogue was on persuading both India and Pakistan to seriously look at CTBT and Fissile Material cut-off, export controls and mutual strategic restraint on production and deployment of delivery systems. The question of starting dialogue on Kashmir as called for under UNSC resolution 1172 was also part of the agenda. Barring the issue of export controls, there was little progress on any item. Strobe Talbott has covered the details of this dialogue in his book Engaging India.

After his eight rounds of talks with both countries, a clear nuclear parity was established between the two countries in the form of an implicit “strategic linkage” promising them “equality of treatment” in terms of any future concessions including access to technology. But thanks to double standards prevailing at the global level, that linkage is no longer there now.

You were one of the architects of the Indo-Pak Composite Dialogue of 1997. Based on your first-hand experience, what steps you think can be taken to resuscitate dialogue with India? Is there any space for dialogue in the current environment?

India and Pakistan have had a long history of unfruitful peace processes. In the 50s, as a follow-up to the UN Security Council resolutions, UN Special Representative Sir Owen Dixon tried to negotiate a settlement based on his “partial plebiscite and partition” plan.” In the early 60s, Bhutto-Swaran Singh talks were held without any significant headway. After the 1965 war and in the post-1971 period, internal problems kept Pakistan focused domestically. The 1972 Shimla Agreement created its own dynamics which India always used to assert its own version of ‘bilateralism.’

In the 80s, President General Ziaul Haq gave a fair chance to the Indian approach of “bilateralism and normalization first.” But his visits to Delhi and cricket diplomacy, and subsequently Rajiv Gandhi’s visit to Islamabad failed to produce any results. In the 90s, the Kashmir resistance added a new dimension to the struggle there and brought sharper international focus on this issue especially in the context of human rights situation and the enormous cost of the struggle in human life and limb. During 1990-1994, seven rounds of foreign secretary level talks remained inconclusive.

Within weeks after my assumption of the charge as Foreign Secretary, I was asked to resume the foreign secretary-level talks which I did in March 1997. I visited Delhi and had the first round of our dialogue with my Indian counterpart Salman Haider. Our talks were soon overshadowed by the internal political upheaval in India and remained inconclusive. The Indian side was not willing to make any commitment at a time when the future of their government was uncertain. While I was still there, United Front’s fragile government headed by Deve Gowda faced an imminent vote of no confidence.

When I sat for talks with my Indian counterpart for resumption of dialogue in March 1997, there was no illusion in my mind. Last seven rounds of foreign secretary level talks during 1990 and 1994 had made no headway on the main issues. Both Salman Haider and I expected no miracles. Yet, in our next round in June 1997, we were able to reach an agreement on a peace process familiarly known as the Composite Dialogue with an eight-item agenda and a structured mechanism of working groups to resume the long-awaited dialogue process between the two countries.

I know when we negotiated and finalized this peace process, it was never meant to be an event. The Composite Dialogue was conceived as a process with carefully structured framework to address the whole gambit of India-Pakistan issues including Kashmir and issues of peace and security. Even terrorism was part of our agenda. The period from 1997 to 1999 saw significant developments in India-Pakistan relations in the form of several summit-level meetings between the two countries on the sidelines of the UN annual sessions and other regional and international conferences.

These high-level contacts led to the Lahore Summit in February 1999 where the historic Lahore Declaration marked a genuine breakthrough in the history of the two countries resulting in mutual agreement not only on resolving the outstanding issues but also on nuclear and conventional CBMs including a framework of RRMs for nuclear stabilization. This indeed was a high watermark in India-Pakistan bilateral relations. But the peace process initiated at Lahore was soon interrupted when the two countries faced the Kargil crisis.

The region remained under dark war clouds even after Kargil with India and Pakistan standing at the brink of yet another conflict over Kashmir. An intense diplomatic pressure by the U..S and other G-8 countries then averted what could have been a catastrophic clash between the two nuclear states. A cease-fire at LoC in November 2003 with several mutual confidence building measures led to resumption of the stalled India-Pakistan dialogue in January 2004. The January 6, 2004 Islamabad Joint Statement became the basis for the resumed India-Pakistan dialogue.

Under Pressure from Washington, we gave a solemn undertaking not to allow our territory for any cross-border terrorist activity in future. Whether we meant it or not, India exploited it as our implicit acceptance of India’s allegations of Pakistan’s involvement in cross-border activities. No wonder, since 2006, India has spared no opportunity to implicate Pakistan in every act of terrorism on its soil, including the Mumbai attacks in November 2008 and has kept the dialogue process hostage to its policy of keeping Pakistan under constant pressure.

And that’s where we are stuck today. According to John Kenneth Galbraith, the talks between India and Pakistan resemble badminton. The pattern has been to have talks for a few days in one country, then a few days in the other country, rotating in this manner with each side aiming to get the shuttle in the other country. India has kept the dialogue process hostage to its policy of keeping Pakistan under constant pressure on the issue of terrorism. In a calibrated diversionary campaign, India has only been seeking to redefine the India-Pakistan issues by obfuscating them into terrorism.

Narendra Modi’s arrival on the scene in 2014 further aggravated the situation. He took full advantage of Pakistani leaders’ weaknesses. Driven by anger and frustration, Modi has remained in his hatred-driven chief ministerial mode with a dubious ‘hit-and-miss’ reputation. His obsession with Pakistan was finding manifestation in antics, one after the other, that have brought the region to the brink of another war. He has not only pushed SAARC into a trashy dead end but, since his re-election last year, he also brought India and Pakistan to the brink of another conflict on Kashmir.

What should be clear to Modi by now is that by putting up an arrogant face you cannot change realities. In response to Modi’s brinkmanship, Imran Khan made it clear to him that Pakistan will give a befitting response to any Indian belligerence. His message to India’s Fascist leader was loud and clear: “We will teach you a lesson this time that you will never forget. Let there be no misunderstanding that Pakistan’s armed forces are ready to foil any Indian aggression.” At the same time, Imran Khan assured the Kashmiris that Pakistan will always stand by them.

Kashmir no doubt remains the overarching factor casting shadow on the prospects of peace in the entire region. A solution of the Kashmir dispute will have to be found in a manner that is acceptable to both India and Pakistan and to the people of Kashmir. This requires resumption of India-Pakistan dialogue to build up trust and confidence and an ambiance for mutual discussion on their disputes. Surely, there will be no quick-fixes and perhaps a long-drawn-out process would be inevitable. What we need is an ‘uninterrupted and uninterruptible’ dialogue to turn a new leaf in this troubled equation.

How we conduct ourselves in dealing with India’s RSS-led new fascism is today the most important challenge of our foreign policy. Only a strong and stable Pakistan can withstand India’s belligerence. Weakness always begets indignity. Instead of betraying domestic weaknesses and vulnerabilities, we need to strengthen ourselves to be able to sustain our principled position on Kashmir.

This is what Pakistan demonstrated in its befitting response on 27 February 2019 to India’s latest act of aggression in its territory. Instead of remaining mired in a conflictual mode, both sides must now understand that peace between them is a strategic imperative. They must renounce the use of force for settlement of their bilateral disputes. Steady improvement of relations between Pakistan and India requires further changes in the way they deal with each other. India, being the biggest country in South Asia, must lead the way by removing fears among its neighbours.

How do you assess Pakistan’s response to India’s annexation of Kashmir? As Pakistan’s former Permanent Representative to the United Nations, how do you look the ongoing internationalization of the issue? What is the way forward for Pakistan as it deals with an overly-brazen India?

The illegal and unilateral steps taken by India in Occupied Jammu & Kashmir on 5 August 2019 in contravention of the international law and relevant UN Security Council resolutions have once again brought the entire region to the brink of another conflict.” Kashmir is under siege today. The situation has been exacerbated by the grave human rights and humanitarian fallout of the cold-blooded Indian policy of preventing the Kashmiris from coming out in the streets to protest these illegal actions aimed at changing Jammu & Kashmir’s disputed status as well as demographic composition.

India’s efforts to obfuscate Kashmir dispute as an issue of terrorism will not succeed. Popular movements cannot be suppressed. India will do itself good by seeing the writing on the wall. Stark lessons are there to read in history. Even the world’s sole super power today owes its existence to a long war of independence. Narendra Modi cannot deny the history in his own country. It was the War of Independence in 1857 that laid the road to India’s liberation as an independent state. Kashmir today represents the unfinished agenda of the June 3, 1947 Partition Plan.

India militarily occupied Kashmir through a fraudulent accession extracted from its Hindu ruler in gross violation of the Partition Plan. The people of Kashmir never accepted India’s military occupation and have been waging a relentless liberation struggle. India is forcibly hanging on to Kashmir when the Kashmiris don’t want to have anything to do with India. They consider Indian forces as an occupation force. No amount of atrocities will stop them from pursuing their legitimate cause. Not even the fear of death seems to hold them back.

Theirs is a legitimate freedom struggle against India’s brutal military occupation of their homeland. If history is any lesson, popular movements can never be suppressed. Kashmiri youth are dying today on the streets, not asking for a better future. They are sacrificing their lives while holding the Pakistan flag. It is a verdict they are giving to the world from the streets of Indian-occupied Kashmir. They are struggling for the inalienable right of self-determination that was pledged to them in UN Security Council resolutions.

The setting aside of the UN resolutions is one thing, discarding of the principle they embodied is quite another. The underlying cardinal principle of self-determination cannot be thrown overboard. This is the crux of the Kashmir dispute. Pakistan just cannot compromise on this principle. In this crucial phase of their struggle, Prime Minister Imran Khan has pledged his unstinted commitment to the Kashmiris’ cause as their ambassador to the world.

“We will never abandon the Kashmiris and will continue to support their legitimate freedom struggle. Their cause is our cause”. This is what Prime Minister Imran Khan told the Kashmiris in his 14 August,2019 address at the Azad J&K Assembly. Later, in September 2019, at the UNGA annual session, he woke up the world to the ongoing brutality being perpetrated by Indian occupation forces in Kashmir.

As one of the oldest unresolved international conflicts, Kashmir today is a sombre reminder to the world that it cannot continue to ignore the legitimate aspirations of the Kashmiri people. Unfortunately, the United Nations has washed its hands off in Kashmir by signally to India “it’s your problem.” Imran Khan has now woken up the world. He has placed Kashmir high on the global radar screen. For now, at least, the world knows the illegality of India’s military occupation of Kashmir.

The challenge for us is to sustain the momentum and to keep the world engaged on Kashmiris’ human rights sufferings. Besides drawing world’s attention to untold Kashmiri sufferings, we must strengthen the legitimacy of Kashmiri cause. In doing so, we must focus on India’s repression in the occupied Jammu & Kashmir and on the courageous defiance of the Kashmiri people.

The United States, the sole superpower in the world which bears the responsibility for setting the moral standards globally through rightful leadership also sits back and does nothing. It just remains complacent. On its part, woefully, the Arab and Islamic world too is weak and divided with no role and relevance in global decision-making. OIC’s voice is muted today not only on Kashmir, but even on Palestine and Jerusalem, the very raison d’être of its own creation. In this scenario, the world powers must prevent the impending risk of a genocide in the Indian occupied Kashmir.

They must also avert the risk of an India-Pakistan conflict on Kashmir erupting into a nuclear disaster of an unimaginable magnitude. The UN Secretary General must appoint an eminent person of international standing like Bishop Desmond Tutu or President Jimmy Carter or President Mary Robinson as his special envoy on Kashmir. UN’s human rights agencies, notably the Human Rights Council and Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights must remain engaged to monitor the on-ground situation in Indian-held Kashmir.

Perhaps, it’s also time for world’s living Nobel Peace Laureates to wake up and smell the gunpowder in the streets of Indian occupied Kashmir. We must mobilise their moral weight behind the Kashmir cause. We must also make a serious, well-coordinated effort to obtain ICJ’s Advisory Opinion in support of the unimplemented right of self-determination of the Kashmiri people. We must remain steadfast in our commitment to this principle. The Kashmiris are looking towards Pakistan and need our full political, diplomatic, moral and legal support at every level.

The world powers, including the United States should facilitate a fair and lasting settlement of the Kashmir dispute, fair to the people most immediately involved and fair to their own commitments to freedom and human rights. They must stand on the side of justice and legality. To start with, India must restore normalcy in Kashmir by ending human rights abuses and its ill-motivated efforts to change the nature of the disputed territory through demographic engineering in Kashmir. Revocation of these illegal Indian actions could set the stage for a negotiated settlement of the Kashmir issue.

It is also time for the voices of reason and responsibility — in America, China, Russia, Europe and the Arab and Muslim world — to caution India against militarism. India must ensure strict adherence to UN’s cardinal principle of self-determination. The world must also know that the impending threat of an apocalyptical India-Pakistan conflict is fraught with disaster of an unimaginable magnitude and must be averted at all cost.

How do you look at the recently-signed peace deal between the U.S. and the Afghan Taliban? What should Pakistan do in this fragile period in which the Afghans vie for power? What steps can be taken to avert a 90s-like situation?

Throughout the Afghan war, the fundamental issue had been not so much how this war was being conducted but how it was going to end. A basic lesson of military history ignored in this case was that you never start a war unless you know how to end it. At least till now, Washington didn’t seem to have any calculated thinking, much less a strategy to end the Afghan war that in the first instance was a wrong war to start. No wonder, it became the longest and the costliest war in America’s history which has largely been prolonged not for national interests but by its own inertia.

And the fact remains that opportunities were missed in managing the Afghan imbroglio for good reasons as well as bad, and whatever their consequences, they could have been avoided if a country as chaotic and as primitive as Afghanistan, after Soviet withdrawal, had been treated with greater care and compassion, and assisted in its gradual transition to global standards of conduct and behavior. Obviously, Washington had its own vested priorities as part of its global agenda and in pursuit of its worldwide political, economic and strategic power.

It invaded Afghanistan on the pretext of 9/11 by waging an unrelated ‘war on terror.’ It forced Taliban out of power but never defeated or eliminated them. Despite President Obama’s partial military drawdown, an ominous uncertainty still loomed large on the Afghan horizon. The people of Afghanistan are not the only victims of Afghan tragedy. In fact, the people of Pakistan have suffered more in multiple ways in terms of socio-economic burden, massive refugee influx and protracted conflict in its border areas with Afghanistan.

Peace in Afghanistan is long over-due. The country has been in turmoil for over forty years now. The U.S. may have had its own power-driven compulsions but both Afghanistan and Pakistan have suffered for too long and could not afford another cataclysm. With the drawdown of U.S. forces, it seemed, the process of change in Afghanistan had begun. Since 2014, all eyes were on Pakistan to bring Taliban to the negotiating table. The Afghan Government in particular was keen that Pakistan should use its good offices in persuading the Taliban to join the dialogue process.

We have always been ready to play whatever role we can play in facilitating an Afghan settlement among the Afghan parties in an atmosphere of mutual trust and credibility. In July 2015, we were able to host the first round of talks between the representatives of the Afghan Government and Taliban in Murree. We were not only able to bring the Afghan representatives across the negotiating table but also succeeded in involving the US and China as observers in these talks. Pakistan was at the centre of this unprecedented and constructive move towards Afghan peace.

This was the first-ever direct contact between the Afghan officials and Taliban fighters in 14 years. The atmosphere of the talks was good; the prospects for the second round looked promising. But the forces both in Afghanistan and in the region inimical to Afghan peace managed to undermine the peace talks. Pakistan nevertheless remained committed to the Afghan peace process. We have no vested interest in the Afghan situation other than peace, security, stability and prosperity in the region.

The basic objective of our policy is the preservation of Afghanistan’s independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity, and early return of peace in the war-ravaged country enabling Afghan refugees in our country to return to their homeland. Unlike other regional players which can only divide and destabilize the war-ravaged Afghanistan, Pakistan is the only country with unmatched credentials to facilitate Afghan reconciliation with no selectivity or exclusivity and help unite the country in its peaceful political transition.

In this backdrop, we continued our efforts in support of an Afghan-led effort for durable peace and stability in Afghanistan. It was with our support and help that the U.S. had direct dialogue with Afghan Taliban through their representative Zalmay Khalilzad for its withdrawal from Afghanistan. The agreement signed in Doha (Qatar) on February 29, 2020 between the U.S. peace envoy Zalmay Khalilzad and Taliban leader Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar does raise hopes for the war-ravaged Afghanistan to return towards normalcy.

It is indeed a historic development marking the first step in the right direction. The agreement signifies what Pakistan has been saying since the very beginning of the war, that Afghan peace will come only through a negotiated settlement. In the ultimate analysis, Afghans alone are the final arbiters of their own destiny. We as their well-wishers fully support a reconciliation process that is owned and led by the Afghans themselves.

As Afghanistan’s next door neighbours, we are only interested in its smooth and orderly peaceful transition into a country which is at peace with itself and with its neighbours, free of foreign influences. Because of our historic bonds of blood and ancestry, no other country in the region has deeper stakes in Afghan peace. Unlike some other regional players, Pakistan is the only country with unmatched credentials to facilitate Afghan reconciliation.

There are some forces within the region which can only divide and destabilize the war-ravaged Afghanistan. They are also inimical to genuine peace in Afghanistan always seeking to scuttle the whole process. All neighbouring and regional countries must respect the principles of non-interference and non-intervention, and refrain from using the Afghan soil for destabilizing activities in third countries. Regional rivalries can easily stoke the fires of conflict with regional contenders easily reaching out to rival factions and fueling the internal conflict that can spread to Pakistan.

The Doha Agreement involves four basic elements to be addressed as part of the U.S.-Taliban understanding. These include temporary ceasefire, withdrawal of foreign forces within a fourteen-month period, talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government, and assurances that the Taliban will not participate in or aid others in threatening the security of the U.S. and its allies. The fact that the U.S. and the Afghan Taliban after eighteen months of protracted dialogue have solemnly agreed on these benchmarks is in itself reason for optimism over the prospect of Afghan peace.

Given the complexities of the Afghan culture, no doubt, the intra-Afghan reconciliation process is not going to be a smooth journey. But the Afghans know that this time it’s going to be now or never. They will have to rise above their divisive factional politics to come together and build a lasting peace in their country. Peace, as we know by now, is much more than mere absence of war. Countries not at war with other countries are not necessarily at peace with themselves. Peace today has come to mean more than military conflict between states or nations.

It means peace and harmony within nations. It is this peace from within that the Afghans now need. On its part, Pakistan has always been keen to help unite the country in its peaceful transition. In this context, let me share with you that besides Pakistan’s governmental engagement with the Afghan government and the Taliban leadership, a non-governmental effort known as Lahore Process has also been underway to facilitate the intra-Afghan dialogue. Lahore Center for Peace Research (LCPR) which I represent as its chairman is spearheading this process.

The Lahore Process began with a plenary session in Bhurban (Murree) on June 21-22, 2019 with the participation of over 60 Afghan leaders representing various afghan factions with divergent points of view on Afghan issue, all assembled under one roof. The Bhurban Plenary was followed by a Roundtable dialogue in Islamabad on January 14, 2020, attended by a 13-member delegation led by Haji Mohammad Mohaqiq, Head of Hizb-e-Wahdat Mardam-e-Afghanistan. This was the first in a series of similar intra-Afghan talks that we propose to host in the coming months.

These roundtables will hopefully provide an independent, non-partisan platform to Afghan political parties and their leaders for mutual consultations in support of Afghanistan’s long-awaited peace. The consensus emanating from the Islamabad Roundtable called for sincerity of approach and determined efforts by all Afghan leaders in pursuit of an equitable peace process based on mutual respect, reflecting the aspirations of freedom and justice for the people of Afghanistan regardless of their ethnic, lingual and religious backgrounds.

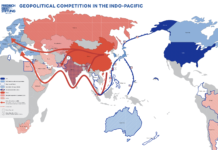

In your view, what could the regional security outlook be after the U.S. withdraws from Afghanistan? How will things shape up for powers like China and Russia? Do you foresee any role for India in Afghanistan’s future?

Henry Kissinger once depicted the Afghan reality in its true character. Afghanistan is a nation, not a state in the conventional sense, and any exit strategy has to be based on the historic reality that the writ of the Afghan government has traditionally been confined to Kabul and its environs, leaving the rest of the country to be run by local warlords or tribal influentials as almost semi-autonomous regions configured largely on the basis of ethnicity, dealing with each other by tacit or explicit understandings. The country is too large, ethnic composition too varied, and population too heavily armed.

Traditionally, therefore, for reasons of its multiple ethnicities and difficult terrain, the country rarely had a strong central government. No army or police force without genuinely reflecting the ethnic reality can deliver in this murky scenario. Whosoever has the power is likely to rule Kabul. As the winds of change blow across this region, Pakistan has to keep itself poised for the role charted by its geography and history that it is required to play in facilitating Afghanistan’s long-awaited peace and stability. It has unmatched stakes in a durable Afghan peace.

No wonder, Pakistan Foreign Minister, Shah Mahmood Qureshi lost no time in urging the need for swift talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government. The U.S. also considers the talks between the government and the Taliban necessary though it knows the process would be “rocky and bumpy.” Already, the Taliban have said that if their 5,000 prisoners held by the government are not released, there will be no talks, even as the Afghan President has noted that release of prisoners is not a condition but will be a subject of discussion in the negotiations.

The experience of centuries, especially of the last three decades, should make one thing clear. No reconciliation imposed from outside will work in Afghanistan. Durable peace in Afghanistan will come only through genuine reconciliation of all Afghan factions and groups with no selectivity or exclusivity. The first step in any roadmap to Afghan peace has to be mutual cessation of hostilities followed in good faith by the exchange of prisoners and withdrawal of foreign troops within the stipulated period. Despite initial hiccups, the Doha Agreement remains intact.

In this backdrop, the Afghan reality has to be understood in its current perspective. The Afghan state is notoriously weak, and Ashraf Ghani’s government remains in power amid much hostility and friction. On the other hand, the Taliban, now recognised by the U.S. as part of the Afghan ‘political fabric’ have gained strength and power and are ready to assume their role with a promised change in their outlook and worldview. Meanwhile, the Afghans are preparing themselves for a new governmental set up with mixed feelings of hope and apprehension.

Beyond the domestic scene, the Afghan theater has multiple external players with conflicting interests. Washington obviously has its own priorities for this region as part of its China-driven larger Asian agenda. Likewise, Russia too as a global power in its own right and as an Asian power, has its own direct stakes in Afghanistan. Lately, in anticipation of U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, Russia has been dealing itself in the game, interacting directly with the Taliban and even attempting to initiate an intra-Afghan dialogue through the ‘Moscow format’.

On its part, China cannot be oblivious of the U.S. counter-weight pressure points in its backyard and must be bracing itself for a balancing role in the region. It has built an unmatched economic and political clout in the region with direct influence in Afghanistan. Similarly, Iran, like Pakistan, has direct stakes in Afghan peace and security. It has been carefully cultivating relations with the Taliban while also preserving its traditional links with components of the former Northern Alliance. The Afghan scene is further aggravated by the ominous Indo-U.S. nexus in the region.

With U.S. support, India has gained an unprecedented influence in Afghanistan which is not without serious implications for Pakistan’s legitimate security interests in the areas bordering Afghanistan. India thus is another regional player with its own ax to grind in the shifting security paradigm in Afghanistan. It has its own concerns over the prospects of Taliban ascendancy in the post-U.S. withdrawal Afghanistan. It is obviously now scrambling to preserve its Afghan assets through the good offices of its friends in the region.

The real challenge now for Afghan peace is to mix deft diplomacy and economic aid. All neighbouring and regional countries must respect the principle of non-interference in Afghanistan’s internal affairs. Regional rivalries can easily stoke the fires of conflict with regional contenders easily reaching out to rival factions within Afghanistan and fueling the internal conflict that has now already spread to Pakistan. It is necessary to control and contain these divisive forces. It is also important that the regional countries do not use the territory of Afghanistan for destabilizing activities in third countries.

To secure a stable, united and independent Afghanistan, there is a need for sharp focus on Afghanistan’s socio-economic development, including trans-regional development. This requires a major role for world’s corporate sector in the development of Afghanistan. It is necessary that the U.S., China and Russia continue to support this process. Together, China and Pakistan represent a natural partnership from within the region that can convert Pak-Afghanistan border into an economic gateway with a win-win situation for landlocked Afghanistan.

You have served in Iran for a number of years. Based on your understanding of both, Iran and the region, tell us how should Pakistan navigate Middle Eastern Faultlines while maximizing its own interests?

Pakistan’s policy in the Middle East is very clear. We do not take sides in any inter-Arab dispute or on any conflict between two Muslim states. This in fact has been a major constant in our foreign policy as manifested in our full support and total solidarity with the entire Muslim world and its legitimate causes. Under Article 40 of our Constitution, we are obliged “to strengthen fraternal relations among Muslim countries based on Islamic unity and common interests.” The only role we can have is one of a peacemaker, not a combatant party on any side or under any compulsion.

We have fraternal relations with all countries in the Middle East, and indeed with the entire Muslim world. We do have military training exchange programs with most of the Muslim as well as other friendly countries. We do have a commitment to meet Saudi Arabia’s security needs, and we are also sensitive to Iranian concerns. Both are our brothers and if Pakistan today is part of a Saudi-sponsored military alliance to fight the common threat of terrorism, there is no contradiction in our commitment to both our brothers. To make things worse, India is playing a spoiler’s role even in this region.

No wonder, continued instability and mutual distrust among the Gulf’s littoral states suits its long-term designs. In this alarming backdrop, all countries in this region especially Pakistan have reason to be concerned over India’s hegemonic designs. For Pakistan, it is of utmost importance that this region remains free of the causes of tensions and instability. Unfortunately, the problem in this region has been the mutual mistrust and fear which in the absence of any regional cooperation system has been aggravating in recent years.

If there was a regional cooperation system between all countries around the Persian Gulf, like the type of cooperation Europeans have been able to develop over the last forty years, there would be no mutual fears in this region. A similar fear existed in the post-World War II Europe about the role of Germany. But they were able to resolve the issues behind this fear through a regional cooperation system. The GCC countries should also rise above their mutual fears and come together forging mutual cooperation by building bridges of trust common interests.

What Prime Minister Imran Khan has recently been doing is only stabilising this process of change in our region. His diplomatic shuttle between Iran and Saudi Arabia was to be seen and understood in this context. Eventually, perhaps, a helping hand will also have to be given to the Muslim world as a whole to recover its lost strength and glory to be able to play a global role commensurate with its size and economic strength. Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan, Turkey, Egypt, Malaysia and Indonesia could perhaps lead the Muslim world to recover its lost glory and clout on the global scene.

This in fact is the crux of the challenge that lies ahead for the leaders of these countries. Together, they have the potential to lead the process of change in the Muslim world. But this requires statesmanship of exceptionable calibre that can rise above vested interests and divisive tendencies to be able to forge a fresh collective impulse that leads the Muslim world into a new era of unity and strength to make it a strong, cohesive global entity in political, economic and security matters. Prime Minister Imran Khan could perhaps play the lead role in mobilizing this effort.

You have recently authored a stupendous and voluminous book on Pakistan’s foreign policy. Could you apprise our readers about the main themes in the book?

Books on history and politics invariably provide nourishment to the quest for knowledge-based awareness of world affairs. There is no dearth of literature all over the world on foreign policy related issues and on matters pertaining to world affairs and international relations. In Pakistan too, the academic vineyard is deluged with textbooks on this subject mostly by authors from the Western world representing a particular shade of opinion. A conditioned, if not prejudiced, opinion on our domestic as well as international issues often confuses the Pakistani mind.

With the exception of few good books authored by my veteran Foreign Service colleagues, we haven’t come across any insightful literature on our own foreign policy and related issues. No wonder, we in Pakistan often misunderstand the realities of foreign policy, especially in the context of its formulation and execution in our own country. My latest book entitled ‘Pakistan’s Foreign Policy Dilemma: A Perennial Quest for Survival’ is a humble effort not only to clarify some of these misgivings but also to facilitate the Pakistani mind to comprehend the peculiarities of our foreign policy.

With the exception of few good books authored by my veteran Foreign Service colleagues, we haven’t come across any insightful literature on our own foreign policy and related issues. No wonder, we in Pakistan often misunderstand the realities of foreign policy, especially in the context of its formulation and execution in our own country. My latest book entitled ‘Pakistan’s Foreign Policy Dilemma: A Perennial Quest for Survival’ is a humble effort not only to clarify some of these misgivings but also to facilitate the Pakistani mind to comprehend the peculiarities of our foreign policy.

Not intended to fill any void in academic minds, this book is only a modest attempt to provide the reader with clearer understanding of the historical evolution as well as contemporary course of our foreign policy in all its aspects. Looking back in retrospect, Pakistan’s foreign policy has been a complex balancing process in the context of the turbulent history of the region in which it is located, its own geo-strategic importance, its security concerns and compulsions, and the gravity and vast array of its domestic problems.

Ours has indeed been a perennial quest for security and survival. The book offers, through a practitioner’s prism, realistic perspectives on our foreign policy for scholars and general readership interested in Pakistan and the region.