Saeed Afridi

Throughout history the Asian continent has been a complex tapestry of competing empires, kingdoms and nomadic people and this has been more pronounced in the region commonly referred to today as Central Asia. Considering the word ‘Asia’ in itself is the result of a European construct with no historical presence in the languages spoken in the continent, as a consequence, definitions of ‘Central Asia’ too are unclear and rely heavily on the definer’s viewpoint and the lack of unifying political centralisation over millennia have left definitions of the region a derivation of various perspectives. Broadly speaking these perspectives can be distinguished as either being Eurocentric or renditions of local and regional empires.

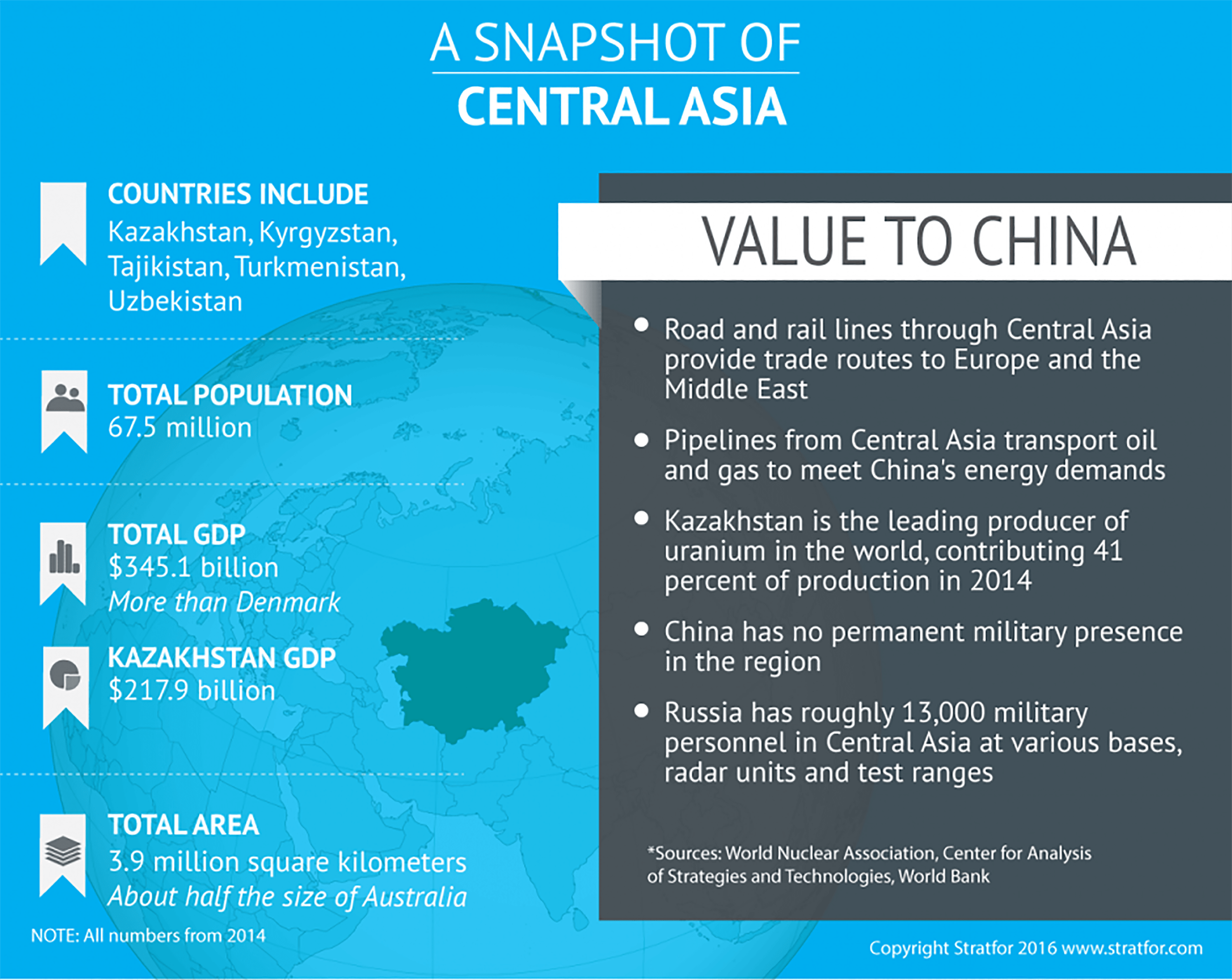

In its comprehensive work on the history of the region UNESCO provided a geographical definition of Central Asia to incorporate the modern states of Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and the North Eastern regions of Iran, Northern India (Kashmir), Western China and Mongolia.

The Western world’s modern understanding of Central Asia is largely a derivative of the great power competition witnessed in the 19th century between the Tsarist (Russian), British, Persian (Iran), Ottoman (Turkish) and Qing (Chinese) empires. British perception of Central Asia derived from East India Company’s ‘defence of India’ traced to the British Empire’s competition with Tsarist-Russia, commonly referred to as the ‘Great Game’, where the areas of contention were largely today’s Pakistan, Afghanistan and the region then collectively referred to as Turkestan. When the ‘Great Game’ ended, Britain had incorporated Pakistan into its Empire and Tsarist-Russia has subsumed much of Turkestan with modern state of Afghanistan emerging as a buffer between them. The Soviet demarcation of the internal borders within the territories it controlled forms the basis of much of the Eurocentric understanding of Central Asia today and was solidified by the post-Soviet independence of the five Central Asian Republics (CARs) of Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan.

For much of the Euro-centric world today, the CARs are the accepted geographical definition and limitation of Central Asia. Western and post-colonial actors like India and Pakistan have formed and implemented policies in the region with this definition in mind.

Turkey, Iran and China, not having been incorporated into colonial empires, have persisted with their perceptions of the region and this has formed an important basis for their policies in the region. Leaving Turkish and Iranian perceptions aside, China’s perception of Central Asia and its geographical boundaries is primarily derived from the Tang Dynasty’s competition with the Tibetan Empire in the region westward of the Yumen Pass, or Jade Gate, in its Gansu Province. This perception sees Central Asia as a region extending westwards from the Yumen Pass to the Caspian Sea, northwards to the Kazakh Steppes and southwards along the Indus river. This perception is instrumental in understanding modern China’s policies in the entire region and its current economic, political and security overtures to CARs, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

This difference in the Chinese perception of Central Asia has become important to understand the post-Soviet competition for the resources of the region and the gulf between the reality and perception of Chinese policies when interpreted by euro-centric commentators, politicians and academics.

For China’s policy makers, Xinjiang is a region deeply embedded in the cultural, economic and political structures of Central Asia and considered a potential flashpoint that can impact the territorial integrity of the Chinese state. While Western and post-colonial actors see Chinese overtures in Central Asia as a mix of mercantile and political expansionism, for Chinese officials and academics they are largely defensive in nature and pivotal for the a mechanisms placed to incorporate Xinjiang into the systemic design of China’s east. Misinterpreting this motivation has been a defining factor of Western commentary on China’s Central Asian economic and security policies.

China’s initial reluctance and subsequent ownership of multilateral platforms for the development of the Central Asian region, like the USAID incubated Central Asian Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC), is borne less out of the need to gain access to resources and more out of its systemic approach to incorporate the countries bordering Xinjiang into the economic structure dependent on Xinjiang and thus the nexus of the Chinese economy itself. Xinjiang, a resource rich region, has over the past two decades become instrumentally intertwined with the resource based economies of Central Asia. With the repackaging of various CAREC related projects in Central Asia and Pakistan into the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI), China aims to further enhance the dependence of these states on the economy of Xinjiang itself. While Western, Pakistani and Indian commentators, academics and politicians have questioned the economic viability of various Chinese projects in the region under the BRI umbrella, and rightly so, a majority of them have misinterpreted the Chinese motivation behind this outreach. China’s policies towards CARs, Afghanistan and Pakistan are less about Chinese promotion of sustainable economic regionalism and much more about China’s internal policies aimed at Xinjiang’s incorporation into the larger system of the state and economy of China.

Xinjiang and the western region of China, including Tibet, are a vast and relatively underdeveloped and underpopulated expanse with a tentative social balance that has for decades been perceived by the Communist Party as unfavourable to the unity of the Chinese state. For Chinese policy makers the implications of the unequal development and possible social unrest in this entire expanse is not merely a matter of economic concern but is overwhelmingly seen through a security related prism. Enabling Xinjiang to become the economic interlocutor between the regional economy of geographical Central Asia, as perceived by China, and the larger Chinese economy is the conduit to first soften and then eliminate the possibility of Xinjiang’s historical ties to the region becoming an existential security threat to the Modern Chinese state.

Given these motivating factors it is important to consider why European, and especially American, models of investigation have repeatedly miscalculated China’s presence and continued progression in Central Asia.

In depth discussions with Chinese academics and officials highlight a perspective on regionalism in particular and international relations in general which does not subscribe to the Euro-centric frameworks of which the United States in particular has been an avid proponent. Unlike most former colonial states in Asia, rather than adapting their own sociopolitical history and regional perceptions to forcibly fit them into dominant Western frameworks, Chinese academics have concentrated primarily at adapting these frameworks for inclusion into the Chinese sociopolitical perspective. In most Western commentary on Chinese policies, especially those considered expansionist, this is a crucial element that has failed to garner the importance it merits. China’s policies towards Central Asia have thus been misinterpreted as military or mercantile expansionist policies while from a Chinese perspective the key motivating factor is and always has been the potential security threat that could destabilise Xinjiang, and thus the Chinese state.

China’s presence in Central Asia has continuously been interpreted in the Western and Western-centric world as its attempt at usurping existing hegemonic structures to establish its own primacy, and in doing so change the contours of political, economic and security related apparatus in Central Asia. While the latter part of this interpretation has merit to it, the former however is largely a mirage. Chinese policies in Central Asia have been carefully crafted to take advantage of existing multilateral frameworks rather than superimpose a Chinese ‘Grand Design’ upon the region. The strategy is adaptive, rather than prescriptive and is motivated primarily through the need to safeguard the territorial, economic and social integrity of political China. Interpreting it through the lens of a prescriptive policy focused on expansionism and resource acquisition alone has led to continuous misinterpretation of Chinese programs and projects in Central Asia as opposed to the actual path being pursued.

Rather than usurp present hegemonic structures and impose a Chinese ‘Grand Design’ to establish hegemony in Central Asia through security, economic and ideological prescriptions Chinese policy makers have consistently considered the economic interdependence of China’s peripheral regions on China’s economy as the primary currency in China’s relationship with these regions; not merely the projection or utilisation of power. The ideological expansion of communist or socialist thought, or for that matter the characteristics of Chinese State Capitalism, are not key concern for them. Therefore the usurpation of the existing hegemonic structures and imposition of one of its own may comfortably fit Western frameworks of hegemony but are not the primary motivation behind China’s Central Asia policy. For China’s policy makers the key is the strengthening of the interrelations and thus the interdependence of the entire Central Asian region, as perceived by China, with the economic activities of Xinjiang, which in turn is fully integrated into the socio-economic system of the remaining Chinese state. Any socio-political unrest in Xinjiang that would threaten the political integrity of the Chinese state would thus have a economically quantifiable adverse effect on the economies of the Central Asian region and thus incentivises the region’s political and business networks, despite historical social and ethnic affinity, to refrain from criticising China’s internal policies aimed at fully integrating Xinjiang into the Chinese state.

While Western academics and policy makers along with their Euro-centric Asian counterparts in Pakistan and India continue to interpret Chinese programs in Central Asia through largely western frameworks analysing hegemony in Central Asia, they will continue to misinterpret China’s largely systems-driven approach which relies on economic interdependency in Central Asia to safeguard perceived security threats in Xinjiang.

Saeed Afridi is an Energy Security Researcher, University of Westminster, UK.