Syed Ali Zia Jaffery

In his seminal book entitled “Nuclear Strategy in the Modern Era” U.S. nuclear scholar Vipin Narang argues that, a mixture of nuclear capabilities, employment doctrine, and Command and Control (NC2), known as a nuclear posture (strategy), engenders deterrence. Narang’s work is a veritable critique of existential deterrence. That said, it is essential to move away from the binaries in this debate given that, even the concept of existential deterrence is fairly incomplete without mutual, survivable second-strike capabilities. Existential deterrence was one of the many concepts that adorned strategic literature during the Cold War, a period that was typified by the two-power nuclear rivalry between Moscow and Washington. However, in the second nuclear age, there are multiple nuclear powers across regions. More importantly, the rough parity in the first nuclear age has been supplanted by general asymmetries in bilateral and trilateral deterrence equations. This, coupled with geographical proximities between regional nuclear states, makes shifts in nuclear strategies more impactful. It is quite possible that, even nuclear states that lack assured second-strike capabilities and survivable deterrents, can make things difficult for big nuclear powers, including the U.S. Other than having an impact on deterrence stability and escalation, the nuclear strategies of regional powers could affect the way the U.S. treats its allies, something which will increase the prospect of nuclear proliferation. There are two opposing reasons that account for this connection.

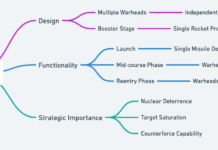

One, how regional nuclear states configure their nuclear strategies will directly affect Washington’s ability to continue providing extended deterrence to its allies. To understand this, an analysis of the multiple-audience problem that both the United States and North Korea face in their nuclear rivalry is important. North Korea’s nuclear weapons enhance the regime’s ability to exercise opposite ends of the coercion spectrum. A complete deterrent, typified by its capacity to hold U.S. cities hostage, augments North Korea’s deterrence vis-à-vis the United States. However, the very completeness of its nuclear weapons inventory raises Pyongyang’s compellence mix in relation to Seoul, or Tokyo, for that matter. Earlier this year, North Korea’s leader Kim Jong Un said his country is producing a range of weapons to bolster its deterrent, to include tactical nuclear weapons. Here, it is worth mentioning that the United States provides extended deterrence to South Korea and Japan. A change in Pyongyang’s capability-spectrum, especially on the battlefields, could open up more avenues for it to exercise nuclear compellence over Seoul and Tokyo. Seeing this, the United States’ extended deterrence commitments will be expected to be made good on. That said, Washington’s bid to stand by its allies in the Far-East will be considerably hurt and discredited, simply because the former cannot risk losing San Francisco by bending over backwards to protect Seoul through a nuclear shield.

This North Korea-induced decoupling will mar Washington’s ties with its allies, signaling them that, when faced with a nuclear behemoth in the hood , they are on their own. U.S. lackluster response could embolden the Kim regime while ensnaring South Korea and Japan in a fear that has the propensity to turn into an existential threat. This will pressure ‘abandoned allies’ to mull over options to deal with a nuclear madman in their region. If Washington’s credibility as a dependable ally, especially when the push comes to shove, is low, Seoul and Pyongyang baring their own teeth cannot be ruled out going forward.

The resultant sense of abandonment on part of allies in the very region will permeate elsewhere, too. U.S. European allies could doubt that country’s commitments and reassurances, things that, among other factors, have kept allies from seeking independent deterrents. The reputational damage will be colossal, to say the least.

Two, on the contrary, U.S. espousal of shifts in strategies, conventional and nuclear, of its allies, will further dent its even otherwise poor, piecemeal nonproliferation efforts. If a U.S. nuclear ally in Israel doubles down on an aggressive strategy, to destroy Iran’s nuclear infrastructure, the U.S. is but likely to support such an effort. Iran, a country that not only distrusts the U.S. and is in the grips of hardliners but also is engaged in a multi-pronged rivalry with both Israel and the U.S., will respond to what it will call yet another, predictable deceit from the U.S. If Iran sees the U.S. as someone squandering the progress towards the reinvigoration of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in favor of punitive kinetic actions, it could be forced to break the shackles of the nonproliferation regime. Iran could leave the NPT, and, slowly but surely, creep towards the bomb. The effect could be a cascading one, for Iran getting a deterrent of its own will provide the incendiary force to Saudi Arabia to follow suit.

Both, the evisceration of extended deterrence and the refusal to give up support for its nuclear allies, will be bad news for the U.S. going forward. It is noteworthy that, in the NPT, the U.S. draws support from countries to whom it provides extended deterrence. U.S. constant support to Israel’s hawkish strategy could push Iran out of the NPT, and its reticence and inability to fulfil its nuclear-related commitments to allies will drive a wedge between the NPT member states. Given that the gulf between the nuclear club and the non-nuclear club within the NPT has widened, as evidenced by the parleys in successive Review Conferences (RevCons), trepidations among U.S. allies will not augur well. Two questions could be asked of the U.S. One, why is deference being shown to a non-NPT, nuclear ally, instead of non-nuclear ones that are party to the NPT? Two, why isn’t the U.S. taking strides towards nuclear disarmament, as stipulated in Article VI of the Treaty? The first and second questions directly link to the purported nuclear conflagrations in the Middle East and the Far-East, respectively. Bereft of enthusiastic support from allies, the U.S. will have to deal with criticisms over its Creating the Environment for Nuclear Disarmament (CEND) proposal and the inflexibility apropos a Nuclear Weapon Free Zone in the Middle East.

All this will undermine the NPT-based nuclear nonproliferation regime, a structure that the U.S. wants to keep intact. Whereas Non-Nuclear Weapon States will continue to remain committed to the NPT and even sign and ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), NPT states that are allied to the U.S. will find it tough to cling on to the NPT and embrace TPNW. This is primarily because the newest treaty to have entered into force outlaws the possession of nuclear weapons for everyone. The corollary will be that some disgruntled allies might decide to take their security in their own hands, instead of relying on a capricious Washington.

Thus, the kinds and types of strategies regional nuclear powers may assimilate in their politico-military toolkit will impinge upon U.S. behavior with their allies. Be it abandonment or a tightening of embrace, the consequences will add to Washington’s proliferation worries.

Syed Ali Zia Jaffery is Associate Editor, Pakistan Politico.