Syed Ali Zia Jaffery

Earlier this year, an unarmed Indian missile fell 124 kilometers inside of Pakistani territory. The Pakistan Air Force (PAF) tracked the entire flight path of the missile but did not shoot it down. The Indian government not only confirmed the incident but also regretted its occurrence, adding that an inquiry would be conducted to ascertain facts. While the characterization of the launch is up for debate, there is no ambiguity in the fact that, absent Pakistan’s restraint, it could have led to serious escalation with far greater nuclear undertones. Pakistan, it must be stated, took a big risk in assuming that the missile is unarmed, and, based on that, decided to let it land on its territory. However, if such an incident were to occur again, in peacetime, or during crises, the response would be different and littered with escalatory risks. This episode does not augur well for future crises between India and Pakistan. There are three reasons why this is the case.

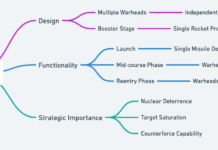

First, as per the available information thus far, the missile was launched during routine maintenance. However, that the missile completed its flight is suggestive of the fact that clamps were removed from it. This raises many a question on India’s maintenance and safety protocols, which, according to India’s Defense Minister, will be reviewed going forward. Such slackness could prove deadly during a crisis. Certainly, chances of panic, miscalculation, and loss of control could increase precipitously amidst the fog of an ongoing crisis. It is worth recalling that, during the 2019 Pulwama-Balakot Crisis, India, thinking it was Pakistan’s, mistakenly shot down one of its own helicopters. The likelihood of committing fatal errors could increase in the next crisis. Most importantly, India’s growing discomfiture with its No-First-Use Policy, coupled with its threats to annex Pakistani territory, may enhance the readiness level of its nuclear forces. Here, it is important to make a mention of India’s Agni-P medium-range ballistic missile. The missile can deliver nuclear payloads at targets in Pakistan with greater speed and accuracy. Further, due to its being canisterized, it would be easier to launch it during a crisis. That canisterization allows for warheads to be permanently mated with the missile is something that could mar crisis stability. Canisterized missiles like this leave little room for mishandling. Thus, during a crisis, an unauthorized launch of a canisterized missile could be cataclysmic. With India keeping its nuclear forces at a higher state of readiness against Pakistan, there is absolutely no margin of error.

Second, India being hesitant to use the military hotline with, and communicate the incident to, Pakistan does not make for good reading. It also raises question marks on the veracity of information that is currently available on the matter. That India didn’t acknowledge the launch until after Pakistan went public is rightly raising concerns about the former’s motives. Was the object of the launch to test Pakistan’s readiness level and air defense capabilities? Did India intend to goad Pakistan into taking reckless actions, with a view to painting it as an irresponsible state? These concerns will remain until and unless more details come out. For now, what lessons has India’s learnt is anybody’s guess. However, Pakistan’s restraint in the past has been dubbed its weakness by India. If New Delhi draws similar conclusions from Islamabad’s inexplicable restraint, it could act more brazenly in future crises. Similarly, the takeaway for Pakistan would be that India either has loose controls over its missiles, or will deliberately up the ante going forward. This will compel the country to raise the readiness level of its nuclear forces. Heightened readiness on both sides, their resolve and willingness to escalate, and an absence of crisis communication would create crisis instability in the next showdown between both nuclear adversaries.

Third, despite being a close-call, the incident hasn’t forced New Delhi to revitalize discussions on nuclear confidence-building measures (CBMs). While it is a good sign that CBMs, like the 1991 Agreement on the Prevention of Air Space Violations and the 1988 India-Pakistan Non-Attack Agreement, have withstood many a crisis, a lot more needs to be done to reduce burgeoning nuclear risks. New CBMs must be explored and discussed, with a view to preventing accidental launches of missiles. However, seemingly, India isn’t eager on expediting the process of inquiry, let alone offering to put in place CBMs.

An early conclusion of the inquiry would have reflected India’s seriousness in disallowing such incidents to happen going forward. The probe’s findings could have become the basis of dialogue on CBMs. Therefore, it is unclear whether or not the inquiry report would contribute towards reducing risks. For it to be impactful, it has to be used as a reference point for negotiating CBMs with Pakistan. Also, so far, nothing has been done to bring temperatures down between the two countries. If anything, India has whipped up its incendiary rhetoric against Pakistan. Senior Indian officials in Defense Minister Rajnath Singh and Home Minister Amit Shah have stressed that they will not shy away from attacking Pakistan. India’s increasing proclivities to use force as well as repudiate dialogue on core issues mean that incidents like this gel well with its political discourse. As a result, the onset of crises would become likelier, and with no new CBMs in the offing, crisis management would become an arduous task.

Moreover, risk-taking from one would mean that the other would be unable to cling to a restrained crisis behavior. Therefore, with both sides committed to taking matters in their own hands, space for third-party mediation would reduce. Further, the lack of condemnation and concern from the international community on the rogue missile does not inspire much confidence in its willingness and capacity to push both countries towards adding more CBMs to the mix. Therefore, little has been done, at this stage, to suggest that such dangerous actions will not be taken during future crises.

Therefore, it is reasonable to argue that, in a volatile environment like South Asia’s, dangerous incidents like India’s March of Madness will only increase nuclear risks. The growing improbability of meaningful dialogue between India and Pakistan, coupled with the presence of crisis-triggers, makes the landscape riskier. Without strengthening CBMs and resolving core disputes, crises will erupt more frequently, and their management will become more challenging than ever.

Syed Ali Zia Jaffery is Associate Editor, Pakistan Politico.