Fahad Nabeel

Since gaining prominence during the 1999 Kosovo conflict, cyber attacks have now become part and parcel of modern-era conflicts, as evidenced by the cyber attacks conducted by state, semi-state, and non-state actors during the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict. Therefore, it would be useful to understand the trends of cyber activities during the said conflict, from the day of invasion (i.e. February 24) until the completion of the second phase of the conflict (i.e. May 12). Here, it is important to point out that the trends of cyber activities can be expected to differ in diverse ways in the third and subsequent phases.

Before analyzing the trends observed in the cyber activities of Russia and Ukraine along with other third parties, it is important to understand that cyber conflict scholarship has its limitations and biases that researchers have to take into account. Joseph Fitsanakis pointed out the following major limitations and biases:

- Resistance offered by adversaries and cyber actors does not get studied

- Wall of classification adopted by government agencies regarding full disclosure of cyber attacks

- Pressure of reproducing dominant narrative propaganda by certain sections of Western media

- Focusing exclusively on non-Western illicit cyber actors

- Temptation to attribute cyber attacks in a knee jerk reaction

These limitations notwithstanding, it is important to discuss the Russian approach in cyberspace and explain how it is in accordance with its past behavior. Also, understanding Ukrainian reliance on the mobilization of international support and formation of a ‘cyber army’ is critical. Additionally, dissecting the role of some third parties, especially Belarus and China, is instrumental in assessing the cyber dimension of the conflict.

Russian Approach

Russian cyber attacks in Ukraine can generally be grouped into three categories i.e. confidence-based attacks, capabilities-based attacks, and control-based attacks. Confidence-based attacks refer to those cyber attacks that undermine public confidence in government’s ability to protect the citizenry and ensure provision of essential services. In the first week of March, Russian cyber actors allegedly were involved in launching DDOS attacks (attacks in which website servers are flooded with traffic to the point that they become unusable) against Ukrainian defense ministry websites. Similarly, Russian cyber actor FancyBear was found involved in conducting a phishing campaign against a Ukrainian media company, UkrNet.

Capabilities-based attacks are those attacks in which you undermine the adversary by employing and leveraging cyber weapons to take access of critical infrastructure and bring down capabilities of the adversary. A case in point is when Russian troops were entering eastern Ukraine on February 24, hackers, allegedly from Russia, crippled tens of thousands of satellite internet modems in Ukraine and across Europe. Considered as one of the largest wartime cyber attacks, it caused a major loss of communication at the outset of the conflict. During the first phase, Russia’s prominent cyber actor, Sandworm, largely remained absent due to unknown reasons. However, the group made its presence felt during the second phase when it was revealed that the group had attempted to cause an electricity blackout through a malware (malicious software) which could have impacted two million people.

Control-based attacks refer to cyber-physical attacks in which the objective is to gain control of adversary’s critical infrastructure. In this regard, two prominent cyber attacks stand out. On March 1, a missile strike on Kyiv’s TV tower coincided with cyber attack against Kyiv-based media firms. Few days later, when Russian military occupied Europe’s largest nuclear power station – Zaporizhzhya station – a Russian cyber actor was detected within networks of a Ukrainian nuclear power company.

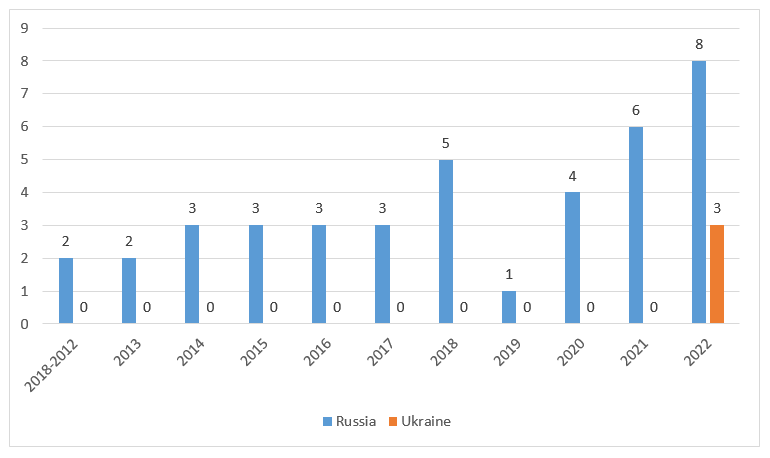

The types of attacks which Russian cyber actors have launched in Ukraine are in line with their behaviors in cyberspace for more than a decade since Russian cyber attacks against Estonia (See Figure 1). Apart from Estonia, entities in Georgia and Ukraine have previously been subjected to these cyber attacks.

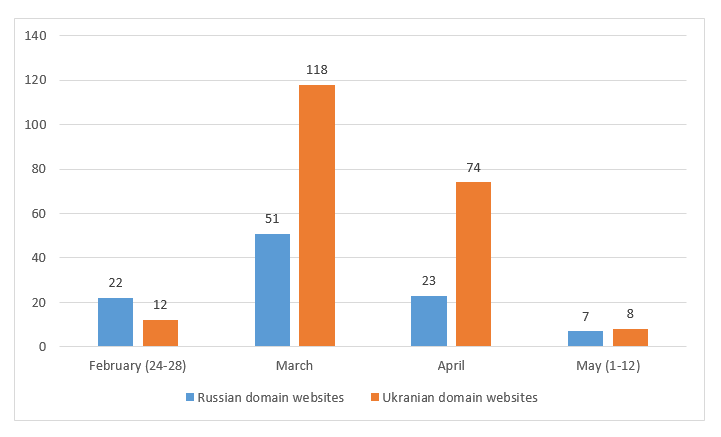

In terms of website defacements, Zone-H, an archive of defaced websites, has documented that about 210 Ukrainian domain websites were defaced (See Figure 2). However, it is important to clarify that it cannot be said how many of them were defaced by Russian cyber actors. Since the invasion, a popular argument has been made about the limited large-scale cyber attacks by Russian cyber actors. However, there are two key reasons – higher efficacy of kinetic attacks and difficulties of planning and executing cyber attacks on a short timeline – behind such an approach.

Fig. 2 – Monthly breakdown of defaced Russian and Ukrainian domain websites (Source: Zone-H)

Ukrainian Response

To counter Russian cyber activities, Ukraine adopted a two-pronged strategy by mobilizing international support and creating an army of cybersecurity professionals, known as ‘IT Army of Ukraine’. The IT Army, which is estimated to have more than 400,000 volunteers, is divided into two units i.e. defense unit (responsible for safeguarding Ukrainian critical infrastructure) and offensive unit (tasked with conducting cyber espionage operations against Russian troops). This government-led initiative coordinated hacktivists and multiple hacktivists groups to launch DDOS attacks against Russian banks and defaced/DDOsed of Russian government websites. The IT Army has been provided a list of more than 30 targets that include large firms supporting Russian critical infrastructure.

On the other hand, prominent group of decentralized hacktivists, Anonymous, declared ‘cyberwar’ against Russia. The hacker collective has claimed to hacked major Russian broadcasters and streaming services by broadcasting clips from Ukraine conflict. Moreover, pro-Ukraine hacktivists are suspected to have used wiper (a type of malicious software that erase data from the hard drive of the computer it infects) to target Russian entities.

Meanwhile, Western tech firms have come to the rescue of Ukraine in various ways. Google expanded eligibility for its free service protection against DDOS attacks, Project Shield, to Ukrainian authorities. Currently, more than 150 Ukraine-based organizations are using this service. Other tech firms like Microsoft are identifying threats to Ukraine while also patching vulnerabilities and sharing information. Media reports suggest that cyber defensive teams from the United States and Britain were already in Ukraine since December last year. Following the invasion, Ukraine called on hacktivists to defend the country from Russian cyber actors. According to Zone-H, about 100 Russian domain websites were defaced (See Figure 2). It is unclear how many of them were defaced by Ukrainian cyber actors.

Role of Third Parties

Apart from Russian and Ukrainian cyber actors, Belarusian cyber actors were also found involved in carrying out activities in the cyber domain. Belarusian cyber actor UNC1151 was detected installing a backdoor (an undocumented way of gaining access to computer system) onto Ukrainian government systems. Similarly, the cyber actor was also involved in launching phishing campaigns against Polish and Ukrainian government and military organizations. On the other hand, China-based cyber actor ‘Mustang Panda’, which is heavily focused on Southeast Asian targets, uses the situation in Ukraine to target European entities through lures in the form of malicious attachments.

Future Trends

In case of a prolonged conflict, the possibility of spillover cyber attacks cannot be ruled out. In this regard, it is important to understand that Russian government’s cyber actors might not necessarily engage in spillover cyber attacks due to Ukraine-related cyber activities. However, there is a possibility that Russian hacktivists groups might be involved in launching cyber attacks against the United States, EU, and NATO countries (specifically Poland, Romania, etc). In this regard, the type of cyber attacks that Russian cyber actors might deploy is likely to be DDOS attacks.

Another key factor that might determine the extent to which Russian government’s cyber actors might get involved in launching cyber attacks beyond Ukraine is the stabilization of Russian military engagements in Ukraine. The retaliatory cyber attacks on the United States and EU entities by Russian cyber actors will likely fit in a five-point test that ranges from not targeting entities that can be viewed as act of war by victims to avoiding to target those entities that might possibly escalate the overall situation. Therefore, there is a strong possibility that five types of entities – financial services, educational institutions, retail, local governments, and small federal departments/agencies – are likely to be targeted by Russian cyber actors.

However, the overall impact of cyber attacks on the ongoing conflict can be truly determined once the conflict comes to an end. Until then, it is important for watchers of cyber conflict to examine the behaviors of cyber actors with skepticism.

Fahad Nabeel is Research Lead, Geopolitical Insights and Visiting Lecturer, National Defence University.