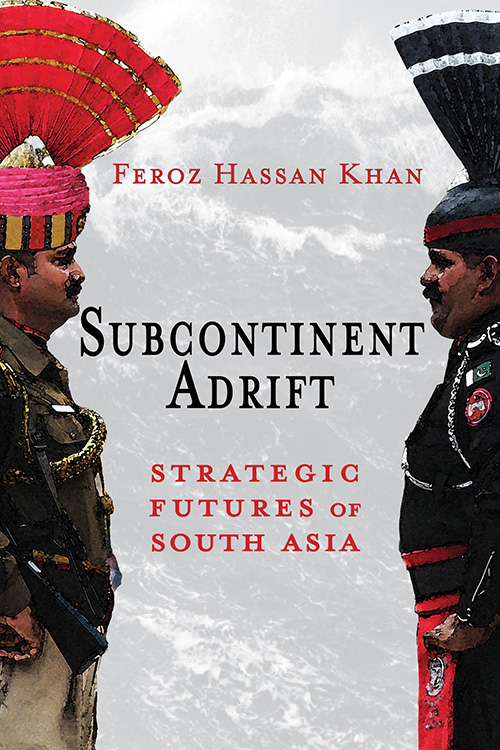

Book Title: Subcontinent Adrift: Strategic Futures of South Asia

Author: Feroz Hassan Khan

ISBN: 9781621966487

Publisher: Cambria Press, 2022

Syed Ali Zia Jaffery

In his 2004 classic titled ‘The Idea of Pakistan’, one of the foremost authorities on South Asia, Stephen Cohen, lamenting the logjam in Indo-Pak relations, argues that, a “peace process between India and Pakistan should attempt to redefine the issue from its fossilized debate over sovereignty, law, and constitutional rights, which leads nowhere, to a search for an improvement in the lives of Kashmiris—Hindu, Muslim, and Buddhist.” Cohen, who spent decades studying India, Pakistan, their militaries, and the overall state of their relations, understood how this acrimony mars peace and stability in South Asia. Indeed, one of the reasons as to why the dividends of integration have eluded South Asia is the animosity between nuclear-armed Islamabad and New Delhi. Therefore, Indo-Pak relations have kept scholars and practitioners around the world busy. Whereas academicians and think tankers have written extensively on the effects of the region’s nuclearization, officials in important capitals, not least Washington, have acted as crisis managers in nuclear-tinged crises between India and Pakistan. That South Asia has suffered because of Indo-Pak hostilities is reason enough to understand the factors that underpin them. With both nuclear states home to about 1.6 billion people, the future of their rivalry is closely tied to that of South Asia.

In order to identify future trends in South Asia through a rigorous assessment of Indo-Pak relations, it is critical to ask and answer this question: What stops New Delhi and Islamabad from taking tangible steps towards normalizing their relations and reaping the economic benefits of connectivity and integration? Combining his military experience and 20 years of scholarship, Feroz Hassan Khan attempts to deal with this puzzle in his new book entitled ‘Subcontinent Adrift: Strategic Futures of South Asia’. This book is a product of a two-decade-long research journey of the author, who was encouraged by Cohen to delve into the causes and consequences of the festering conflict between India and Pakistan. Here, it is noteworthy that, by virtue of dealing with India as a combatant, policymaker, and scholar, Khan is poised to look at the Indo-Pak conflict through many a prism. Additionally, his being associated with U.S. think tank and academic communities has given him an opportunity to add diverse perspectives and nuances to his research.

Khan addresses the aforementioned concern by arguing that, both sides continue to cling to their maximalist positions. He writes that, “India and Pakistan are both hostages to stubborn fixations- one of a rising power seeking its place in the sun, and the other of a nation seeking parity with its mightier neighbor.” Khan, whose seminal work entitled ‘Eating Grass: The Making of the Pakistani Bomb’ shed light on how the Action-Reaction model between India and Pakistan played out in the latter’s nuclear excursion, attributes this competition to cognitive bias and unresolved disputes. The author rightly dubs these two phenomena responsible for making this South Asian conundrum all the more intractable. If anything, deep-seated biases, undergirded by religious fervor, feed into Indo-Pak disputes, and, in the process, make them difficult to resolve. As the author compellingly argues, Islamabad and New Delhi believe that one’s gain is the other’s loss. This line of argument is noteworthy, not least because of two reasons. First, for nuclear watchers, it explains why Robert Jervis’ Nuclear Revolution does not do a good job in assessing the Indo-Pak nuclear dyad. The security dilemma, which, according to Jervis, attenuates due to the possession of nuclear weapons, still lies at the heart of this decades-old competition. Two, economic connectivity can only deliver the goods if all actors commit to not playing zero-sum games. However, to its credit, Pakistan has invited India to partner it in jumping on the advantageous connectivity bandwagon, but the latter has not only ignored such overtures but also gone the extra mile in subverting the former’s bid to bolster regional connectivity. Khan does discuss such subversive activities in a chapter on Gray-Zone Warfare.

For Khan, these anti-progress developments become all the more worrisome, simply because they are happening under a nuclear shadow. He asserts that, “operational nuclear deterrents have signally failed to resolve the fundamental irritants in the bilateral relationship.” While the author is rightly worried about the precipitous increase in the drivers of Indo-Pak crises in spite of the presence of nuclear weapons, it is important to understand that the nuclear dimension is but an offshoot and consequence of the overall confrontational nature of Indo-Pak relations. However, Khan tries to unpack the unstable Indo-Pak security competition, with a view to understanding the future of South Asia and its strategic stability.

Adopting a levels of analysis approach, Khan looks at factors that reduce the prospect of peace between India and Pakistan at the systemic, bilateral, and domestic levels. At the systemic level, Khan is concerned about the trepidations that Sino-Pak strategic relations and the Indo-U.S. bonhomie cause in India and Pakistan, respectively. Here, it is important to mention that, while Pakistan has tried its best to allay Indian fears of encirclement by it and China, the latter has, by resorting to jingoism and threatening to annex the former’s territory, made the former more suspicious about what New Delhi wants to do with Washington’s big-ticket defense articles. Khan’s brilliant analysis of bilateral and domestic impediments help assess the antecedents of both countries’ strategic anxieties. For example, while analyzing one of the major hurdles in bringing about peace at the bilateral level, Khan contends that, seemingly, “India is looking to expand economic cooperation with everyone but its western neighbor.” This attitude on part of India, coupled with its considering Pakistan as a thorn, makes the latter uncomfortable and see that country as a regional hegemon that is trying to defeat it. Khan trying to make sense of why this has been the case makes this work enriching. According to him, sets of structural issues in India and Pakistan have further vitiated the environment. Apropos of India, Khan identifies four bulwarks, out of which the preponderance of India’s strategic enclave and the rigidity of its bureaucracy are instructive, primarily because they scuttle efforts to change the status quo for the better. As for Pakistan, two of the three minefields discussed by Khan must be removed. First, Pakistan must curtail its reliance on outside powers. Absent a commitment to doing that, Pakistan cannot tread the path towards sustainable development and guard its sovereignty. Second, the balance of authority between power centers inside of Pakistan must be altered so as to enable the formulation and execution of coherent long-term policies and strategies. All in all, Khan argues that a levels of analysis approach has helped put on the table a number of challenges to strategic stability in South Asia.

Further, Khan, with a view to exploring more catalysts of the drift on the Subcontinent, discusses New Delhi’s and Islamabad’s attempts aimed at devising their grand strategies. After adroitly parsing elements of India’s Indira and Gujral Doctrines, Khan stresses that the country’s “quest for a viable grand strategy continues.” Though the author does talk about the rise of Hindutva-driven policies, it is important to critically analyze how they could deleteriously affect India’s ability to make a pro-peace, development-oriented, and forward-looking grand strategy. As for Pakistan, Khan, apart from being critical, is mindful of the dilemma that the country faced and still faces. Khan is on the money in arguing that, Pakistan’s grand strategy, which relies on both internal and external balancing, is centered on ensuring its survival and viability. However, Khan arguing that, so long as Pakistan’s grand strategy continues to frustrate India’s objectives, Pakistan’s sovereignty to determine its future would be guaranteed, is a tad problematic. The purpose of Pakistan’s grand strategy must be grander and multidimensional. In the past, by only focusing on countering the Indian threat, Pakistan had restricted the space to maneuver its way and accumulate power. While India will and must remain as an important foreign policy concern for Pakistan, it should not be allowed to become the most important determinant of the country’s policy choices. For Pakistan to thrive, not just survive, its policymakers need to think big and take decisions that lead to sustained, long-term betterment, which the author alludes to later on.

Next, Khan wears his military hat, to understand the implications of the promulgation of incendiary military doctrines by India and Pakistan. After succinctly analyzing India’s provocative Cold Start Doctrine, Khan adds to the scant literature on Pakistan’s Army Doctrine 2011: Comprehensive Response, arguing that, both Indian and Pakistani armed forces are “on a perpetual war footing against each other.” That the levels of war feed into each other in South Asia is something that makes enhancing conventional deterrence all the more critical. Therefore, Khan’s analyses of the South Asian conventional domain are timely and useful for scholars and practitioners alike. Based on all this, it is reasonable to argue that the author is correct in warning about the disastrous effects of India’s limited war fantasies. According to Khan, “India’s limited war could quickly deepen and broaden within just a few days. Consequently, the moment Pakistan sees India shifting gears from peace to war and India’s offensive corps mobilizing, the entire Pakistani armed forces would brace for total war.” Indeed, such an eventuality cannot be ruled out given that many a factor is rigged against substantive dialogue and mediation. Added to this set of complexities is the increase in the intensity of Gray-Zone Warfare. At a time when India’s politico-military leadership is becoming increasingly risk-acceptant, the author is rightly cognizant of the strategic ramifications of using Gray-Zone tactics.

All this, according to Khan, can lead to three scenarios and paths going forward: good, bad, and ugly. By the look of things, India and Pakistan are likely to tread the ‘bad’ path, characterized by tensions and a slow arms race. As for ‘good’ and ‘ugly’ paths, it is important to note that, while Pakistan’s acquiescence (read subservience) to India should be ruled out outright, its accommodating the latter by freezing core disputes is a tough ask, too. This is because the India of today has grandiose aims and is unhappy with what it has right now. Pakistan’s strategic planners must, however, wargame each scenario and work out different permutations. This book is an essential read for not only Pakistani officials involved in doing all this but also for academicians and citizens of India and Pakistan, for they are the victims of instability and beneficiaries of peace between the two South Asian titans.

Syed Ali Zia Jaffery is Associate Editor, Pakistan Politico.