Source: Tribune India

Joshua Bowes

In the shared Himalayan border region between China and India, change is coming. After six decades of violence and disagreement that caused deep geopolitical tensions along the Sino-Indo border, New Delhi and Beijing agreed to militarily de-escalate the conflict in late October 2024. The move is likely to have a plethora of implications on both their bilateral ties and the broader South Asian security environment.

Immediate Implications

The disputed 3,440km border between Asia’s two behemoth nations has festered tension for years. The borderlands’ snow caps, rivers, and lakes are often susceptible to changing weather conditions, meaning soldiers from both sides often confront one another not knowing what the exact lines of division are. Minor clashes erupted in 2021 and 2022 in Sikkim and Tawang, respectively, but the agreement to de-escalate comes four years after violent clashes in Galwan Valley killed 20 Indian soldiers and four Chinese officers. The move was streamlined on October 23 when Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping met on the sidelines of the BRICS summit in Kazan, Russia.

Along the contentious Line of Actual Control (LAC), details about the specifics of the agreement continue to emerge, but the immediate impact of the disengagement appears to concern some level of troop recall and the dismantlement of infrastructure in Depsang and Demchok, near the disputed high-altitude area of Ladakh. The agreement also pertains to military patrolling arrangements. As a result of China’s military operations in 2020, India lost access to nearly 65 percent of its patrolling points. Used to affirm territorial claims, military patrols occasionally resulted in violent standoffs, meaning that a stepping back from aggressive sentinel movements will surely decrease the risk of lethal ground-level confrontations between China and India, and therefore, reduce the likelihood of a larger conflict.

As such, both India and China could reallocate their LAC troops to areas of other concern like the Indian Ocean and South China Sea, perhaps signaling a shift in military posturing. On the whole, the resolution will be viewed by the international community as a positive move long in the making, softening China’s image and perhaps catalyzing later discourse on de-escalation in other potential flashpoints.

Regional Implications and Impact on Economic Ties

For India, the agreement will be seen as a victory. Modi has previously been accused of ceding India’s northern lands to China. Therefore, the move to disengage will likely be somewhat of a celebration for New Delhi. While India and China will remain locked into a competitive battle for regional power and influence, the agreement could bring about stabilized business ties and an aptitude for greater economic collaboration. China is India’s largest trading partner, meaning a stable border could galvanize easier trade relations. In 2023, bilateral trade between Beijing and New Delhi soared to over $136 billion, a 1.5 percent increase over the previous year, supported by a six percent rise in Indian exports to China. Indian companies have established a foothold in China, particularly in the pharmaceutical and manufacturing industries. Chinese companies have likewise made inroads in the infrastructure and electronics industries in India, suggesting increased interdependence and a shared growth.

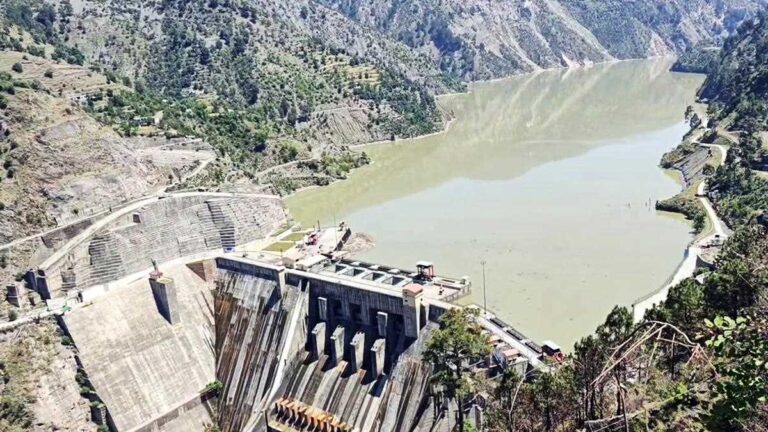

While China and India work through the specifics of their disengagement agreement, Pakistan looks on with bittersweet feelings. Islamabad will be satisfied with the decision to move towards stability, particularly if, in the long term, the security environment of the Himalayas brings about smoother developments of the enormous China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). For India and Pakistan, the LAC resolution might set a precedent for the unresolved dispute over Kashmir, but Islamabad might also be wary that it could be marginalized in the event of a broader movement towards peace solely between China and India.

Regional Frameworks and Strategic Realignment

Despite the potential for stabilized economic relations, New Delhi has gradually moved towards greater alignment with the West through the Quadrilateral Strategic Dialogue (Quad, for short) alongside Washington, Tokyo, and Canberra. Also, recently, the Quad Ports of the Future Partnership was launched, aiming to establish multilateral resilient port infrastructure and challenge Beijing’s southerly expansion towards the Pacific Islands.

While the recent LAC agreement delineates a capacity for political-economic stabilization, India has also worked hard to become self-reliant. New Delhi’s policy approach to enhancing its regional power projection centers on strengthening its domestic sector. New Delhi has pushed for self-reliance through its ‘Make in India’ initiative, aiming to reinvigorate domestic manufacturing and product development, but these interests have borne the brunt of China’s aggression and lack of transparency. In early September, Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar stated that scrutinizing the security of China’s investments should be of utmost concern. New Delhi remains untrusting of Beijing’s international projects, especially in telecommunications, highlighting a continued national security challenge and potentially pushing bilateral ties towards a more chaotic future.

China might be using the border resolution as a chance to increase its presence in South and Southeast Asia, highlighting concerns that Beijing could stretch its economic prowess in southern ports, where it has invested enormously in various sectors, now exceeding the capabilities of the United States. China has become the number one sponsor of port development in the Global South, pouring billions into the establishment of critical maritime infrastructure in the Indian Ocean. China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) lead the financing and construction of ports in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam. In turn, India might have a stronger incentive to counter China in the Global South. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s new 10-point plan, unveiled at the 21st ASEAN-India Summit, promises enhanced connectivity and exemplifies India’s ambition to challenge Beijing in what has become known as the ‘Asian Century.’

The LAC resolution suggests a shifting geopolitical environment in the Himalayas. More importantly, however, the move signifies a broader change in economic and political diplomacy across the Asian continent. While it will take months to calculate the longer term effects of the agreement, the decision to disengage should be seen positively at a time when the bubbles of conflict threaten to burst all over South Asia.

Joshua Bowes is a Non-Resident Research Associate at the Center for Security, Strategy and Policy Research (CSSPR), University of Lahore.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of Pakistan Politico.