Courtesy: AFP

Moeed Yusuf

The Evolving Global Order

The world has moved from its unipolar moment into multipolarity; China has arrived; Russia has resurged; and the era of singular U.S. dominance is over. This is the buzz in Pakistan’s officialdom and the broader policy community. Many are excited at the prospect of being firmly anchored in the Chinese camp. Some also see this as a means of offsetting U.S. pressure and the India-U.S. partnership.

Indeed, the shift in the center of gravity away from the U.S. is undeniable. The trend in terms of China’s economic rise and accelerated military modernization has been clear for some time. China has also begun to show an uncharacteristically high appetite for diplomatic involvement and assertiveness in global conflicts. For many developing countries, the lure of Chinese financial liquidity and its willingness to invest in fragile states is irresistible. Russia, for its part, has made no secret of its interventionist policies to challenge the U.S. in its Eastern European and Central Asian backyards.

And yet, the Pakistani take on the evolving global order needs a rethink. It reflects a Cold War hangover. The bipolar world was all about alliance politics. The neatness of the two superpower camps and Washington’s and Moscow’s obsession with alliance credibility considerations made their and their allies’ behavior rather predictable: they sought to defend their allies in proxy theaters while the allies maneuvered to draw maximum payoffs for their loyalty to their respective patrons. Non-superpowers weren’t free to switch camps at will; the costs of doing so were often too high.

The emerging global order is different in two crucial respects. First, unipolarity is loosening but not disappearing. U.S. competitors are catching up and are able to offer countries attractive incentives to elicit their support on key issues or in specific regions of the world. Overall though, the U.S. military preponderance remains all but absolute, and even “economic, technological, and other wellsprings of national power are concentrated in the United States to a degree never before experienced in the history of the modern system of states” (World Out of Balance: International Relations and the Challenge of American Primacy, 2008). China is the only country with the economic resources to develop power projection capabilities necessary for a superpower, but it gains little by actively subverting the international political and economic order that it greatly depends on and benefits from. While China and Russia are exhibiting increased issue-based cooperation, their own differences are stark. When one parses China-Russia engagement, one finds no broad balancing coalition emerging with the objective of eclipsing the U.S.’s position as the leader of the world. This may change – the events of the last year since U.S. President Donald Trump took office are accentuating tensions – but even if such an effort were to evolve, the power differential between the U.S. and its competitors makes it materially impossible for them to achieve a decisive break from unipolarity for the foreseeable future (Brokered Bargaining in Nuclear Environments: U.S. Crisis Management in South Asia, 2018).

Second, rather than solidifying into hard U.S. versus anti-U.S. camps ala the Cold War – this is the increasingly prevalent view among segments of Pakistan’s officialdom – alliance structures are likely to remain in flux for the foreseeable future. The most successful middle and weak states will be those who are able to make themselves relevant for multiple great powers simultaneously rather than anchoring themselves in one camp in opposition to the other. India, with its burgeoning relationship with the U.S., a lingering partnership with Russia, and a nearly-$100 billion trade with China has already proven so. Indeed, save exceptions, support for allies from the rising great powers is likely to be carefully calibrated. China will be unlikely to do anything for its partners that could risk rupturing its heavily-interdependent relationship with the U.S. To the contrary, it will continue to counsel its partners not to put it in a position where it must confront the U.S. on their behalf. No surprises here; it is only logical for a state for whom more-of-the-same amounts to a constantly narrowing power differential with leader of the world. Also, countries seeking Chinese support may begin to revise their own cost-benefit analyses of being decidedly pro-China. China’s mercantilist model of engagement that often demands preferential treatment and exceptions to domestic legal regulations, lacks focus on institutional strengthening in host countries, and forces an influx of Chinese labor into already-labor surplus countries could entail greater long-term costs than are initially apparent. Concerns about CPEC in some Pakistani quarters are warranted in this regard.

The Dangers of a Willfully Partisan Pakistan

Pakistan is at a crossroads. Misreading these global developments could force it to adopt an unnecessarily partisan foreign policy stance and force the Western world (and India) into outright opposition. This would only make it easier for the most critical Western voices to push for greater Pakistani diplomatic isolation. Paradoxically, as Pakistan’s options for international support narrow, it would weaken Pakistan’s negotiating hand with China while putting China in precisely the situation it wants to avoid vis-à-vis the U.S. (in terms of defending Pakistan’s interests).

There are other reasons that make partisanship a self-defeating proposition for Pakistan. First, the U.S. role as Pakistan’s largest export market, its unparalleled clout over international financial institutions that Pakistan seems set to continue depending on, and the military’s deeply-embedded preference for western hardware together represent one of the major factors determining Pakistan’s economic and military viability. Its importance cannot be overstated.

Second, Beijing has been persistent and explicit in signaling its desire for Pakistan not to allow its ties with the U.S. to rupture. American and Chinese interests vis-à-vis Pakistan diverge on the question of the U.S.-India partnership and India’s potential role as a counterweight to China. But there are far fewer disagreements between them on Afghanistan and Pakistan’s securitized policy approaches to defending its regional interests. Increasingly, China has pulled away from vocalizing support for Pakistan’s ambivalent and defensive stance on the presence of terrorist outfits on its soil. While the U.S. may take this narrative too far for China’s liking, privately Chinese interlocutors are also quick to point to the unsustainability of Pakistan’s selective approach to counterterrorism. From China’s perspective, not only is the presence of militant groups on Pakistan’s soil the most likely reason for a potential U.S.-Pakistan rupture and possible U.S. actions to punish Pakistan thereafter but it is also one reason for the continued tit-for-tat India-Pakistan hostility at the sub-conventional level that Pakistan itself alleges has made CPEC a target of Indian-sponsored subversion.

Third, and most important, partisanship will take away Pakistan’s only realistic opportunity to break out of its current cycle of low economic growth and domestic insecurity, a combination that is leaving Pakistan behind as India, China, and the larger region forge ahead. Data is now indisputable: Pakistan’s differential with India will mirror that of India’s with Sri Lanka in less than two decades if the current growth trajectories remain intact. This projection factors in the CPEC’s injection into Pakistan’s economy.

The alternative – the only one that can change the economic equation favorably and increase Pakistan’s strategic leverage in the region – is for Pakistan to cash in on its geography by turning into a geo-economic hub. This promise has never materialized because geostrategy has always trumped economic means of power projection in the minds of Pakistan’s planners.

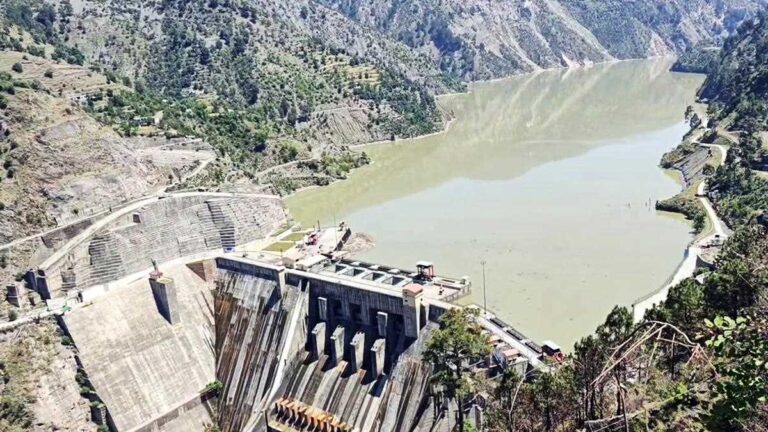

Pakistani leaders must recognize three realities: (i) CPEC’s optimization requires connecting this north-south axis with the lateral east-west one stretching from energy-rich Central Asia to India and further east. The returns from unlocking South Asia are projected to be astronomically higher than in the CPEC-only scenario; (ii) several connectivity projects in and around the region involving India designed to bypass Pakistan are viable only because of Pakistan’s decision to block the east-west axis; and (iii) interdependence between economies creates mutual leverage and can act as an equalizer for weaker parties. This is pertinent to the India-Pakistan dynamic.

Offering up Pakistan as a trade and transit hub for the South and Central Asian region could transform Pakistani territory into a melting pot for great power cooperation. The east-west axis is analogous to the U.S. idea of a ‘new silk road’. Connecting this with CPEC would create natural synergies between the Chinese and American visions for the region. Meanwhile, efforts to involve other western and regional countries in CPEC should make CPEC broader and less threatening to those who currently view it with suspicion. In as much as these initiatives are meant to afford a peace dividend, Afghanistan and Pakistan will gain tremendously as many of the energy projects pass through some of the most restive parts of the two countries, again serving a common U.S. and Chinese interest. Opening land routes for east-west trade also implies that Pakistan will gain access to Central Asia (which Afghanistan blocks right now as retaliation for Pakistan blocking access for Afghanistan to India) while reducing the appeal of the Iranian port of Chahbahar, at least as a competitor to Gwadar and India’s principal access point to Afghanistan and Central Asia. Crucially, millions of Indian citizens in western India would become dependent on energy flowing from Central Asia through Pakistani territory or on the smooth flow of trade in the opposite direction. Traditionally competitive regional and global actors would then develop a genuine stake in each other’s stability. As gains from connectivity grow, regional states may begin to see reason to work jointly to eliminate terrorist groups that may seek to undermine regional connectivity. This has never happened before in South Asia.

The flip side of Pakistan’s geographical locale must also not be ignored. Pakistan sits at the intersection of the three most active nodes of great power competition: Asia Pacific; Middle East; and Afghanistan and Russia’s extended Central Asian backyard. With turbulent borders, deeply competitive relations with several of its immediate and near neighbors, some of whom are active participants in these nodes of competition, and an extremely weak writ in parts of its territory, there is little possibility of Pakistan avoiding the fallout of competition in these theaters if it continues to be seen as an unhelpful/destabilizing force. Posing as a proxy for one or the other great power camp in such a context will only increase the vulnerability to pressure from the opposite camp.

****************************************************************************************

What is proposed here is no less than a paradigm shift in Pakistan’s very approach to global politics. It will require a break from long-entrenched bureaucratic and organizational interests and thought processes that have driven policies thus far. More so, it will take decisive leadership and a coherent vision. The world would also have to play its part in understanding Pakistan’s security predicament and support it as it creates the space to affect this change.

The good news is that Pakistan policy makers recognize that the status quo is no longer tenable. Few, if any, challenge the proposed future. Yet, I find decision makers afraid to take transformative decisions. Corollary: inertia persists, and in fact, at times, the system hunkers down further in defense of continuing what it knows best. This logjam must be broken. For with every passing day, Pakistan is falling further behind its peers. If Pakistani leaders truly want to leave a governable country behind for their upcoming generations, this can’t go on like this.

Moeed W. Yusuf is the Associate Vice President of the Asia Center at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

As usual Moeed has given an excellent analysis & sensible advice. Pakistan has a choice.