Source: Indus Dictum

Anum A. Khan

The June 15, 2020 clash between India and China is fittingly in-line with a famous saying, “Imprudence is a moral failing of sorts, but alas it ranks low as a dreamtime concern”. That morality has little role to play in the scheme of global politics is one of the reasons why states resort to taking actions that border irrationality and recklessness. Those dangerous forays sprout from a desire to achieve grandiose goals. India is no exception, and thus, looks to achieve goals through a mosaic of coercive strategies . It has shown the tendency to reshape the contours of the region by challenging the status quo. Ostensibly, India’s behavior can be ascribed to a permissive environment, provided by the United States, to counter the rise of China.

It is reasonable to argue that, to a degree, India’s regional and global aspirations are in harmony with United States’ bid to challenge and contain China. However, Washington’s efforts to prop up New Delhi against China have seemingly not borne fruit, as evidenced by the ongoing Ladakh standoff. India’s utter lack of resolve has come to the fore, something that raises questions on India’s ability, will, and resolve to confront China at the military, strategic, and economic levels. To offset the effects of its poor performance against China and attract sympathy and support from the right quarters, India is using the bogey of a two-front war.

In this backdrop, the important question that arises is this: does India really have the capacity and the resolve to take on China? An assessment of the Sino-Indo crisis suggests that India lacks both. This does not make for good reading insofar as Washington’s containment of Beijing is concerned, especially in the region. It is noteworthy that the U.S.’ embrace of India is linked to the former prodding and bolstering the latter to become a bulwark against China’s so-called expansionism. With India’s inherent weaknesses thoroughly exposed by China, U.S.’ containment policy has been dealt a severe blow.

Going forward, Washington has to temper expectations of New Delhi. It is untenable for India to risk any kind of conflict with China keeping in mind not only China’s might, but also their economic ties. New Delhi is still well behind China when it comes to military and economic power. Also, India has a large trade deficit vis-à-vis China. For Fiscal year 19-20, trade with China amounted to total of 5% of India’s total exports and 14% of total imports. The conflict between New Delhi and Beijing is least likely to turn into a major military conflagration.

The U.S. seems to have forgotten that India has operationally deployed a major chunk of its military resources against Pakistan. It seems that India has ramped-up both the China bogey and policy of appeasement with China while using all the military strength against Pakistan. India has long been faulted as a counterweight to China. The balance sheet shows that India has had little to offer to the U.S. in terms of countering China.

As of today, India is the weakest link in the Quad Axis (Australia-U.S., Japan and India), as if it is a client state. India’s involvement in the Quad Axis is only to get naval assistance and intelligence sharing for Indian maritime strategy in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). If the need arises, India will not fight a war with China for the Quad even when it is being bolstered to take the key role in the IOR against China. India’s own Indo-Pacific strategy aims at building partnerships to balance China. This is an unviable evasive strategy, one that is at odds with those of its partners.

While India’s aggressive armament has not stifled China, it certainly has become a challenge for South Asian stability. Strategic pundits in New Delhi are trying hard to convert Gulwan crisis into a strategic opportunity to further enhance its conventional edge over its archrival Pakistan. Such a scenario will give India incentives to initiate military misadventure along the Line of Control (LOC) between India and Pakistan. To create a pretext for launching conventional operations under the nuclear umbrella, India can, yet again, stage another Pulwama-like incident.

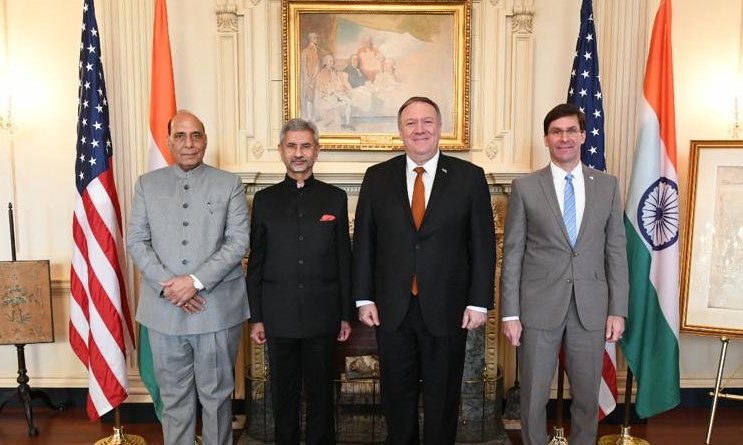

Regardless of the grievous ramifications on strategic stability, Indo-U.S. defence cooperation has been, and will continue to be, the lodestar of wider India-U.S. ties. Most recently, U.S. aerospace giant Lockheed Martin shared information about new partnership opportunities with Indian companies. The cooperation with the Indian industry is in areas like space, aeronautics, Rotary and Mission Systems (RMS), and Missiles and Fire Control (MFC). Interestingly, Indian manufacturing company TATA signed a framework agreement to collaborate in aerospace and defense manufacturing and explore other development opportunities, including that of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). This state of what Stephen Cohen and Sunil Dasgupta called ‘arming without aiming’ will continue in the future as well. This will create a neo-military industrial complex in India, which will fuel long term cross border conflicts.

To sum up, despite constant amelioration of its military infrastructure, India lacks the wherewithal to put up an impressive show vis-à-vis China. The basic aim is to play up the two-front war paranoia, in order to draw U.S’ economic, diplomatic and military support. Washington’s pandering to India will certainly not stop a burgeoning China, but will negatively affect strategic stability in the region.

Anum A Khan-Senior Research Fellow at Strategic Vision Institute (SVI), Islamabad, and a PhD Scholar at Defense and Strategic Studies Department (DSS), Quaid-e-Azam University Islamabad.