Now that the time has come to bury Badaber, it is ironically fitting that no effort to reconstruct its life can be made at Rawalpindi. Its early days are beyond the memory of living men in the Embassy. Its middle years have passed into the misty realms of saga. Even the final period is already en-crusted with legend. And, the Embassy files were destroyed several months ago during the latest of the series of troubles which have affected the deceased’s beloved Pakistan.

Yet, this deficiency is bearable. Countless drawers in Washington and San Antonio cramped with the memorabilia of the day to day life and times of dear departed will ensure Badaber’s place in history. Even more, Badaber will live on in the hearts and minds of all those whose lives were entwined with its own. Well into the Twenty-first Century retired airmen sitting with their children and their children’s children around the glowing barbecue pits of a thousand split levels will begin their tales: “When I first went to Badaber, back in the days when the world was young … ”

It is nevertheless appropriate at a time like this to devote a few moments to recalling what each of US remembers most fondly about Badaber. One may recollect that it answered to many names, accurate and inaccurate: Badaber, USA-60, Peshawar Air Station, USAF Peshawar, “the missile site,” “the U-2 base,” simply “that place.”

To another its charm will remain its association with the great names of history. Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon were all involved in its life. Chairman Khrushchev drew a red circle around it on the map. CHOU EN-LAI, Brezhnev, and Kosygin were not insensitive to its magnetic attraction.

Of lesser luminaries, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto cherished it to the end as a beloved enemy. Its charms entranced Selig Harrison through three incarnations (New Republic, Washington Post, and Brookings Institution.) The Overseas Weekly kept a “death watch” on its final days. To hundreds of anonymous tribesmen its name will ever be mingled in legend with those of Jamrud, Ali Masjid, the Bala Hissar, and the Khyber.

The ever-whirling wheele of Change, the which all mortal things doth sway” – Spenser, The Faerie Queene.

Students of history will mark well the great changes that took place during Badaber’s short life. In the fast moving world of the 1960s of which it was so integral a part, it was a unique witness to the coming of age of the Soviet Union and the birth of Communist China as nuclear and missile powers. It survived the U-2 crisis, and watched calmly from afar the Bay of Pigs and Cuban missile confrontation. It saw dozens of satellites of two nationalities pass over its head; and, in its final days, it beheld man’s first landing on the moon. It stood unscathed through the 1965 Indo-Pakistan War when the sound of bombs falling nearby thundered in its sensitive ears. Afterwards it extended its sheltering arms to receive its small relatives, refugees from the war-stricken Punjab.

Born of John Foster Dulles’ northern tier alliance forged to contain an aggressive Soviet Union, Badaber flourished on the rising tide of U.S.-Pakistani friendship, floated securely through the troubled seas of Pakistani rapprochement with Communist China and the USSR; rode out the tumulus waves of U.S. support for India against China, and in its final days saw President Nixon turn down a Soviet overture for an Asian alliance against Peking.

In Pakistan, Badaber, aloof and unperturbed, observed the rise — and the fall — of Field Marshal Mohammad Ayub Khan. Although it itself always preferred the unadorned name of Badaber, it moved daily among the great Khans: Ayub, Yahya, Asghar, Nur, Rahim of the PAF; Akbar of the ISID. Its name was familiar also to all the gentry of the country from Iskander Mirza to Zulfikar Bhutto.

For many distinguished Americans, too, a meeting with Badaber partook a little of a tryst with destiny. On occasion, DEAN RUSK, Robert McNamara and John McCone together fought for it; other times they fought each other over it. Richard Helms cherished and nurtured it in a very special way, yet courageously signed its death warrant when its fruitful years had come to an end.

Pat Carter, Jack Thomas, Phil Hilbert, Ting Sheldon, Phil Talbot, Luke Battle, and Tom Hughes, together with a score of others burdened with the cares of the world, nevertheless had a special place in their hearts for Badaber; for most of its life they shared its joys and its sorrows. Walter MCCONAUGHY and the USIB spent hundreds Of hours and millions of dollars on it. Gene Locke came to know the intricacies of its towers and cables as intimately and lovingly as he knew the cacti and derricks of Texas. Ben Oehlert, with skill and delicacy, negotiated its complex obsequies.

The brave man carves out his own future, and every man is the son of his own works.” Cervantes, Don Quixote.

It can truly be said of Badaber that it was, above all, a dutiful son.

Badaber devoted all of its rich resources to service of its country. Surely the devotion and selflessness of its men, giving their best on a far frontier, often deprived of family and professional solace, matched anything ever displayed in the Victorian age by the Nicolsons, Warburtons and Cavagnaris. At a critical time in history Badaber strained its senses day and night to acquire the knowledge that so directly protected the very existence of its parent. That it did so successfully is beyond doubt. The GAO alone may one day be able to determine how much family treasure and ingenuity were spent one way rather than another because of the fateful information that Badaber brought home.

To Pakistan too, Badaber never faltered in filial affection. It gave unstintingly of its resources to its poorer neighbors. Barren scraps of land which would never have known the plow blossomed with ripe maize, for the destruction of which compensation could be claimed whenever a cable was laid or an antenna adjusted. Penurious “brass wallahs” were transformed into prosperous burghers. Yet unborn generations of Hayats (furniture makers) will enjoy the benefits of Oxford and Nice because of the favors Badaber bestowed upon their fathers.

Grasping the thorny questions of “participation” and “sharing”, which caused so much anxiety among others of its kind elsewhere in the world, Badaber, quickly and smoothly found a solution which left the ISID and the PAF happier, wiser and richer therefor. Even at the end of its days it bequeathed its earthly home with many of the wonders and riches therein to these beloved companions.

But, as is so often the case, it is only now after its passing that we can truly appreciate that the many lessons we learned from Badaber may be as important as the precious physical gifts we received from it.

Be bold, be bold, and everywhere be bold.” Spenser, The Faerie Queene.

Perhaps the first among these lessons is that at the right time and in the right place the uncertain and the difficult can and should be done. In the mid 1950s it took daring hands to put down an acknowledged U.S. base with a sensitive and secret mission requiring hundreds of politically unsophisticated military personnel and their dependents in a remote area surrounded by millions of volatile tribesmen, to whom the sight of a side of bacon or a bare faced woman was an abomination. It took a gambler’s courage to devise and establish millions of dollars worth of complicated, untried electronic instruments to attempt a task that had never been done before. Even the coolest-minded diplomat might have been forgiven for saying no to a proposal to give so precious and vulnerable a hostage as Badaber to another participant in the game of international politics.

Yet it all worked out: ten years without a major local incident; billions of pieces of unique data collected; security, harmony and cooperation to the end. Such a thing was Badaber and the hands that built it pan take great satisfaction from their achievement. That we are now commemorating Badaber’s end should in no way detract, from this satisfaction.

It is appropriate also for US here, still living, to take humble gratification from the things that we did to, guide and protect Badaber during its life — and the lessons we learned from so doing.

The decision was made early that Badaber should be self-contained, that it should be able to shelter within its own arms the airmen and families that served it and the facilities to make their life tolerable. Many of us who put a premium on people to-people contact and on living as a part of the country in which we serve had doubts about this. We sneered a bit at the rows of ranch houses, the bowling alley, the theater and the golf course. Better that there should be fewer people, inconspicuous, interested in the country and willing to live off it.

Yet this too worked out. The devoted Asian specialists who might have lived off the country would not have known a wavelength from a surfboard. The professionals who did and who came to Badaber found the on-base facilities a substitute for the temptations of Peshawar Town. Nonetheless, over the years, many of them made fast friendships; they brought the “new music” to appreciative young Peshawaris; they were invited to feasts and weddings; they gave to charities; they extended medical aid. And the American image was enriched thereby.

Most of the decisions that affected Badaber’s life and style were wisely made. The diplomats who saw Badaber as an albatross around their necks, an instrument for blackmail which sharply limited the flexibility of our policies, resisted the temptation to cut away the burden Badaber sometimes seemed to be while its value was still high. The information collectors who saw Badaber as a lifesaver that must be preserved at all costs ultimately accepted the judgment that intelligence collection was not the be-all and end-all of U.S. interests in Pakistan.

Nothing in his life became’ him like the leaving it.” Shakespear, Macbeth.

While it is never as satisfying to take apart as it is to build, the hands which devoted themselves to the task of preparing for Badaber’s end were no less skillful than those which built it. They served U.S. — and Badaber’s own —interests no less well. In the early 1960s, when less than half of Badaber’s life was yet run, questions began to be raised as to its future. Ironically, the plans that made Badaber’s death in ripe old age tolerable began to be laid in its youth when its passing would have been catastrophic.

At first reluctantly, convinced that their beloved Badaber would ever be irreplaceable, men and machines began to turn their efforts to seeing what life would be like without it. Then, more vigorously, as the sad reality that all things are mortal was more and more accepted, vast realms of sea and air were probed, obscure corners of the earth examined. Friends all over the globe who scarcely even knew Badaber’s name made their sacrifices to prepare for its passing. When the alternatives were put together at last, often sharing the frailties of those who had devised them, they seemed puny and makeshift compared to the gloriously vibrant integrated organism that was Badaber at its best. Yet, suddenly, it became clear that Badaber, even Badaber, was no longer in its prime. It was not so much that it had deteriorated as that the world around it had changed. The lithe tiger began to resemble just a little a dinosaur. The little improvisations, unglamorous but technically pound, seemed perhaps better suited to the world of the future.

When the word finally came that Badaber must die, there was subdued anger which trembled on the edge of recriminations, but there was also common sorrow and mutual tolerance. As it turned out, Badaber’s friends and relatives had come to be able to face the prospect of life without it and even to devote themselves to working out the dignified and honorable final rites which Badaber so richly deserved. The dying Badaber and its competing heirs worked out together the distribution of its worldly goods. They mourned together and parted friends, free to cooperate once more in the future, should the world change again and common interests reappear. “The tumult and the shouting dies; the Captains and the Kings depart.” Kipling, Recessional.

Badaber is no more. The bowling alleys are silent. The autumn winds from the Khyber hills ruffle the grass where once the little white balls rolled gayly into their holes on the now deserted greens. The great blind dishes ceaselessly turning their sensitive ears to the skies are gone. The drooping wings of the C-l4ls will cast their shadows no more over the shining antennae farms.

Yet the lesson of Badaber’s life is not lost. That free men were able to bring it into being when the world needed it was good but this was not the first time that such a challenge was faced and met. The greater achievement may yet turn out to be that, after it had served, another wide range of skills was brought together to end it peacefully and with honor. The mourners at the graveside and the well-wishers at the christening font have equally important places in the cycle of life. This may be the real lesson from which others of its kind may benefit now and in the future.

Badaber is gone. In life and in death it served a noble purpose. Its spirit and memory will live on amidst the music of the spheres, refreshed alike by the soft chords of angelic harps and the harsh cacophony of electronic blips. We shall not look upon its like again.

SPAIN

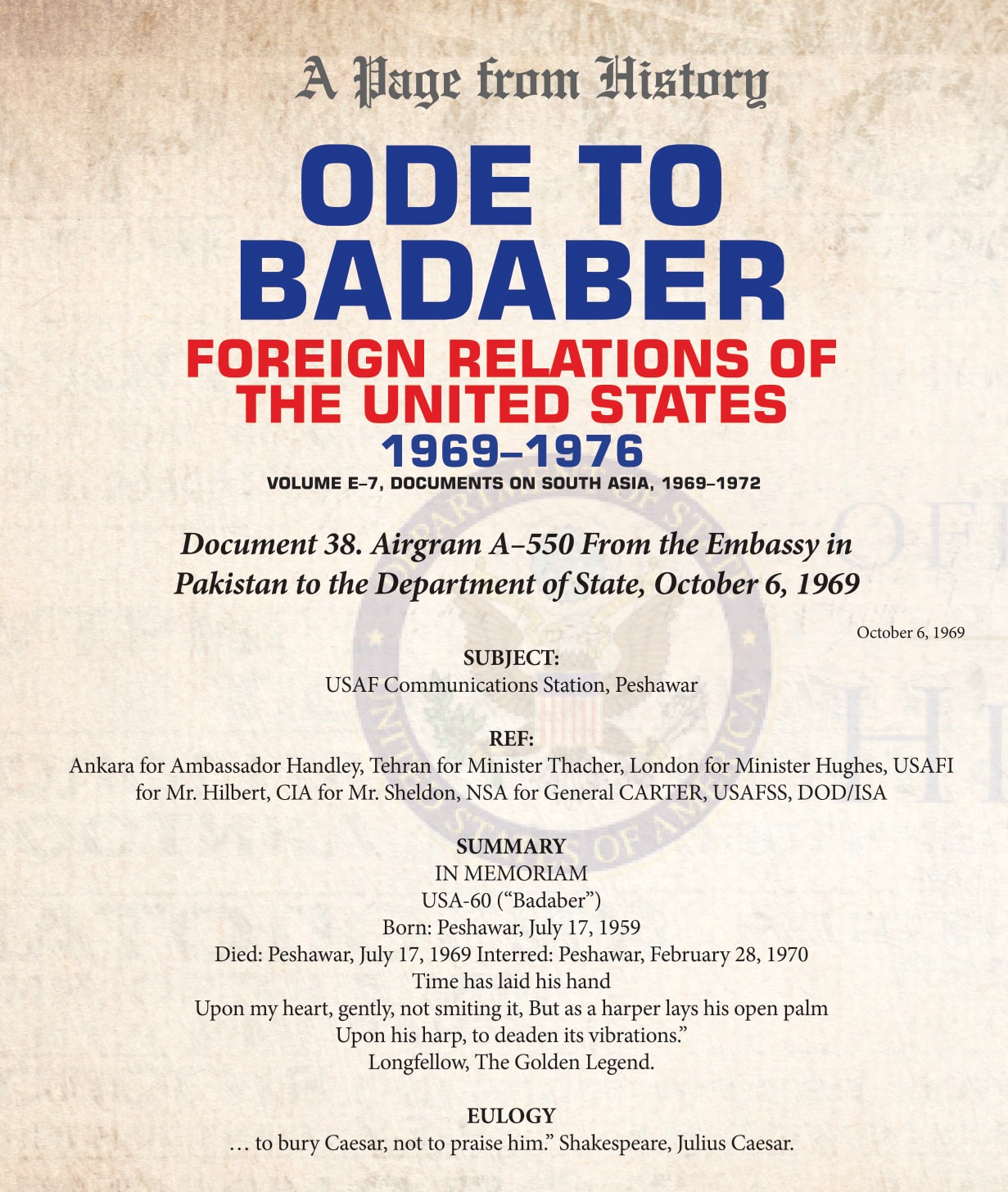

- Source: National Archives, RG 59, Central Files 1967–69, DEF 21 PAK. Secret; Limdis. Drafted by Spain on October 2, and cleared in draft by General Geary and in the political section by Stephen E. Palmer and Alan D. Wolfe. Repeated to New Delhi, Ankara for Handley, Tehran for Minister Thacher, London for Minister Hughes, the Peshawar Air Station for the Commanding Officer, Dacca, Karachi, Lahore, Peshawar, USAFI for Hilbert, CIA for Sheldon, NSA for General CARTER, USAFSS, and DOD/ISA. The 10-year agreement governing the communications facility at Peshawar was not renewed by Pakistan and expired on July 17, 1969. A limited number of U.S. personnel remained after July 17 to effect an orderly turnover of the facility to Pakistan. A brief ceremony effected the turnover on January 7, 1970, rather than on February 28 as anticipated by Spain. (Telegram 001 from Peshawar, January 8, 1970; ibid., DEF 15–10 PAK–US)

- Chargé Spain traced the history and drew the lessons from the experience of the Air Force communications facility at Peshawar.

Spain, James W was the Director of the Office of Pakistan and Afghanistan Affairs, Bureau of Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs, Department of State, January–July 1969; Chargé d’ Affaires in Pakistan, July–November 1969; thereafter Country Director for Pakistan