Andrew Korybko

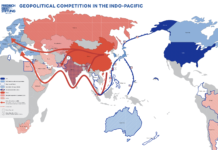

Russia and India’s “global partnership” is tilting the balance of power in Eurasia against China as Moscow opens up doors for New Delhi in the Arctic, Northeast Asia, and Central Asia.

Russia recently came out in partisan support of India over Kashmir, which confirmed the “bait theory” explaining the RussianPakistani rapprochement as of late. It also represented the first time since the end of the old Cold War that Russia openly contradicted China on a serious international issue. Recently, the Indian Ambassador to Russia proclaimed that both Great Powers are “global partners”, which might actually be more than just hyperbole if one takes the time to think about the full geostrategic potential of their bilateral ties. Considering that Russia so openly took India’s side on Kashmir diplomatically “balancing” China, it cannot be discounted that the Eurasian-wide expansion of the Russo-Indian Strategic Partnership might also serve to geo politically and economically “balance” the People’s Republic all across the super continent.

To begin with, Russia’s 21st-century grand strategy envisages the country functioning as the supreme “balancing” force in Eurasia by virtue of its geography and diplomatic capabilities. It enables Moscow to continually adjust the balance of power (specifically in this case between fellow BRICS and SCO members, China and India) in the direction that is most advantageous for it and therefore makes this Great Power indispensable in the New Cold War. Russia’s relatively recent turn towards China was provoked by the Western-backed coup in Ukraine in 2014. Afterwards, Moscow sought to rapidly compensate for its lost economic interests following the imposition of the anti-Russian sanctions by accelerating full spectrum ties with Beijing. While the Russo-Chinese relations are at their highest point in history, they nevertheless are not perfect and have hitherto failed to even approach their real-sector economic potential if one looks beyond arms and resource sales.

There are many reasons for why this is the case, some of which have to do with the worries of Russia’s established domestic economic elite (“oligarchs”) that they might eventually be “replaced”. However, the end result is that much tinier states like Sri Lanka have more successfully integrated with the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) during this same time frame across the intervening half-decade. Russia and China enjoy many strategic complementarities, but there are evidently concerns in the Kremlin about becoming too dependent on its communist neighbor, which is why relations with India have just been reinvigorated after Modi’s latest meeting with Putin at the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok. To be clear, Russia is not “pivoting away” from China or aggressively seeking to “contain” it like the U.S. is trying to do per its so-called “Indo-Pacific” strategy. Moscow sees a longterm benefit in facilitating New Delhi’s rise in Eurasia especially around the Chinese periphery.

Russia’s “Return to South Asia” involves strengthening India’s military capabilities along China’s southern flank through the export of air, naval, and air-defense systems. But if that was the extent of their partnership, then it could merely be dismissed as “balancing” since Moscow sells some of the same military equipment to Beijing like the S-400s. However, there is a lot more to the Russian-Indian Strategic Partnership than just that, as will be argued. Starting with the northernmost vector vis-a-vis China and then proceeding clockwise to end at the westernmost one, Russia has invited India to invest in the extraction of its Arctic energy and mineral resources, which while seemingly benign, will nonetheless lead to a greater Indian presence in the region. That in and of itself is not a cause for concern, except if India instrumentalizes its interests there for military ends by eventually dispatching warships to the area on “port of call” visits in the future, passing through the South China Sea en route to those waters.

Russia and India are seeking to clinch a LEMOA-like military logistics pact that will allow each Great Power to use some of the other’s military facilities on a case-by-case logistical basis, which could enable New Delhi to maintain a semi-permanent/rotating military presence in the Arctic and Northeast Asia (Vladivostok) as well. While likely commenced under the cover of guarding its offshore resource investments and protecting “freedom of navigation” along the Vladivostok-Chennai maritime corridor (which will also eventually extend to the Arctic), the fact of the matter is that the Russian-facilitated expansion of Indian naval activity will lead to New Delhi regularly traversing the South China Sea and sailing up and down the Chinese coast, thus establishing a new precedent (though from the Russian viewpoint, simply mirroring/”balancing” what China is already doing vis-a-vis India in the Afro-Asian [“Indian”] Ocean).

Moving along, the announcement that Russia and India will begin selling their jointly produced supersonic Brahmos missiles to third countries makes it more than possible that Vietnam will be one of their first customers. This Southeast Asian state is engaged in a well-known maritime dispute with China in the South China Sea, and the deployment of Brahmos missiles by its navy might be a regional game-changer. Unknown to most, a subsidiary of Russian state oil company Rosneft is drilling within Vietnamese-controlled waters narrowly located within the southwestern border of China’s nine-dash line. Moscow has an economic interest in “balancing” Beijing there in order to defend its investments. In the event that the Vladivostok-Chennai maritime corridor becomes active, it is likely that Russia and India’s mutual Vietnamese partners will integrate themselves within this developing trade network, possibly even making it part of the joint Indo-Japanese“Asia-Africa Growth Corridor” (AAGC).

The whole eastern maritime component of the Russian-Indian Strategic Partnership – be it Arctic energy extraction, joint naval drills in the Far East, or shared military-strategic interests in Vietnam – could go a long way towards Russia’s de-facto integration into the AAGC. It will be especially so if Moscow and Tokyo finally sign a long-overdue World War II peace treaty (possibly facilitated by New Delhi) that settles the Kuril Islands issue once and for all. It would only be natural for Russian-Indian relations to branch out and include India’s Japanese partners too if New Delhi begins expanding its presence in Russia’s Arctic and Far East regions, especially if this is (at least on the surface) driven by economic motivations. That is not to say that Russia’s possible participation in the AAGC would contradict Putin’s goal of integrating the Eurasian Economic Union with BRI. However, it might make it slow down the pace thereof if China’s competitors offer it better deals instead.

Since South Asia was already accounted for, the final theater where Russia is poised to “balance” China by opening doors for India is Central Asia. Russia has recently

shown renewed interest in the Indian -controlled port of Iran’s Chabahar because of its significance in serving as the terminal point of the North-South Transport Corridor (NSTC). That project’s eastern spoke is expected to expand Indian influence in Afghanistan and Central Asia where China up until now had free rein. Russia is concerned about not being able to break intothe former after the war and being squeezed out of the latter due to China’s dominating economic influence. Therefore, it wants to introduce India as a “balancing” factor since it might be able to compete with it and in process “even the odds” for Moscow. Not only that, India is “comfortably” located far away from Central Asia unlike China, so Russia does not regard the expansion of its economic influence there as ever being threatening to its interests.

Returning to the bigger picture, Russia has clear economic and strategic motives for facilitating the spread of Indian influence all across Eurasia in order to “balance” China. This does not preclude any further cooperation between Russia and China, but to the contrary, might actually reinforce Russia’s geostrategic indispensability by improving its value vis-a-vis both Asian Great Powers and therefore leading to better deals for itself as the two compete with one another for influence with it. Enduring geostrategic interests tie Russia to both China and India, and while each of them might have some contradictory ones relative to the other, the fact remains that Moscow is betting that it can leverage this dynamic to retain its relevance in the 21st century and bring much-needed development to its most far-flung regions. That is not to downplay the risks of this strategy (of which there are many), but just to point out the larger long-term context in which Russian-Indian ties are developing in light of recent events.

Andrew Korybko is a Moscow-based journalist and geopolitical analyst.

DISCLAIMER: The author writes for this publication in a private capacity which is unrepresentative of anyone or any organization except for his own personal views. Nothing written by the author should ever be conflated with the editorial views or official positions of any other media outlet or institution.