Najmuddin A. Shaikh

The month of May this year marked the completion of two decades since India and Pakistan carried out nuclear tests and made the South Asian sub-continent publicly acknowledged as a region with nuclear weapon powers. The 1998 India and Pakistan tests-15 days apart- followed on what India had termed a peaceful nuclear explosion at Pokhran in 1974 and a campaign started in the same year by Pakistan in the United Nations to secure agreement on making South Asia a Nuclear Weapon Free Zone.

It is of course no secret that since the early eighties, the security calculus of both countries was that both had nuclear weapon capability even while there was less clarity about the number of such weapons each side had. Internationally however the 1998 tests led to South Asia being termed a “nuclear flash point”. The existence of this capability was paradoxically also recognized both regionally and internationally as a key element in preventing a repeat of the sort of large scale conflicts between the two countries that had happened in 1948, 1965 and 1971.

Where do the two countries stand now? Both are committed to “minimum deterrence”. This in India’s case has meant creating the triad of weapons ensuring second strike capability, increasing expenditures and research on anti missile defence, a revised nuclear doctrine that permits the use of nuclear weapons if nuclear weapons are used against Indian forces even if these forces are not on Indian soil. The former National Security Adviser, Shivshankar Menon has postulated a disarming counter force strike against Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal which would not violate India’s stated “No First Use” posture.

In Pakistan’s case there is no declared nuclear doctrine. My own rather simplistic view is that the posture of “credible deterrence” now means that Pakistan must maintain a counter value capability which would ensure no Indian Commander in Chief can walk into his Prime Minister’s office and seek approval for a “Cold Start” or other major conventional offensive against Pakistan while offering the assurance that no Pakistani missile would land on the many population centres that are presumably designated targets for Pakistan’s weapons. One element of my thinking on this subject is that, given the short distances involved, today and perhaps for the foreseeable future no technology exists that can enable anti missile defence against missile or cruise missile launches from Pakistan.

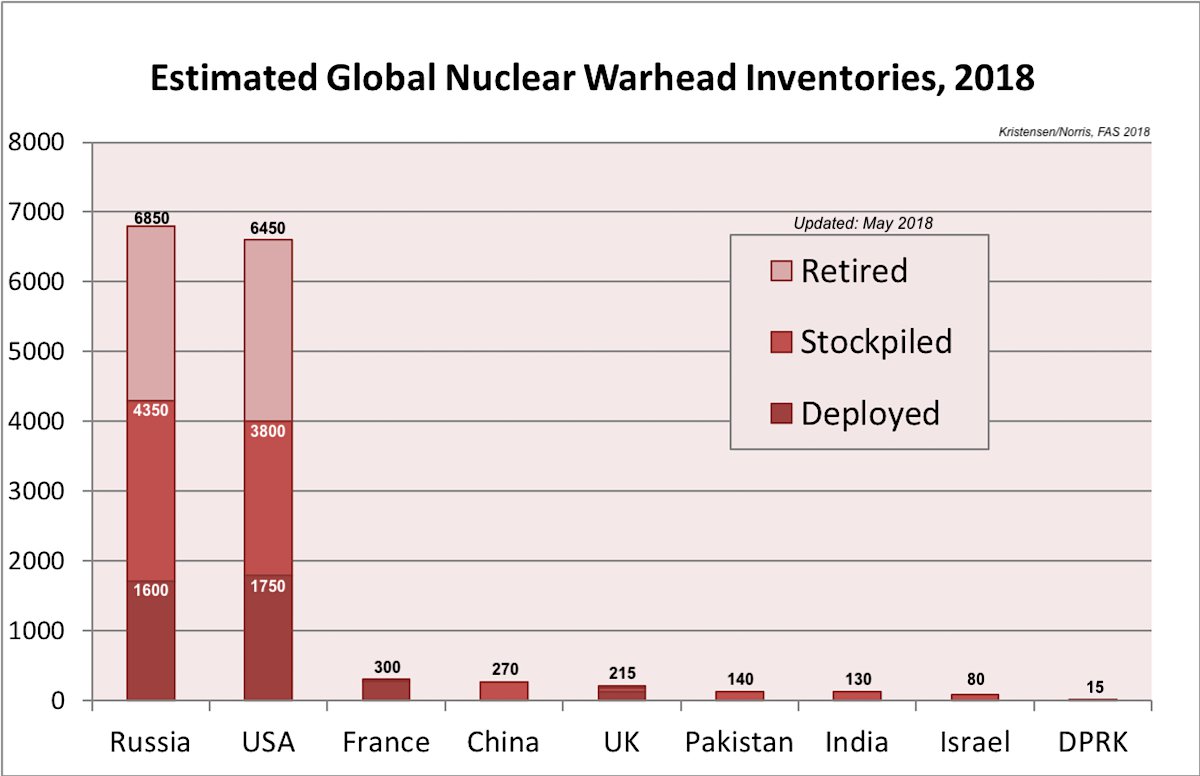

Neither Pakistan nor India have ever disclosed the number of nuclear weapons they hold at their dispersal. American analysts and others suggest that both are growing their arsenals and currently hold between 110 and 130 such weapons (SIPRI estimate of 2014 gives India 90-110 and Pakistan 100-120 while the Arms Control association in the USA suggests that in 2018 Pakistan had 215 such weapons. The recent estimates of the Federation of American Scientists, Pakistan possesses 140 nuclear warheads; the table is appended below.

What at this stage is the international climate with regard to nuclear weapons and their proliferation? Understandably, it could be argued that one must focus on the prospects for JCPOA surviving American renunciation of the agreement and Iran getting sufficient benefits from the other signatories to be persuaded to continue to adhere to the Agreement. Equally one must focus on the prospects for the off again and on again of the proposal for the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula. Both are extremely important and both hold the potential for disrupting what little order there is in a disrupted world.

There are however other developments of which we must take note. This year also marks the 50th Anniversary of the signing of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, a treaty that was put together by the major powers with the specific aim of preventing India from going nuclear. This widely supported treaty, signed by 191 states, codified a ‘grand bargain’ in which the nonnuclear-weapons states promised never to obtain nuclear weapons, the five existing nuclear-weapons states committed to work towards the elimination of their nuclear arsenals, and all NPT signatories pledged to cooperate on the peaceful uses of nuclear energy.

Not only did this treaty fail to prevent the development of nuclear weapon capability by India it also failed to secure the reduction and elimination of nuclear weapons by the five recognized Nuclear Weapon States. Will the frustration of the Non Nuclear Weapon States with the 2020 review of the treaty mean its unraveling?

On 7 July 2017, 122 states adopted the text of a legally binding international treaty that provides for a comprehensive ban on nuclear weapons. The treaty was opened for signature on 20 September 2017, and so far 56 states have signed and five have ratified. The nuclear-weapon states and the NATO member states (excepting the Netherlands) boycotted the multilateral negotiations that produced the ban treaty, something that had never been seen before with respect to a negotiation authorised by the UN General Assembly.

There seem to be no prospects that this brave effort to secure a world free of Nuclear weapons will be any more successful than past efforts that have won Nobel Prize for peace for such organisations as International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (1985), Pugwash (1995), International Atomic Energy Agency and Mohamed ElBaradei (2005),Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (2013), International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (2017).

The Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) put out by the United States and Putin’s speech on 1st March 2018 both make it clear that far from reducing their nuclear weapons or negotiating new arms reduction agreements, the two most heavily armed nuclear powers are intent on introducing new weapon systems along side modernising existing systems. Both have also introduced language which suggests that the trigger for nuclear attack has been liberalised so that as the NPR says nuclear strikes may occur “in response to conventional arms attacks and even to a cyber-threat.” Putin has reiterated the Russian doctrine “the right to use nuclear weapons solely in response to a nuclear attack, or an attack with other weapons of mass destruction against the country or its allies, or an act of aggression against us with the use of conventional weapons that threaten the very existence of the state.”

The new weapons will be both sea based and land based. The American review “affirms the modernization programs initiated during the previous Administration to replace our nuclear ballistic missile submarines, strategic bombers, nuclear air-launched cruise missiles, ICBMs, and associated nuclear command and control”….The United States will maintain the range of flexible nuclear capabilities needed to ensure that nuclear or non-nuclear aggression against the United States, allies, and partners will fail to achieve its objectives and carry with it the credible risk of intolerable consequences for potential adversaries now and in the future.

While the NPR gives many figures to support the contention that the modernization and induction of new weapons is affordable there is no doubt that the defence budget at $716 billion is 130% more that the $295 billion budget that Bush and Gore debated about in the 2000 presidential debate. Many have said that this is being driven by the Military-Industrial-Nuclear Scientific Complex. One observer has described it as “a gigantic bureaucratic complex left over from the Cold War that includes thousands of nuclear scientists in the Los Alamos National Lab, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and Sandia National Laboratories that on a permanent basis try to stay busy in developing, maintaining and building nuclear weapons…. However, most happy are the defence firms that may build the toys. General Dynamics, for instance is estimated to receive $130-270 billion for the construction of the new Columbia-class nuclear submarines. That is a lot of money that will make many people, including politicians, smile.

It is noteworthy that Putin’s proposal in his March 2018 speech, after describing the various new weapon systems that Russia had developed said “let us sit down at the negotiating table and devise together a new and relevant system of international security and sustainable development for human civilisation. We have been saying this all along. All these proposals are still valid. Russia is ready for this.” This received short shrift in commentaries as did the fact that Russian defence budget had been reduced by 20% leaving it in fourth place internationally on defence spending.

Returning to South Asia, one has to see how the global developments recounted above will impact on the region and the nuclear posture of the two countries. There is no doubt that India will continue to claim that its security concerns lie beyond South Asia and will refuse to discuss Pakistan’s proposals for a conventional and strategic arms restraint agreement even if the current impasse ends and a comprehensive dialogue resumes.

How should Pakistan react? Should it be drawn into trying to maintain some sort of balance or should it decide that its ‘full spectrum strategic deterrence’ can be achieved given South Asia’s geography independently of what India does. I believe the latter is the more sensible course to follow.

This will enable us to focus more directly on our battle against terrorism and extremism and on fixing the myriad internal problems that are crying out for more high level attention from all centres of power in Pakistan. An added benefit would be to make us less of a focus of international attention and less inclined to be classified as a country that negotiates by putting a gun to its head.

Najmuddin A. Shaikh is a former Foreign Secretary of Pakistan and Ambassador to USA, Canada, West Germany and Iran.Currently he is the head of the “Global and Regional Studies Centre” at the Institute of Business Management,Karachi.