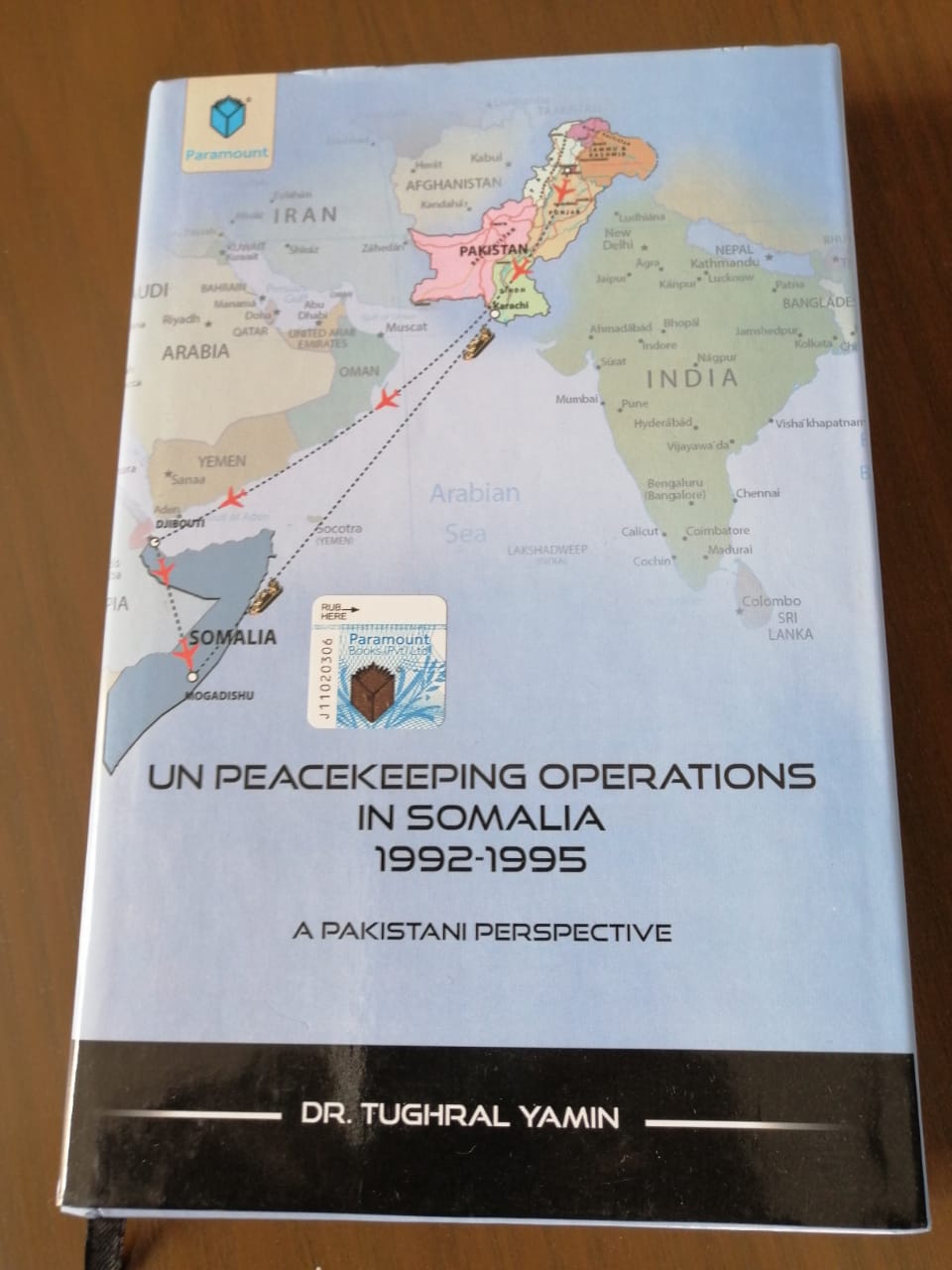

Author : Dr. Tughral Yamin

Publisher: Paramount Books (PVT.) Ltd.

YEAR: 2019

ISBN: 978-969-637-522-7

Ailiya Naqvi

Shouldering a Huge and Dangerous Load for the UN :Assessing Pakistan’s Critical Role in Somalia

“I assure you that any U.S. press report critical of any contingent in this amazing coalition effort is pure fantasy, not fact. We have made that clear in our own reports” wrote Major General Thomas M Montgomery, Deputy Commander of the UN Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM II) in a letter addressed to the Chief of Pakistan Army General Abdul Waheed, after the Battle of Mogadishu in October 1993. “The fact is that many soldiers are alive today because of the willingness and skill of Pakistani soldiers working together with our troops in the most dangerous and difficult combat circumstances … We are very proud to serve at their side.”

The proclaimed acceptance of Pakistan’s vital peacekeeping role by Thomas Montgomery does not cover up his negligence four months earlier, on 5 June 1993, with regard to not informing the Pakistani peacekeepers about the Somali National Alliance (SNA)’s redline that the customary inspection attempt of a weapons storage site in a radio station managed by Farah Aidid’s faction of Somali rebels “would lead to war”. The inability to alert about the impending disaster got 24 Pakistani soldiers killed and 57 injured as the warring militia opened fire on the inspection team, marking the start of a chain of events that resulted in the winding up of the UN Somalia mission in less than two years.

25 years later, a trove of information meticulously pieced together goes on to explain how the extended Somali humanitarian mandate under Chapter VII failed due to lack of clarity, better planning and coordination, and the fractured unity of command. The author, Tughral Yamin, a prominent academician who had served in the same military regiment 7 Frontier Force (7 FF) that was deployed in Somalia, has written a book to underscore the significance of Pakistani peacekeepers to restore stability in the troubled country. The book is the first of its kind in the English language and is a substantial contribution to the discourse on Pakistan’s contributions to UN peacekeeping, a role that has largely been kept under wraps in the literature.

It is a classic study of how intervention in other countries with a maximalist goals-oriented approach is not a good idea. The operation to end starvation for which the peacekeepers were deployed initially (UNOSOM) became an exercise of UNOSOM II inter alia to rebuild the political institutions and re-establish of civil administration, and disarm the warlords. There was a glaring disparity between the aggressive peace enforcement approach envisaged by the UN Secretary General and the logistical, intelligence, and other warfare resources at hand. The command structure in a departure from the standard procedure was also weak as the UN had no operational authority over US forces that were being administered by the CENTCOM Commander in Chief.

Pakistani forces were initially asked to join as guardians of food supplies in Somalia. Apart from this, there were a few other objectives like the protection of seaport and airport, provision of security to the UN personnel and installation et cetera. There was a clarity that altercations with the warlords needed to be avoided and the humanitarian angle of the mission was to be respected. A tense peace prevailed during the earlier months; the situation had become stable enough for the US to get directly involved in Somalia. The UN Security Council Resolution 794 authorised the formation of Unified Task Force (UNITAF), a multinational force spearheaded by the US to use “all necessary means” to establish a secure environment for the relief efforts conducted by UNOSOM. The limited nature of UNITAF and the unwillingness at the part of the US to adopt a more muscular approach towards disarmament resulted in the formation of UNOSOM II under Resolution 814 in March 1993.

After the June 1993 incident, the understanding between Somalis and the peacekeepers became fraught with tension, particularly because the UN had embarked on a personalised manhunt for Aidid and his close associates. In the eagerness to bring the militia leaders down, the house of SNA warlord was bombed at a time when a pre-announced peace meeting including community leaders was taking place. Scores of civilians dead and injured including women and children became a blot on the reputation of the mission in Somalia. The deplorable turn of events on July 12th created an impression that the UNOSOM II was retaliating against all Somalis in South Mogadishu.

To tame the situation, the US Joint Special Operations Command deployed the Task Force Ranger including soldiers from Delta Force and 75th Rangers Regiment, operating outside of UN authorisation to capture SNA leaders. A series of operations codenamed Gothic Serpent were undertaken including the 3rd of October Black HawkDown incident (also known as the Battle of Mogadishu), later adapted into a film. While recounting the incident, Tughral Yamin wrote that planners of the operation used a large potent force of 160 soldiers with air support comprising 19 aircraft in a bid to capture two low-profile lieutenants of Aidid, Omar Salad Elmi and Mohamed Hassan Awale, who were meeting at the Olympic Hotel. The operation which was supposed to last 30 minutes bungled up badly with the loss of two Black Hawk helicopters and consequent capturing of Chief Warrant Officer Michael Durant. The getaway column of infantry men that was to link up with the raiding party inserted from air, was tasked to haul up the captured Somalis (none of whom were close affiliates of Aidid) and the stranded Task Force Ranger back to the headquarters. 90 American soldiers were left in the wild to defend themselves at the end of the day as thousands of Somali militia men closed in.

In the ensuing dark hours, a rescue force drawn up from contingents of Pakistanis, Malaysians and American forces moved out of the assembly area. Only Pakistanis committed their tanks to the operation despite having no night vision capability, whereas there was less enthusiasm from Italy and India, the other two countries with tanks in Somalia. They were assigned to lead the rescue force to the crash site, cordon the area, and provide rear cover to the withdrawing troops ensuring none is left behind. From the amassing of Pakistani troops at the seaport area at 7.05 PM on Sunday evening till 6.30 AM Monday morning, the evacuation efforts took approximately 11 hours to complete,resulting in the deaths of 18 Americans, three Pakistanis and one Malaysian soldier. The realisation by the Americans of their “ill-fated military intervention” parallel to UNOSOM prompted by their naïve reading of events in Somalia led to an instantaneous pull out of their troops from Somalia, which was followed by the withdrawal of other Western and Middle Eastern forces. It was an irresponsible move that created an impression that the US has relinquished the burden of assisting the Africans. A shift in burden of the operation from the West to the Asians was observed, giving it a racial connotation as interpreted by the writer while quoting the then Foreign Minister of Pakistan Sardar Assef Ahmed Ali. This move also left the UN peacekeeping forces with outmoded critical operation resources. A significant percentage of UNOSOM then became very much dependent on Pakistan; around two-thirds of the peacekeeping forces consisted of Pakistanis, Indians and Egyptians.

UNOSOM was a major international exposure for the Pakistani army personnel with respect to peacekeeping operations. They established cordial relations with not just the US soldiers but also Indian, Bangladeshi and Malaysian soldiers. The author in great detail has elaborated on the positive interaction between the Pakistani and Indian contingents particularly, highlighting several occasions where Pakistani forces came to the aid of the Indians. How the Pakistani forces played a role as a mediator between Somali warlords and assisted the Internally Displaced People has also been briefly touched.

Through a comprehensive account painstakingly constructed via primary and secondary sources, Yamin has acutely summarized Pakistan’s accomplishments through UNOSOM as a window of opportunity to get out of international isolation and secure a permanent place in the UN peacekeeping operations. Additionally, the author could have shed much light on the effect of the Pakistani participation on the thought process of the Pakistani military at the strategic and tactical level, resulting in better planning and execution in future peacekeeping missions; leading Pakistan to become one of the top contributors of peacekeeping forces.

Some minor editing errors, primarily pertaining to consistency in dates and punctuation need to be given a thorough check and corrected for the second edition. Overall, the construction of narrative makes for an easy reading and understanding of the perspective on Pakistan’s role in Somalia.

Ailiya Naqvi is Managing Editor, Center for Strategic and Contemporary Research,

(CSCR), Islamabad.