Rabia Akhtar

The nuanced narrative of U.S.-Pakistan relations, particularly regarding Pakistan’s nuclear development, offers a complex interplay between geopolitical strategy and nonproliferation policies. Traditionally framed within a rhetoric of sanctions and restrictions, this relationship warrants a deeper examination of how U.S. foreign policy, while ostensibly aimed at preventing nuclear proliferation, has been tailored to meet broader strategic interests that sometimes conflicted with these goals. If you are looking to read a (free) book on Pakistan’s 26th nuclear anniversary to understand broader Pak-US relations in the nonproliferation context then read The Blind Eye: US Nonproliferation Policy Towards Pakistan from Ford to Clinton. The book seeks to unravel the threads of this intricate relationship, emphasizing the ways in which U.S. policies have, whether directly or indirectly, enabled Pakistan’s nuclear development, and advocates for a significant reassessment of the Pak-US relations narrative in this context.

Historical Context and U.S. Policy Adjustments

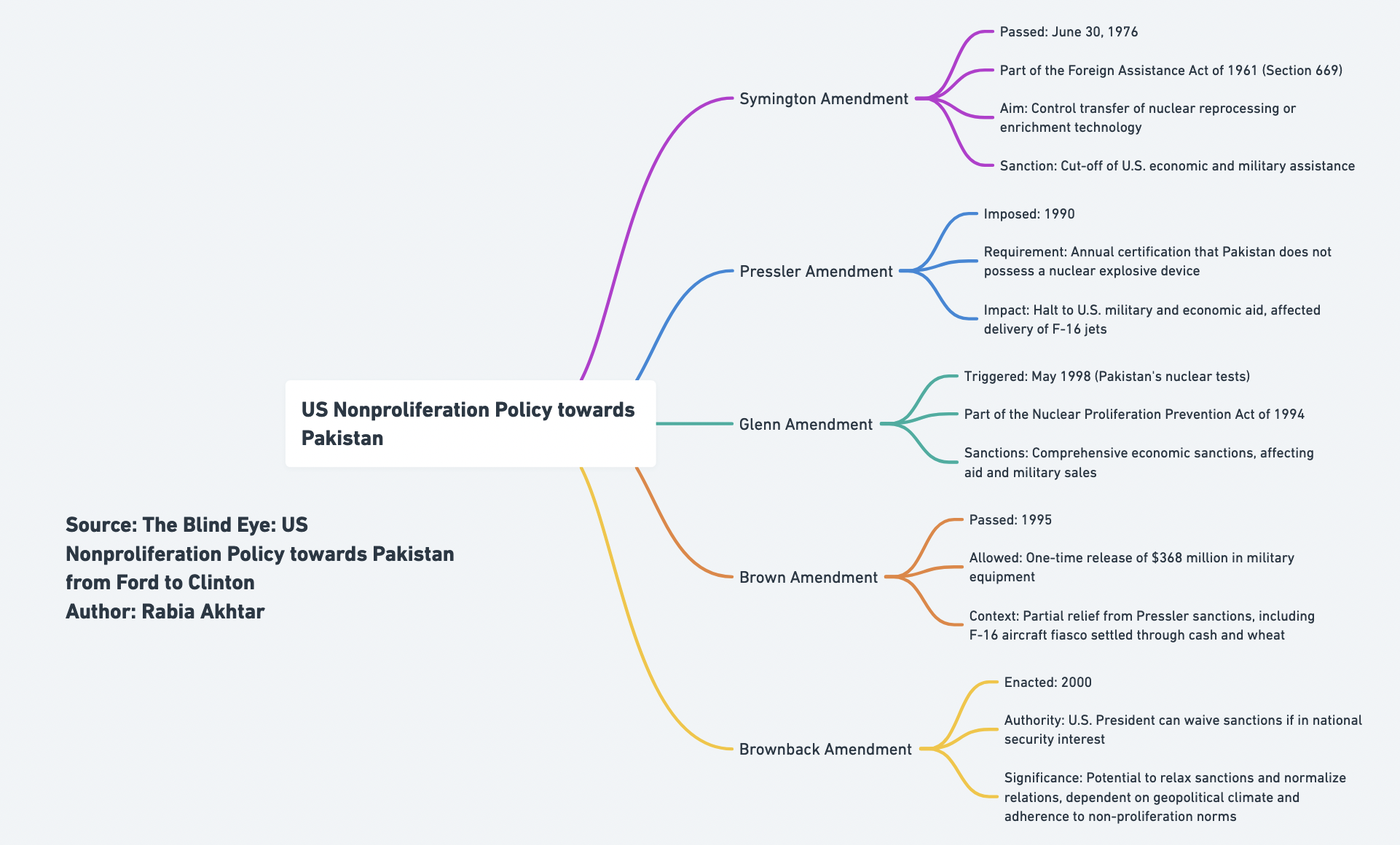

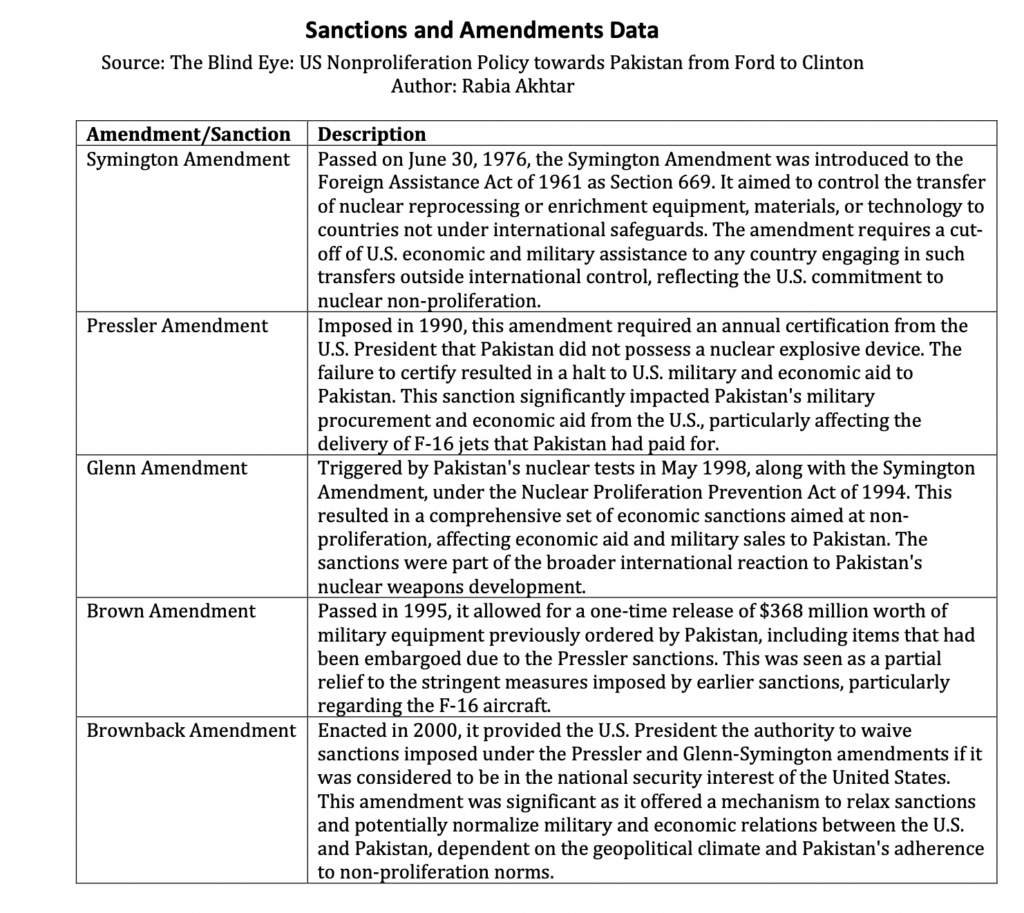

During the Cold War, the geopolitical strategy of the United States was heavily influenced by the containment of Soviet expansion, a motive that often superseded its nonproliferation goals, particularly in South Asia. The Symington Amendment of 1976 was a clear directive against the transfer of nuclear reprocessing or enrichment technologies to countries outside international safeguards. However, despite these regulations, the strategic importance of Pakistan as a counterbalance to Soviet influences in the region often led to a more lenient application of these principles.

The Dual Role of U.S. Sanctions and Waivers

The Pressler Amendment, imposed in 1990, was perhaps the most direct effort by the U.S. to curb Pakistan’s nuclear ambitions by requiring annual certification from the U.S. President that Pakistan did not possess a nuclear explosive device. The failure to certify resulted in significant cuts to military and economic aid. However, the impact of these sanctions was often mitigated by subsequent U.S. policies that seemed to counteract their initial intentions. For instance, the Brown Amendment of 1995 allowed for a one-time release of $368 million worth of military equipment to Pakistan, including previously embargoed F-16 jets, which can be interpreted as a strategic concession during a period of heightened U.S. interests in the region.

Strategic Waivers and Changing Narratives

The enactment of the Brownback Amendment in 2000 underscored a pivotal shift, providing the U.S. President with the authority to waive sanctions imposed under the Pressler and Glenn-Symington amendments if deemed in the national security interest of the United States. This flexibility illustrates how U.S. nonproliferation policies have been intricately tied to its broader geopolitical strategies, often allowing economic and military relations to be adjusted based on the prevailing political climate and U.S. strategic interests.

Pakistan specific US Nonproliferation Sanctions and Amendments Data

Rethinking the Narrative

While the public discourse often revolves around Pakistan’s pursuit of nuclear capabilities as a security dilemma, it is equally important to acknowledge how U.S. policies, through strategic waivers and amendments, have facilitated this pathway, albeit indirectly. This historical perspective suggests a more collaborative and less accusatory approach in future engagements between the two nations.

The intricate dance between sanctions and strategic waivers in U.S.-Pakistan relations, especially regarding nuclear development, underscores a broader theme of pragmatic flexibility over consistent policy application. This pattern is not merely a footnote in the bilateral interactions but a significant driver that has shaped the nuclear landscape of South Asia. The U.S. policy, ostensibly aimed at nonproliferation, has often been adapted to suit immediate strategic interests, reflecting a realpolitik approach in its foreign policy execution.

The narrative that has often painted Pakistan solely as a proliferator needs substantial revision. This is where the narrative needs revision. It should account for how U.S. policies—through various amendments and waivers—have indirectly facilitated Pakistan’s nuclear pathway. These actions were not taken in a vacuum but were deeply influenced by the broader geopolitical dynamics of their times, such as the Cold War pressures and the post-9/11 security concerns.

As we move forward, it is crucial for the discourse on U.S.-Pakistan relations to evolve into a more balanced critique that recognizes the dual roles both nations have played in the nuclear narrative. This nuanced understanding not only provides a clearer picture of past interactions but also offers a framework for future diplomatic engagements. There is a pressing need for a narrative that fosters cooperation, focuses on mutual interests like nuclear safety and regional stability, and encourages a dialogue that transcends the traditional paradigms of sanctions and security threats.

Such a shift could pave the way for more robust, transparent, and constructive interactions between the U.S. and Pakistan, potentially leading to better outcomes in nuclear nonproliferation and regional peace efforts. It is imperative for both policymakers and scholars to champion this revised narrative, ensuring that future engagements are informed by the lessons of the past while aiming for a more stable and secure South Asian region.

Rabia Akhtar is Editor, Pakistan Politico. She is also the Director of the Center for Security, Strategy and Policy Research (CSSPR), at University of Lahore.