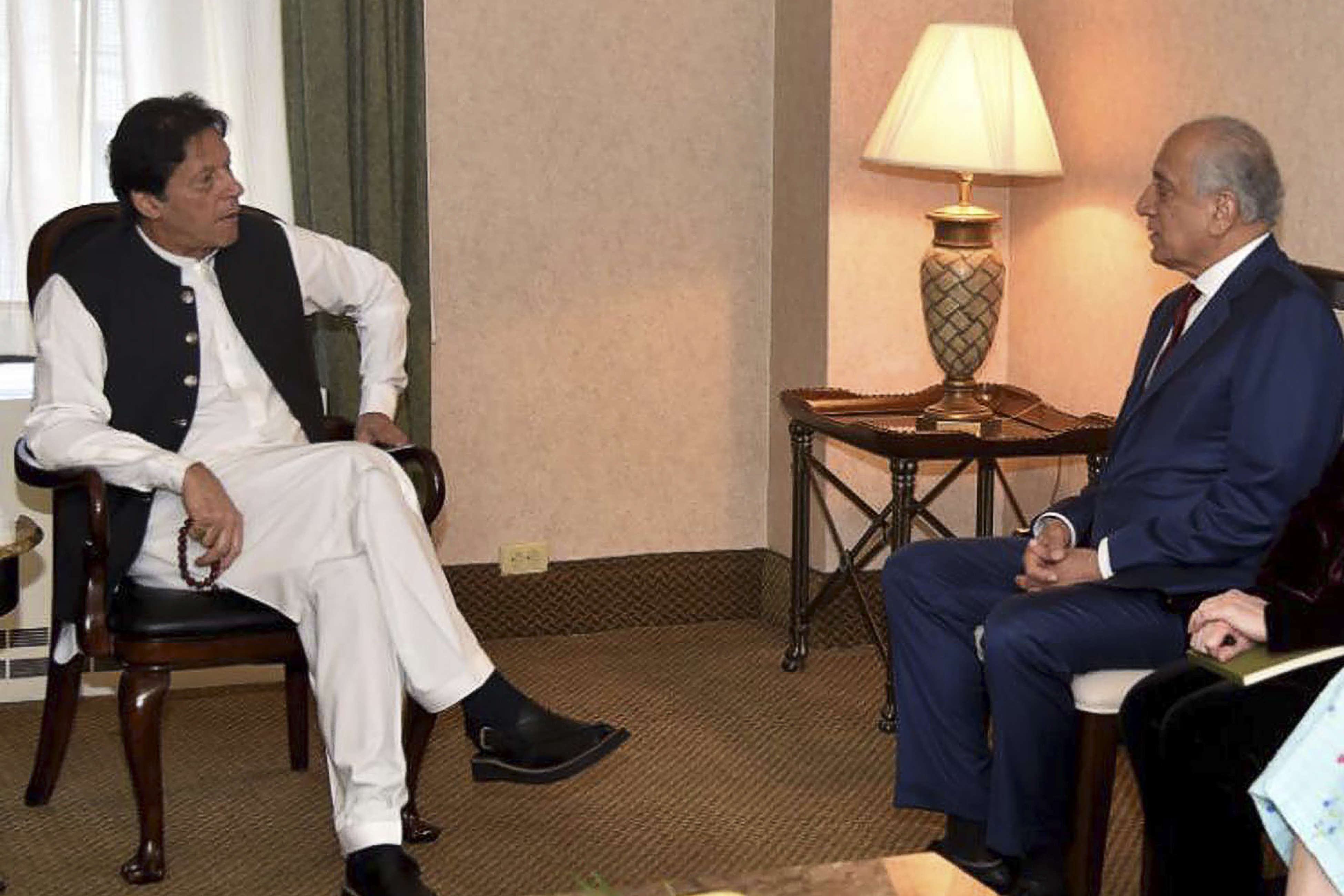

Courtesy: AFP

Qadir Khan Yousafzai

In his customary style, the U.S. President Donald Trump took to Twitter and suspended the Doha peace process between the U.S. and the Afghan Taliban. Despite the fact that the ceasefire had to come into effect after the completion of talks, a Taliban attack in Kabul that killed one U.S. soldier became a pretext for calling off the talks. Suspending the peace process before signing the deal spells more trouble – the war will continue unabated. The intensification of conflict will be a curse for not only the Afghan people but also those elements that were not happy with the Doha process. Nine rounds of talks between the U.S. and Taliban resulted in shaping up a draft agreement. However, the 9th round of talks between Taliban’s Mullah Baradar and U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation, Zalmay Khalilzad ended without a joint declaration. Chances of reaching a dotted line increased manifold when both Khalilzad and Taliban’s spokesman Suhail Shaheen announced that they are on the threshold of signing the accord. Moreover, the draft was shared with the Afghan government. Reportedly, the U.S. agreed to pull out 5,400 troops in a span of 135 days and vacate 5 military bases. The draft reflected that Washington and Taliban had agreed in principle and ironed out their differences.

However, there were spoilers aplenty. Opponents of the Taliban in the Afghan government along with many U.S. lawmakers and Trump administration officials expressed strong reservations about the deal. Concerns regarding what the future holds for the war-torn country were vehemently brought up. A lot of developments were taking place simultaneously: Afghan President Ashraf Ghani postponed his visit to the U.S., Commander U.S. CENTCOM, General McKenzie Jr. led a 17-member delegation to Pakistan, and Pakistan hosted a tri-nation Foreign Ministers’ conference involving Afghanistan and China. The agreement was a tough sell. President Ghani and his government did not buy it one bit. The resistance from Kabul compelled Khalilzad and Gen. Scott Miller to meet the Afghan Taliban again. The draft only needed ratification by President Trump but that did not happen, and instead, talks were cancelled.

As things stand right now, concerns about the future government-making in Afghanistan are more pressing. These apprehensions emanate from the loose ends in the draft agreement. The much-vaunted ceasefire is not guaranteed in the draft agreement. The agreement does not clarify as to whether the Taliban will target Afghan security forces after U.S.’ withdrawal or not. Most importantly, the document does not shed light on what the U.S. would do, should Afghanistan descend into a civil war. Will Washington apply military force or will it just facilitate reconciliation between the Afghan Taliban and other warring factions? Furthermore, the agreement does not specify what the remaining 8,600 U.S. troops will do in Afghanistan. This becomes an important point given that speculations about intelligence and surveillance activities are rife. Fears abound that the U.S.’ intelligence community and private contractors will go for the kill against the Taliban’s leadership. The issue of prisoners’ exchange is also not part of the draft agreement.

If the process does not resuscitate, and if President Trump and the U.S. Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo do not sign the deal, the efforts of Amb. Khalilzad will go down the drain. In case the Doha process restarts, and the deal remains unsigned, there is a possibility that more negotiations will take place in which the Taliban will try to assuage the concerns of President Trump. It is important to note that only after a U.S.-Taliban agreement, intra-Afghan dialogue was to commence in which Afghan representatives were to decide upon a future dispensation for their country. The Afghan Taliban have also time and again said the same.

Though the Taliban are targeting Afghan and U.S. security forces as of now, there is a likelihood of a temporary ceasefire. The Taliban will try to mend fences with small warring and opposition groups. These matters have been in the works on the sidelines. Pakistan, for its part, has reiterated that it does not want to install favorites in Kabul. That said, Islamabad has been unequivocal in putting across its concerns to the U.S. about New Delhi’s role and influence in Kabul.

Despite all this, talks floundered. One of the reasons for this relates to the mandate. While the Taliban’s negotiation team is fully empowered, that of the U.S. is not, for it has to get nods from officials in Washington. Also, though the Afghan government was not part of the Doha process, it was also slated to ratify the agreement between Khalilzad and Mullah Baradar. Amb. Khalilzad wants an agreement on all clauses of the deal. The Americans also want the Taliban and the guarantors to sign the deal in a special ceremony, something that will make it a public extravaganza.

Hopes of a resumption have risen once again. President Trump during his meeting with PM Khan said that the latter wants to help and get something going with the Taliban. This was followed by a major development. The Taliban’s Doha-based negotiation team led by Mullah Baradar came to Pakistan to discuss the peace process. Given that Khalizad and Gen. Miller were also present in Islamabad, the visit was seen as a great stride towards reviving the process. The US and Taliban negotiators indeed met in Islamabad, leaving pundits hopeful of a deal-signing in the near future.

Pakistan has assiduously and quietly facilitated direct talks between the Afghan Taliban and Washington. However, seemingly, Taliban’s continued acquiescence to the tenets of the prospective deal is being dubbed as Islamabad’s responsibility, meaning that if things go wrong, Pakistan could bear the brunt. Insofar as the role of other countries is concerned, Abu Dhabi and Riyadh are playing a quiet and limited role. However, the chances of their backchannel efforts cannot be ruled out, especially after the visit of their foreign ministers to Pakistan. Many countries have possibly played a part in the peace process. Taliban’s guarantors include China, Russia, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates.

One of the oft-repeated questions that pundits try to answer is this: how can the Taliban be pressured when the maximum application of force had failed to turn the tide against the group ? President Trump’s bluster of killing 10 million people is a route that even he himself does not want to take. Anti-Taliban voices can gain traction if the Islamic State (IS) whips up its attacks inside Afghanistan or if human rights issues are brought up in the international media.

Misgivings are leading to more uncertainty in Afghanistan. The situation is being likened to Soviet Union’s withdrawal from Afghanistan. This is primarily being done to link the durability of peace to the presence of U.S. forces in Afghanistan. However, proponents of continued U.S.’ military footprint in Afghanistan ignore that the war has been a burden on U.S. taxpayers, for despite spending trillions of dollars, the U.S. has not achieved its objectives. While the wars in Iraq and Syria have financially benefited the U.S., the war in Afghanistan has been used for extractive purposes and as a bulwark against a burgeoning China.

There are many stages before lasting peace is brought about in Afghanistan. However, it is of utmost importance that talks resume. Trump’s stamp is needed, chances of which rise precipitously given that the Taliban agree on a gradual process of withdrawal instead of a drastic and complete pull-out. This practically leaves less room for the U.S. to reject the draft.

President Trump’s keenness to withdraw from Afghanistan gave impetus to the agreement in Doha. Any bilateral negotiations are based on a give and take formula, meaning that both sides must have given concessions to each other. Besides, the future of bigwigs in President Ghani and Hamid Karzai is contingent upon their getting slices of the cake in the post-withdrawal setup. The Afghan election was conducted largely peacefully. Reports of irregularities and non-verification are coming in. Both, Abdullah Abdullah and Ashraf Ghani have claimed victory ahead of the results. Regardless of which way the winds blow in Kabul, things are looking messier in Afghanistan. Anti-Taliban groups, propelled by the Afghan government and the U.S., are wrongly under the impression that Taliban’s entry into Kabul could be blocked. The Afghan Taliban have proven their war withal against U.S. and NATO forces. After their pull-out, it is unreasonable to expect other groups to pose a formidable challenge to the Taliban. If the Afghan security forces ever use remaining U.S. military compounds to mount attacks on the Taliban, it could be deemed as a breach of the agreement, should it be ratified.

The remaining U.S. soldiers will act as observers but their role could change if Al-Qaeda gains strength on the behest of the Taliban. There are voices that fear the U.S. might again start a war in Afghanistan on an Iraq-like pretext. However, such a war is all but likely to spread into other countries and have grievous ramifications for the region.

The U.S. and the Afghan Taliban were on the cusp of signing a deal, something that had given hopes of ending a brutal war in Afghanistan. There are little differences between the two sides. Pakistan has urged the resumption of dialogue and the Taliban have also hoped that the U.S. will make its way back to the negotiating table. The ball is now in President Trump’s court. Prudence demands that talks resume and the deal finalized. Failure to do so will create a lose-lose situation for all stakeholders, especially the hapless Afghan people.

Qadir Khan Yousafzai is a Columnist at Jehan Publications.