Waqas Iqbal

In February 2019, India and Pakistan engaged in a limited aerial battle marking the Pulwama crisis. But the hype of Pulwama crisis overshadowed another ongoing legal battle between India and Pakistan at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), Jadhav Case (India v. Pakistan). This case is unique in several ways as India and Pakistan both have had a face off at the ICJ four times but it is for the first time that this case is based on non-granting of‘Consular Access’ to an Indian national who was caught red handed from Pakistan’s territory while doing espionage for India. The case also raises questions of interplay between international law, municipal law and international human rights law. Moreover, it also includes the ambiguous nature of international law towards ‘espionage’ and theoretical efficacy of Naturalist v. Positivist debate which remains at the heart of all questions of law. The Jadhav Case (India v. Pakistan) at ICJ appeared as a ‘legal paradox’ which will not only have deep impact on the nature of Pakistan-India relations in the near future but also highlight various unexplored areas of legal research in the sphere of international law.

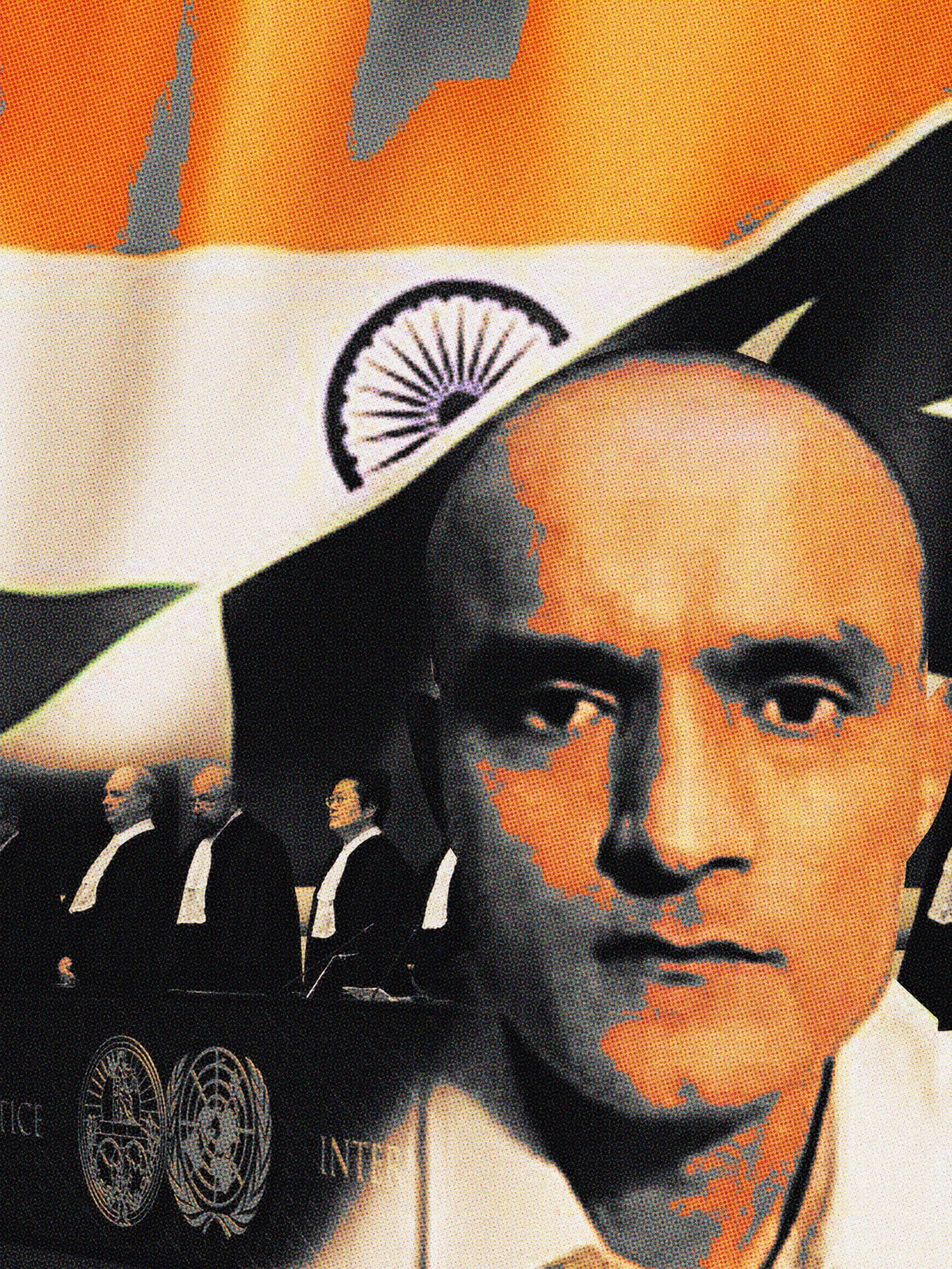

Commander Kulbushan Sudhir Jadhav was arrested from Mashkel area of Balochistan province of Pakistan on 3 March, 2016. He confessed in a video message that he is a serving commissioned officer of the Indian Navy, and his services are handled by the Indian spy agency, RAW (Research & Analysis Wing). Furthermore, he admitted that he was involved in the activities of espionage, sabotage and terrorism in Pakistan especially to disrupt the activities related to CPEC in Balochistan. He was put to trial before the court of Field General Court Martial (FGCM) which found him guilty on offences of spying under Section 3 of the Official Secrets Act 1923, along with Section 59 of Pakistan Army Act, 1952. He had been sentenced to death by the court and the verdict was announced on 10 April 2017. During this time, India forwarded thirteen requests to Pakistan for ‘Consular Access’ to Commander Jadhav. Pakistan refused these requests stating that consular access does not apply in case of ‘spies.’ On May 8, 2017, India approached the ICJ in order to seek relief because of Pakistan’s alleged violation of Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, 1963 (VCCR). According to the press release of the ICJ, India took a different factual position whereby Commander Jadhav was “kidnapped from Iran where he was doing business after retiring from the Indian Navy, and was then shown to have been arrested in Balochistan.”

The President of ICJ wrote a letter to the Prime Minister of Pakistan to halt the execution of Commander Jadhav till ICJ decides the case. On 15 May, 2017 both parties had the first round of public hearing at the ‘Peace Palace’ before ICJ.

After the hearing, ICJ announced provisional measures, time limits and directed both parties to submit memorials and counter memorials for further pleadings. This process of submission of reply and counter reply continued throughout 2018. Finally, on 3rd October, 2018, ICJ announced the date of the second round of public hearing from 18-21 February, 2019. Both parties presented their final arguments before the court. ICJ reserved the verdict and will announce it on the date decided by both the parties.

India’s Claim: from Article 36 (1) to Article 36 (1) (A) and (C)

The Indian application submitted to ICJ on 8 May, 2017 mainly based upon two articles which coincidently have a commonality of title-number i.e. article 36 (1) of the statute

of the ICJ and article 36 (1) (a) and (c) of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, 1963 (VCCR). By indicating article 36 (1) of the statute of ICJ, India justifies that this case comes under the jurisdiction of the world court while reference to article 36 (1) (a) and (c) of VCCR, India maintains that Pakistan committed an egregious breach of the convention. The government of India thereby requested the court to adjudge and declare Pakistan guilty.

Article 36 (1) of the Statute of ICJ

The jurisdiction of the Court comprises all cases which the parties refer to it and all matters specially provided for in the Charter of the United Nations or in treaties and conventions in force.

Article 36 (1) (a) and (c) of VCCR 1963

Communication and contact with nationals of the sending State

With a view to facilitating the exercise of consular functions relating to nationals of the sending State:

(a) Consular officers shall be free to communicate with nationals of the sending State and to have access to them. Nationals of the sending State shall have the same freedom with respect to communication with and access to consular officers of the sending State;

(c) Consular officers shall have the right to visit a national of the sending State who is in prison, custody or detention, to converse and correspond with him and to arrange for his legal representation. They shall also have the right to visit any national of the sending State who is in prison, custody or detention in their district in pursuance of a judgment. Nevertheless, consular officers shall refrain from taking action on behalf of a national who is in prison, custody or detention if he expressly opposes such action.

But the Indian application does not end here. India also seeks suspension of the death sentence awarded to Commander Jadhav through the elementary human rights by referring towards the article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and requested ICJ for the immediate provisional measures under article 41 of the statute of ICJ. India also mentioned article 1 of the Optional Protocol to the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (OP-VCCR) concerning the compulsory settlement of disputes in order to justify its claim that this very case comes under the purview of the ICJ.

Article 1 (OP-VCCR) 1963

Disputes arising out of the interpretation or application of the Convention shall lie within the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice and may accordingly be brought before the Court by an application made by any party to the dispute being a Party to the present Protocol.

It is important to note that both Pakistan and India are parties to VCCR and OPVCCR 1963.

Pakistan’s Defense

Pakistan was summoned by the ICJ in response to the Indian application which stipulates that Pakistan did not fulfill its international obligations under the VCCR and OP-VCCR 1963 and ICCPR 1966. Pakistan reasoned its defense on the following lines:

- India recognizes its national, for whom it sought consular access under VCCR, as Kulbhushan Sudhir Jadhav, an Indiannaval officer. The Indian passport (No. L9630722) which was recovered from Commander Jadhav carried a Muslim name, alias Hussein Mubarak Patel. Pakistan argued against the Indian silence since India did not tell the court that Jadhav’s passport was fake. India also did not produce any evidence that it was not Jadhav’s passport. According to general principles of law, lying to the court is known as the gravest form of contempt of court.

- Pakistan challenged the Indian argument of violation of VCCR on the grounds that Jadhav was doing espionage inside Pakistan which itself is not a violation of article 55 of VCCR and article 2 (1) of the UN Charter and does not fall under the purview of article 36 (1), (a) and (c) of the said convention. Moreover, previous decisions of the ICJ cited by India in its application do not match the facts. For instance, the Indian counsel mentioned more than once, the LaGrand case (Germany v. USA) where ICJ found USA guilty with regard to VCCR article 36 (1) but LaGrand was not charged for espionage, sabotage or terrorism.

- Pakistan also challenged the jurisdiction of the court in this case sought by India under article 36 (1) of the statute of the court where India self-contradicts. On 8th September, 1974, India deposited a reservation to ICJ which had two elements. The first was to exclude from the jurisdiction of the Court any dispute with a Government of a State which has been a member of the Commonwealth. And second, to exclude the jurisdiction of the court, disputes related to the interpretation and application of the multilateral treaties, which the VCCR and OP-VCCR 1963 plainly are, unless all parties to the treaty are also parties to the case before the court at a time when these provisions were already invoked by the court in the case of Aerial Incident of 10 August, 1999 (India v. Pakistan).

The Jadhav case (India v. Pakistan) offers a great deal of legal research. Initially after the first round of public hearing at the ICJ on 15 May, 2017, the court took provisional measures which provided an instant relief to India but in the second round of oral arguments held from 18-19 February, Pakistan made a successful comeback. Theoretically speaking, the Indian plea is based upon the naturalist approach in international law which deals with the spirit of the issue on high moral grounds. India wants to get benefit through invoking international human rights law but its arguments so far have failed to answer the questions related to espionage, a grey area of international law, and terrorism.

Pakistan’s claim is based on the positivist approach, the black letter law that Pakistan

has neither violated article 36 of VCCR nor remained negligent of any of its international legal obligations. In fact, international law is well developed on aggression, territorial integrity and sovereign equality of the states but it is not the case with terrorism and espionage during peacetime. International law is vague in the domains of terrorism and espionage during peacetime since IHL (International Humanitarian Law) provides legal blanket only to wartime espionage. This favors Pakistani position.

India and Pakistan both are dualist states, and require national legislation as far as their international obligations are concerned. Their criminal laws are product of common law. This interplay of municipal law with the international law also favors Pakistan’s claim but apparently, the provisional measures taken by the ICJ reflect bias as it upheld its jurisdiction for which Indian claim is quite weak.

The final decision of ICJ, expected any time this year, will be of enormous significance as it will remove the ambiguity as far as espionage during peacetime is concerned on whether it comes under the purview of VCCR 1963 or not. Additionally, the decision will also clarify which type of jurisdiction will prevail as India has sought two different types of jurisdictions in this case.

Indo-Pak face off at ICJ is not new but the current circumstances are anything but peaceful. This calls for a recourse to Legal Diplomacy’. In fact, all issues between India and Pakistan have a legal characteristic including Kashmir, water issues, Samjotha express incident, Mumbai attacks, Pathankot, Jhadav, Pulwama etc. Hence, law is at the heart of all these conflicting issues between the two nuclear rivals of South Asia. Legal diplomacy, as stressed by Ahmar Bilal Sufi, an eminent international law expert, should be given a chance. Indian verbosity or an ICJ decision in its favor, for that matter, will not turn down the death penalty of Jadhav as desired by India. The possible decision may direct Pakistan for a retrial of Jadhav with ‘Consular Assistance’. Given that military officers are always tried by the military courts like FGCM – it is not something out of the box. Indian general elections are underway in India and the decision of Jadhav case will likely have an impact on the policy of the newly elected Indian government towards Pakistan. Unfortunately, anti Pakistan rhetoric is considered a key to success in elections by Indian political parties. The decision of this case however, will affect the future of India-Pakistan relations. Even though its language is (a)political, it cannot be ignored that the discourse of international law is always interpreted and reiterated politically. It remains to be seen in this particular case.

Waqas Iqbal is a Research Associate at the Center for Security, Strategy and Policy Research, University of Lahore.