Source: Reuters

Michael Kugelman

One month ago, after more than a year of complex and fraught negotiations, the U.S. government and the Taliban signed a landmark agreement. The deal sets out a timeline for a phased U.S. troop withdrawal from Afghanistan. It also obliges the Taliban to take steps against international terrorism on its soil and to launch peace talks through an intra-Afghan dialogue.

The U.S.-Taliban agreement, by paving the way for peace talks, represents the best chance yet to end a nearly 19-year U.S.-led war. However, disputes both within the Afghan government and between Kabul and the Taliban have delayed the launch of the intra-Afghan dialogue.

There is an increasing urgency to begin talks—and not just because the war has achieved macabre new heights (for example, the last few years have witnessed record-level Afghan civilian and security force casualties).

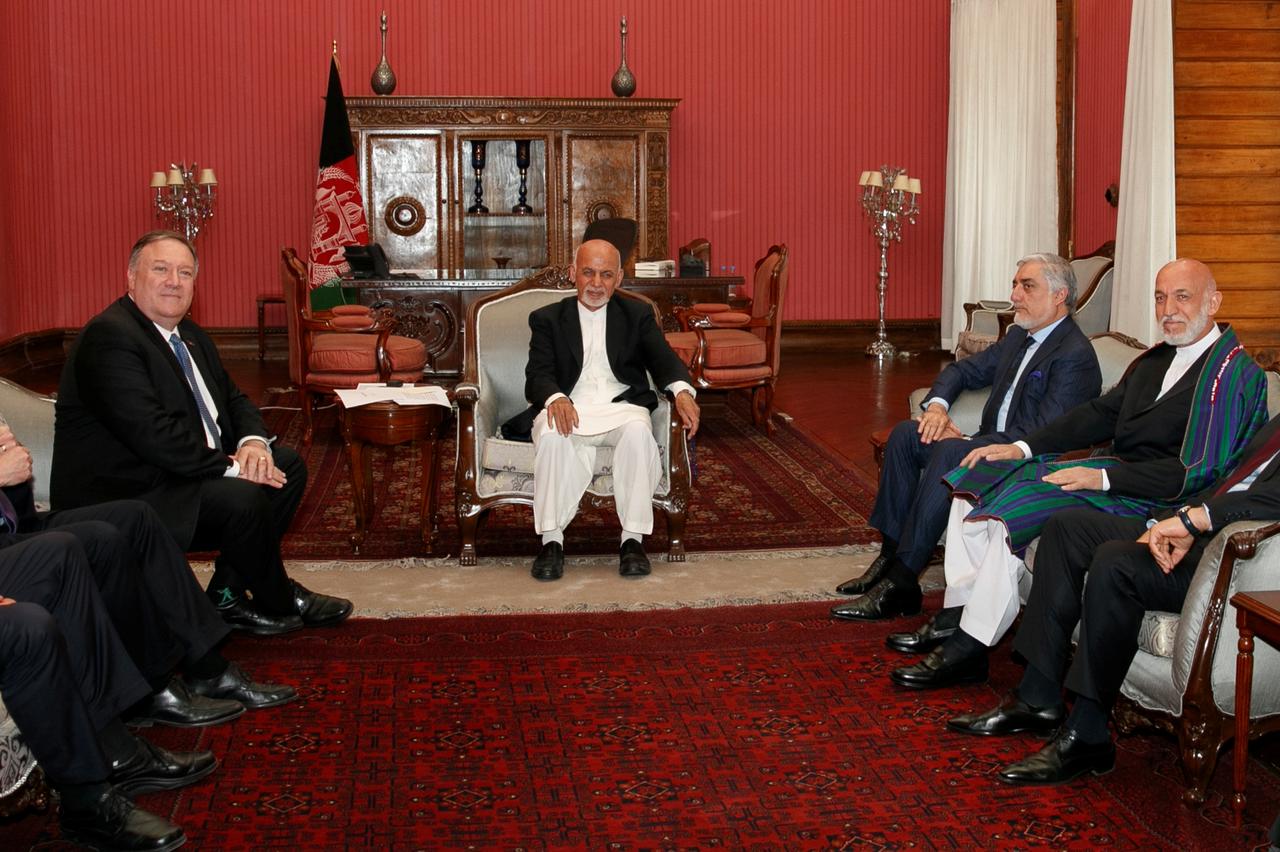

Washington, the most important external stakeholder in the Afghan peace process, is growing increasingly impatient. A frustrated Trump administration announced a $1 billion aid cut for Afghanistan after a surprise visit to Kabul by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo on March 23 failed to end a spat between Afghan president Ashraf Ghani and his main political rival, Abdullah Abdullah—a spat that is a major barrier to launching peace talks. The aid cut—which Pompeo said is potentially reversible—was likely a last-ditch effort to compel the two leaders to end their impasse. But it can also be read as a warning that U.S. cooperation with Afghanistan on peace and reconciliation can no longer be taken for granted.

Additionally, the coronavirus pandemic—which is consuming extensive policy space in Kabul and Washington—could take attention away from peace talks and eventually eliminate any remaining momentum for pursuing them.

The takeaway? There’s an unprecedented window of opportunity for peace in Afghanistan, but that window is in danger of slamming shut. This puts Kabul and its backers in an unenviable position: They must move quickly to address challenges that would take ample time to tackle even in the best of circumstances. And they must endeavor to launch, sustain, and ideally conclude the type of complex peace process that typically takes not weeks or months, but years or even decades.

Gauging prospects for Afghanistan’s peace process is not easy, given the all-encompassing level of uncertainty at play. While the Afghan government has released its proposed list of negotiators for the intra-Afghan dialogue (a list the Taliban promptly rejected), we do not know what it hopes to get out of peace talks, other than an end to war. We do not know what the Taliban want; the insurgents say only that there must be sharia law in any post-war government. We do not know what a political settlement would look like, or what either side would accept, other than a vaguely defined power-sharing arrangement. And we do not know what Washington’s intentions are. What role will it play in peace talks? Will it hold back on withdrawing all troops until there is an actual peace deal? At this point, any semblance of clarity is lacking.

In effect, the core trifecta—Kabul, Washington, and the Taliban—is either keeping its cards close to chest, is utterly unsure of its goals, or a combination of both. And this complicates efforts to make prognostications about the path forward.Against this unsettling backdrop of urgency and uncertainty, three questions can help assess Afghanistan’s peace prospects.

First, can peace talks truly move forward so long as the Afghan government remains divided?

The spat between Ghani and Abdullah may be the greatest obstacle to launching peace talks. It arose in February, after Ghani was declared the winner of the 2019 presidential election. Abdullah rejected the results and declared himself president. He even went so far as to hold his own presidential inauguration on the same day as Ghani’s. In recent days, there has been modest progress in addressing other obstacles, including the finalization of the Afghan government’s list of negotiators for intra-Afghan talks and some movement on a plan to release Taliban prisoners—something the Taliban says must be done before the commencement of peace talks.

And yet, the Ghani-Abdullah dispute remains entrenched—with problematic implications for peace talks. An intra-Afghan dialogue is meant to be politically inclusive, with buy-in not just from Ghani and his supporters but also from powerful opposition leaders like Abdullah. If Ghani and Abdullah—bitter rivals even during the best of times—continue to spar, then the Afghan state will struggle to present a common front and a shared set of goals and expectations at the negotiating table. This will undermine Afghan negotiators’ bargaining position—one already weakened by the fact that the Taliban, which is performing well on the battlefield and controls ample rural territory, has much less urgency to conclude a deal than does Kabul.

Ultimately, peace prospects are enhanced if Ghani and Abdullah agree to bury the hatchet, set aside their grievances, and work together with their respective backers to develop a negotiating strategy for talks with the Taliban. One good sign is that in recent days, Abdullah has endorsed the government’s list of proposed negotiators.

Second, how committed are the Taliban to talks?

For well more than a year, the insurgents’ messaging has been consistent: After we negotiate a troop withdrawal deal with America, we will negotiate a political settlement with our fellow Afghans. The question, however, is if the Taliban’s desire for the latter is as genuine as it is for the former. The insurgents had always been open to talks with Washington, because they wanted to negotiate the withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan. Their incentives for participating in talks with the Afghan state, however, may not be as compelling.

The Taliban have consistently rejected the Afghan political system and vowed to overthrow it by force. Accordingly, would the insurgents truly be interested in participating in a power-sharing arrangement—the most likely outcome of a peace negotiation—within a political system that they have long vowed to destroy?

The best hope in this regard is that the Taliban let practical considerations trump ideological ones. While the insurgents may categorically reject the Afghan state and political system, some Taliban leaders do recognize—as highlighted in a recent International Crisis Group study—that a military victory over the Afghan government, even after a U.S. troop withdrawal, is far from inevitable. In effect, peace prospects are stronger if the Taliban conclude it has a better chance of gaining some power through negotiations than total power through force. And for the insurgents to reach that conclusion, they will need to jettison their longstanding ideologically rooted compulsion to keep fighting.

Third, will there be sufficient international efforts to keep peace talks on track?

Washington pays ample lip service to the idea that an intra-Afghan dialogue, as its name suggests, will be Afghan-led and Afghan-owned. In reality, however, a negotiation this fraught and complex—one that will make the U.S.-Taliban talks look like a walk in the park by comparison—will require external mediation. An outside party or parties will need to be present to frequently impress upon both sides the importance of compromise, and more broadly to offer constant encouragement to keep talking even when the going gets tough.

The question is what individual, nation, or institution, or combination of all three, can serve this role. While the U.S. government is the most logical option, the Trump administration’s strong desire to pull troops and reduce its footprint in Afghanistan undermines its candidacy. Indeed, Laurel Miller, a former acting U.S. special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, stated in a recent online Wilson Center discussion that Washington, instead of pitching itself as a mediator, should help identify others for the job.

The pickings, however, may be slim. There are several potential candidates—such as Pakistan—that may be interested in the role but wouldn’t be accepted by both sides. Then there are those candidates—perhaps a NATO country or China—that may be acceptable to both sides but are not comfortable playing the role. Furthermore, the coronavirus pandemic means that very few external stakeholders will have the bandwidth to serve as mediators for the foreseeable future.

A more realistic option may be external involvement exercised less formally and intensely than it would be in the case of an appointed mediator. A loose and revolving coalition involving Washington, Islamabad, several EU and NATO countries, and a few of the Arab Gulf states could be one potential workable formula.

In the immediate term, however, the core goal for peace efforts should be more modest: Find a way—any way—to initiate the intra-Afghan dialogue. It is critical that the agreement between the U.S. government and the Taliban not have been painstakingly negotiated in vain, and that the unprecedented opportunity for peace generated by that deal not be squandered.

To be sure, starting formal talks is much easier than sustaining them, much less successfully concluding them. Still, that modest milestone would mark an important start, and it would serve as a major confidence-building measure.

Michael Kugelman is deputy director of the Asia Program and senior associate for South Asia at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, DC.