Khalid Banuri

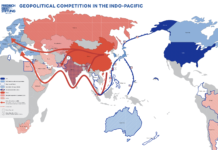

A substantial amount of opinions and reflections has been made in print and electronic media about the incidents that took place in South Asia during the last two months, triggered by the Pulwama attack in the Indian Occupied Kashmir (IOK), in which 40 personnel of Indian para-military force were killed through a suicide bombing by a Kashmiri youth belonging to IOK. As it happens, the fog of opinions not only leaves much to speculation and hearsay, but often shields away some aspects that should be taken by the horn, one of which suggests that the problem is much deeper and entrenched in the past.

While the opinions and analyses would continue evolving, using differing perspectives and offering somewhat diverging assessments, one way to interpret this issue is through an international law lens, while leaving the political positions and associated discussions for another day.

According to the Indian position on the status of Kashmir, IOK is part of India and hence the unrest within it is deemed to be India’s internal security matter. Consequently, India treats the Kashmiri resistance as a problem of internal security and has chosen to come down very hard on it. The structural atrocities committed in IOK on a daily basis have been noticed, among others, by the Office of the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights in its last report. In particular, the use of pellet guns in IOK has led to much consternation, which has killed and blinded several, including women and children. This is thus deemed as a human rights issue that can be dealt under International Human Rights Law (IHRL), which is primarily applicable in peace time.

The Kashmiri resistance views itself as struggling against alien occupation as part of a self- determination movement, which is a legally competent argument in the backdrop of the victimization in Kashmir, as per Protocol I (1977 amendment) of Geneva Conventions. This might explain why they attack uniformed soldiers ostensibly considering them as legitimate combatants under the Geneva Convention. The human angle here thus pertains to International Humanitarian Law (IHL) due to the situation of an armed conflict.

The above notwithstanding, the most egregious violation of international law that occurred in late February this year, was the armed act of aggression committed by India against Pakistani territory through what has come to be known as the Balakot attack.

Simply stated, it is a clear violation of Article 2 (4) of the Charter of the United Nations, which states that “all members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations”.

The Balakot attack occurred inside Pakistan’s territory when India forayed across the international border. It is immaterial that the strike by the IAF could not cause any damage, as the territorial integrity of Pakistan was nevertheless violated through a willful use of force by India. Through this lens, the escalation by India to commit an act of an armed attack, while both sides possess nuclear weapons capability, is an issue of a separate debate, being a grave matter of India’s risk-taking strategic calculus.

India tried to justify its act of aggression against Pakistan by calling it a preemptive non-military strike. This position has two issues- one that preemption does not have an explicit mention in the UN Charter and is notionally controversial; and second that there was no evidence of any imminent attack being planned from Pakistan against which preemption was being claimed. India obviously knew that its strike was a blatant violation of the UN Charter.

It is pertinent, however, to view what actions Pakistan took in this situation when force had already been used against it across the international border, which may explain Pakistan’s response, while being conscious of its international obligations under the UN Charter.

There are only two situations under the UN Charter in which use of force is permissible – first, when a state that has encountered an armed attack against it, then under Article 51 of the Charter, it has “an inherent right of individual or collective self defence….’’; and second, when the UN Security Council itself authorizes a use of force to maintain or restore international peace and security, under the provisions of Chapter VII of the Charter.

Pakistan did the following- which are actions ordained under the Charter. The first action, when the Foreign Minister wrote to the UN Secretary General, was on 18th February, in which the UN was informed of the deteriorating situation, thereby resorting to the provisions of Chapter VI of the Charter that deals with the pacific settlement of disputes. After the flagrant violation by India, on 26thFebruary, the Foreign Minister called the UN Secretary General to apprise him of the aggression committed against Pakistani territory, following it up with another letter. Pakistan thus adopted the legal path till constrained to respond to the attack. Thereafter, next day, Pakistan carried out that resolve through its air operations in IOK. In the ensuing action, an Indian MIG 21 was shot down while it was still inside Azad Kashmir across the Line of Control (LoC), while a second aircraft went down as it flew back to the IOK.

While Pakistan’s actions were perfectly consistent with international law (Article 51 of the UN Charter) while exercising self defence, it ensured that, one, it had reported to the UN about exercise of self defence measures; second, it still did not conduct any attack inside Indian territory and instead took action across the LoC in the disputed territory; third, it adhered to the principle of proportionality and did not conduct any massive operation. An immediate statement thereafter also identified that Pakistan did not want any further escalation. There were reports of subsequent considerations of counter-reactions and counter-counter reactions but that being away from the legal lens, are another debate.

So what does the legal lens tell us about this issue?

- First, the Modi Administration seems to have done something that the earlier Indian Governments may have carefully tried to avoid. Through its use of force in IOK, it could have been argued that Kashmir was a non- international armed conflict, i.e., between India and the Kashmiri resistance movement, because of the nature of the dispute. However, by taking action across the international border inside Pakistani territory, India has turned it into an international armed conflict, with Kashmir in the spot light as the root cause. A permanent solution has to be found now.

- Second, by its resort to aggression and in reference to its captured pilot, who was subsequently returned by Pakistan as a goodwill and de-escalatory step, the applicability of Geneva Conventions 1949 became relevant.

- Third, despite India’s non-signatory status of the Protocols Additional to Geneva Conventions, Protocol I of the Geneva Convention 1949, becomes relevant as Customary International Law.

- Fourth, it may be noted that Protocol I (1977) of the Geneva Conventions 1949, while describing protection of victims, identifies three situations of armed conflicts where people are fighting against- colonial domination, alien occupation, or racist regimes. This in turn strengthens the Kashmiri resistance’s argument regarding Indian “occupation”.

- Fifth, while the notion of self- determination is still stuck in a definitional debate, the issue could potentially re-enter the contemporary international debate.

- Sixth, an armed conflict situation has relevance to International Humanitarian Law (IHL), which again is relevant to international armed conflicts.

An important take away from this debate suggests that the role and reaction of the UN apparatus during the last two months has certainly been less than ideal.

This is manifested in the inaction at the UN level with respect to the provisions of Chapter 6 of the Charter that deal with finding ways for a pacific settlement of disputes between UN members. Later, while the UN was informed of Pakistan’s position on the exercise of self defence measures, the UN had the responsibility to work towards restoration of international peace and security – that should have resulted in a UN Security Council resolution, condemning the use of force by India over Pakistani territory, so as to assist and sustain the de-escalatory intent expressed individually by the parties.

In the final analysis, in the interest of international peace and security, any neglect by the international community at large, but more specifically by the UN itself, is untenable and amounts to ignoring the simmering problem of Kashmir, which needs to be fast-tracked into an open UN debate on priority basis, lest another trigger comes into play.

Khalid Banuri is a former fast jet pilot of the PAF, with experience on F-16, Mirage, and the F7Ps. He was the first Director General of Arms Control & Disarmament Affairs Branch (2012-17) at Strategic Plans Division (SPD). He currently teaches ‘Use of Force and International Law’ at Quaid e Azam University Islamabad. The views expressed herein are his own.