Syed Rifaat Hussain

Stability is a contested intellectual construct with no consensus on its precise meaning. As noted by Patrick A. McCarthy, “it is overly simplistic and, more than that, inaccurate to label a changing system unstable or to label an unchanging system stable.”

What is stability in the nuclear context? In broad terms nuclear stability refers to all those factors or conditions that work to ensure against the breakdown of nuclear deterrence. Henry A. Kissinger has defined strategic stability as a condition “that requires maintaining strategic forces of sufficient size and composition that a first strike cannot reduce retaliation to a level acceptable to the aggressor…. We need a sufficient number of weapons to pose a threat to what potential aggressors value under every conceivable circumstance. We should avoid strategic analysis by mirror-imaging.”

Deterrence stability is crucial to war prevention between nuclear adversaries. As pointed out by Thomas Schelling and Morton Halperin, “A balance of deterrence – a situation in which the incentives on both sides to initiate war are outweighed by the disincentives – is stable when it is reasonably secure against shocks, alarms and perturbations. That is, it is stable when political events, internal or external to the countries involved, technological change, accidents, false alarms, misunderstandings, crises, limited wars, or changes in the intelligence available to both sides, are unlikely to disturb the incentives sufficiently to make deterrence fail.”

South Asia’s passage to overt nuclearization in 1998 has led to the formation of “two camps of deterrence theorists…over whether a nuclearized subcontinent will prevent a major conflict and foster escalation.” These two camps might be called deterrence optimists and deterrence pessimists. Deterrence optimists maintain that nuclear weapons by making war catastrophically costly generate incentives for war avoidance between nuclear rivals and therefore create stability between them. Deterrence optimists have put forth the nuclear peace thesis which states that wars between nuclear-armed nation-states will be unlikely to start, and, if they do, the conflicts are likely to be limited because the belligerents will stop fighting short of the intensity needed to bring about the resort to nuclear weapons.

Deterrence pessimists argue that notwithstanding their enormous destructive potential, nuclear weapons fail to produce stability because of a range of political, technical and organizational factors. Some of the specific problems that trump stability between nuclear states include risk acceptant or irrational leaders, command-and-control difficulties, and preemption incentives for small arsenals.

Scott Sagan has argued that “India and Pakistan face a dangerous nuclear future…. imperfect human inside imperfect organizations…will someday fail to produce secure nuclear deterrence.” Concurring with Sagan, P.R. Chari states that South Asian proliferation undermines a “widely held, a priori belief…that nuclear weapons states do not go to war against each other.” In the same vein, Michael Krepon, a self-proclaimed deterrence pessimist, has identified a number of “conditions” that tend to undermine processes of escalation control and stability of nuclear deterrence between India and Pakistan. These destabilizing factors include: “uncertainties associated with the nuclear equation” between India and Pakistan, “India’s vulnerability associated with command and control”, Pakistan’s “nightmare scenario of preemption” due to India’s “move toward a ready arsenal”, the shifting of the “conventional military balance in India’s favor,”, “the absence of nuclear risk reduction measures on the subcontinent”, the tendency by both governments to “resort to brinkmanship over Kashmir,” “the juxtaposition of India’s nuclear doctrine of massive retaliation with a conventional war-fighting doctrine focusing on limited war”.

Michael Ryan Kraig has highlighted the following drivers of nuclear instability between India and Pakistan:

- The dangers created by geographical proximity between India and Pakistan and India, in contrast to the Cold War, in which the US and Soviets had political-strategic but not territorial proximity to each other;

- The lack of stable boundaries, or at least of stable, tacit agreements on defacto boundaries where disputes about territory still exist;

- The presence of ethno-religious cleavages which are integral to the two state’s founding national identities, in contrast to the more abstract Cold War divisions that were based upon broad political-economic philosophies;

- The existence of violent internal exigencies, which are connected to the above three situational factors and which are also persistently linked to the overarching state-level strategic threats between the two countries;

- The persistent lack of feasible and reliable early warning sensors (due in part to technological barriers and in part to geographic proximity;

- The lack of reliable nuclear safety and warhead access devices (such as Permissive Action Links that ensure only authorized personnel can arm or launch weapons and environmental sensors that will allow detonation only when the warhead is actually at its target); and

- The relative absence of dedicated command and control architectures that allow reliable civilian control during heightened tensions (an absence that is connected to the above factors of nuclear access devices and early warning systems).”

After comparing the East-West Cold War model of deterrence stability with India-Pakistan deterrent relationship, Michael Quinlin concludes that “Overall, the underpinnings of war-preventing stability seems less solid than they had become in at least the later years of East-West confrontation…. the “risks look higher than in the East-West confrontation, both in the political dimension (above all because of Kashmir) and in the military one, because of close proximity and the long-time scale and heavy costs, if operational deployment does go ahead, of reaching the standards of control, invulnerability and safety eventually reached – after much learning and expense – during the Cold War.”

He goes on to observe that “unless one side or other grossly neglects prudent defensive dispositions, neither temptations nor ‘use-or-lose’ fears need be plausible.” To ensure crisis-stability, Michael Quinlin, recommends “if deployment is to proceed at all, neither country should stop at a very low level (for example in single figures) because of risks to crisis stability and confidence if there are perceptions of severe vulnerability and so of pre-emptive danger or opportunity. In addition, an armoury so small as plainly to offer only a single strike option may be bad both for credibility an for proper focus upon war termination, if grave conflict does break out.”

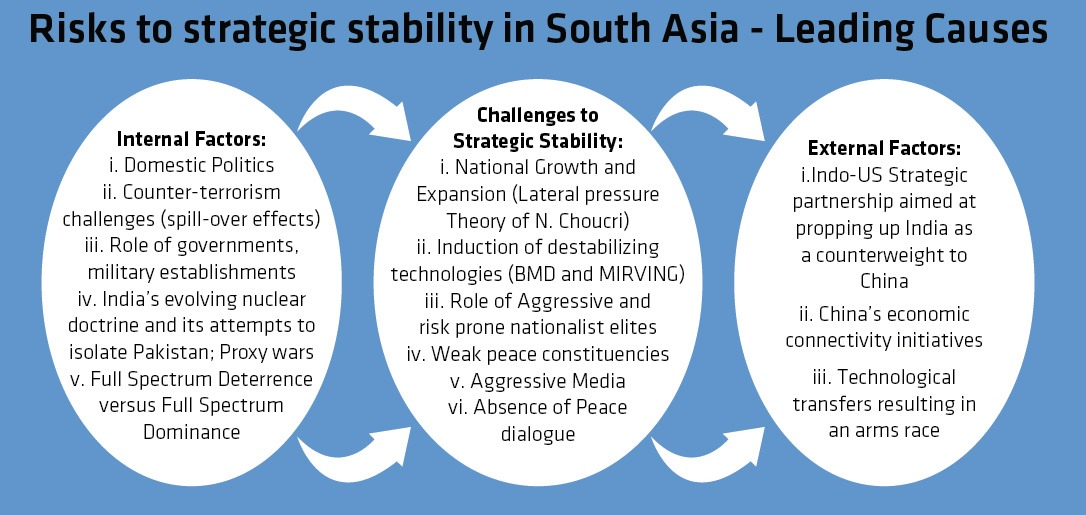

As the foregoing discussion of different views of scholarly opinion suggests that India-Pakistan nuclear deterrence equation, while seemingly stable, is liable to experience severe jolts on account of their enduring rivalry, changing patterns of regional alignments and changing interests of extra-regional powers. A mix of global, regional and domestic trends in domestic politics of each of the two nuclear armed states that would negatively impact on South Asian strategic stability is presented in the following table.

A cursory glance at the above table would reveal that South Asia is undergoing a remarkable structural change that would ultimately lead to a power shift in favor of India as a dominant power.

Ever since the advent to power of the Modi government in India in 2014, India’s domestic environment has undergone a radical rightward shift. As part of its aggressive pursuit of Hindutva, Modi government has consciously cultivated forces of Hindu extremism and has provided them the space to carry out their violent campaigns against minorities including Muslims, Christians and others. As a consequence, civic space has drastically shrunk and India today has become the most intolerant society. The 2017 World Press Freedom Index of Reporters without Borders (RSF), “ranked India 136th out of 180 countries, and it “placed below Afghanistan, Palestine, and Myanmar”.

The ADRN in its March 2018 on Civic Space in Asia concluded:

“In recent years…there has been pushback against the progress made in terms civic engagement…the authorities have used repressive laws to curb freedom of expression and silence critics. Human right defenders and organizations continue to face harassment and intimidation, and vigilante cow protection groups have carried out several attacks. Thousands have protested again discrimination and violence faced by minorities.”

This domestic trend toward violent extremism has been accompanied by state-sanctioned “hate” campaigns against Pakistan in which Islamabad has been painted as the “poster child” of “Jihadi terrorist” violence in India.

To punish Pakistan, India claimed in 2016 that it had successfully waged “surgical strikes” along Line of Control in the disputed territory of Kashmir. These outlandish Indian claims have been met with disbelief by rational circles in India and have been vehemently denied by Pakistan.

Simultaneously, India has been working on the theory of full-spectrum dominance. India is now developing conventional war-fighting options to dominate all rungs of the escalation ladder including limited nuclear use options. This evolving Indian strategy is fraught with dangerous consequences. As noted by Montgomery and Edelman:

“…a competition for escalation dominance is now taking place in South Asia. This has at least two worrisome implications. First, the likelihood of a regional nuclear conflict could increase sharply. India, for example, might conclude that it can invade Pakistan without inciting nuclear retaliation, while Pakistan might believe that it can use nuclear weapons without triggering a nuclear exchange…Second, this competition could be the catalyst for a major expansion of India’s nuclear weapon program, including the development of its own limited nuclear use options.”

In this attempt for escalation dominance vis-à-vis Pakistan, India is relying on its strategic partnership with Washington, which is worried about the rise of China. In the post-September 11 world, drastic modifications were made in the framework of Indo-US engagement: “a number of sanctions imposed earlier were removed; the door for high-tech cooperation was opened; political support was granted to India’s own war on terrorism; the Kashmir issue was reconsidered with a positive tilt towards India.” In 2005 a 10-year Defence Pact was signed followed by an Indo-US nuclear agreement, described by Aston Carter as openly acknowledging India as a “legitimate nuclear power.” Since then India and US have broadened and deepened the scope of their defence cooperation. At present, India is among the top-10 military spending countries in the world. During 2006-2010, it accounted for 9 per cent of all global arms imports, making it the world’s largest weapon importer. New Delhi’s strategic modernization drive and its huge arms-build up is widening the gap in conventional military capabilities between India and Pakistan and forcing Islamabad to rely more and more on its nuclear option to offset India’s conventional force advantage.

The current high economic growth of 7% or more displayed by India should be a source of concern to its entire neighborhood because a significant portion of new Indian wealth is being spent on Indian defense and not on social needs of the people. As suggested by Nazli Choucri and Robert C. North in their seminal study, Nations in Conflict: National Growth And International Violence (1975), “Growth can be a lethal process…. a growing state tends to expand its activities and interests outward – colliding with the sphere of interest with other states – and find itself embroiled in international conflict, crises, and wars that, at least initially, may not have been sought or even contemplated. The more a state grows, and thus the greater its capabilities, the more likely it is to follow such as tendency.” They posit that economic growth and expansion lead to conflict of interest which lead to higher demand for military capabilities and alliances as a means to augment a nation’s military capabilities which ultimately results in “violent action directed toward all other nations.”

Washington under Trump has enthusiastically accepted India as its strategic partner and both are working closely to contain China. Both Washington and New Delhi are opposed to China’s advocacy of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that they see as offering Beijing a historic opportunity to win “hundred years marathon race” against them. As a declining hegemonic power, USA is desperately searching for regional allies to shore up its crumbling empire.

New Delhi is playing a smart game of maintaining economic and trade links with Beijing while tapping into technological resources of the U.S through its strategic partnership with Washington. Because of its strategic geography, its important demography and its strategic alliance with China, Islamabad cannot easily be outsmarted by India, however. Ultimately India and Pakistan, as nuclear armed neighbors, would have to revert to a process of dialogue between them to sort out their difficulties. This is necessary to not let the violent non-state actors hold the reconciliation process hostage to the pursuit of their private agendas. A good starting point would be the revival of the stalled India-Pakistan peace dialogue with a focus on resolving the core Kashmir dispute.

Dr. Rifaat Hussain is a Professor of Government and Public Policy at the National University of Science and Technology, Islamabad.

[…] and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities, missile defense, and nuclear submarines—may tilt the strategic balance in India’s favor. In combination, these systems are a potent weapon for preemption. Thus, […]

Comments are closed.