Salma Shaheen

The notion of responsibility is the new black in the emerging nuclear world order that predominantly aims at reducing nuclear arsenal and minimizing their salience in security policies leading to nuclear disarmament. These aims tend to present the idea of responsibility as abstract and distinct from the realities of prevailing security environment in South Asia whose management rests upon nuclear deterrence – a duo of threat of use of force and state of mutual vulnerability. Therefore, there is a need to appraise responsibility in line with nuclear deterrence where the aim should be to manage mutual vulnerabilities effectively enough to minimize the probability of deterrence failure. In so doing, the nuclear planners tend to aim at establishing and maintaining the conditions (in terms of doctrine and capability) necessary for deterrence to prevent war.

Nuclear deterrence involves threat of nuclear attack to persuade an adversary from taking a certain course of action. In so doing, the nuclear force needs to be capable and credible enough to threaten use of force to inflict desired unacceptable damage in a timely manner. Credibility of this tragic necessity of use of nuclear force is enhanced when unitary and rational nuclear adversaries are in a state of mutual vulnerability. Mutual vulnerability induces fear of retaliation, hence convinces rational leaders to avoid risk-taking. The nuclear adversaries are dependent because being vulnerable is in the interest of both. On the other hand, responsibility, by definition, refers to a state of having a duty to deal with a situation or have a control over something for which one can be held accountable. In nuclear deterrence parlance, it is the responsibility of rational nuclear planners in nuclear weapon states to maintain a credible and effective nuclear posture that sustains the state of mutual vulnerability and related dependency so that deterrence should not be undermined.

Considering the intensity of hostilities between India and Pakistan and competitive arms build-up, it is understood that nuclear weapons continue to exist in South Asia for any foreseeable future. Hence, there lies considerable responsibility on nuclear planners in both countries to not only preserve deterrence but also minimize the probability of its failure through consistently seeking strengthening of mutual vulnerabilities. Hence the relationship between responsibility and deterrence goes like: the more the responsible conduct of deterrence (strengthening mutual vulnerabilities) the higher the probability of its (deterrence) success. Arguably, the prevailing doctrinal ideas and the developing sophistication in nuclear forces on both sides (India and Pakistan) tend to destabilize the mutual vulnerability reflecting irresponsible conduct of nuclear deterrence in the region.

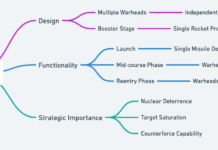

As per the requirements of deterrence, India and Pakistan have developed nuclear forces, however, the conditions pertaining to their deterrent postures are not overwhelmingly strengthening mutual vulnerability in the region. For instance, India maintains a credible minimum deterrent with a No First Use (NFU) posture that ensures massive retaliatory nuclear strike to ‘inflict unacceptable damage’ in case of any WMD (including biological and chemical weapons) attack on Indian territory and/or Indian forces anywhere. This NFU posture is inherently destabilizing, as it is likely to drive India irrationally to initiate a massive nuclear first strike during a (non-nuclear) military crisis in the region. On the other hand, Pakistan maintains Full Spectrum Deterrence (FSD) within the bounds of credible minimum deterrence to prevent war. The FSD is based upon a comprehensive targeting strategy encompassing battlefield, counter-force and counter-value targets at three levels of strategic, operational and tactical with appropriate weapon yield. This posture is endorsed by Pakistan’s National Command Authority as a response to Indian ideas of limited conventional fighting (Indian Cold Start and Pro-Active Operations) that are aimed to address the space within military spectrum left to sub-conventional/low-intensity war. The implied proportionality and flexibility within the FSD have lowered the nuclear threshold in the region. This is risky for the success of deterrence in the absence of escalation control mechanism that could effectively restrain sub-conventional/low intensity conflict within the required bounds.

The nuclear use, in addition, to inflicting unacceptable damage at any level in South Asia would be unacceptable for both India and Pakistan. The harm would be counted at three levels: first is related to the actual damage to human and material resource either in case of an attack or retaliation; second is related to the harm a nuclear attack will inflict on defender’s (nuclear armed defender) ego, along with resource damage, propelling retaliation; and third is associated with the burden both countries will have to bear as a result of breaking the non-use taboo. Therefore to initiate and retaliate with infliction of unacceptable damage – nuclear use, the causal responsibility (a subset of responsibility – who causes it) will be with the first-user. This attribution of responsibility to first-user is problematic: India’s massive nuclear first use against chemical and biological attack cannot be justified as it would undoubtedly invite a ‘severe’ response from Pakistan involving counter-value, counter-force and battlefield nuclear targeting. It is important to note here that deterrence binds a rational actor to hold back its nuclear use until adversary takes an unwanted action however, by no means, it allows a rational actor to arbitrarily prefer risking the destruction of the whole region, as rightly stated by David Hume, “to the scratching of [its] finger”. That is why it is imperative for both India and Pakistan to rationalize their doctrines and refrain from ideas (that are also translated into capability) that either drive nuclear planners to carry out disproportionate nuclear first strike in haste, or, advertently or inadvertently, lower the nuclear threshold.

With regards to capability, both India and Pakistan are developing robust and survivable nuclear forces capable of inflicting unacceptable harm on each other. This reflects that both sides are in control of keeping themselves vulnerable to each other. This vulnerability is important as it induces fear that tends to positively affect both India and Pakistan to steer away from danger. However, certain technological developments could gravitate region towards instability.

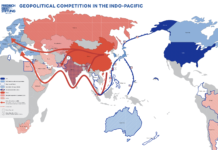

Comparatively, India is seemingly more vulnerable to Chinese nuclear force modernization than to Pakistan’s so New Delhi feels more responsible to maintain its vulnerability against Beijing, which in turn makes Islamabad more vulnerable. In such scenario, the causal responsibility lies with China to correct this equation whereas China is vulnerable to American nuclear posture and modernization. Simultaneously, Pakistan assumes task responsibility (it is your job to get it correct – another subset of responsibility) to manage its vulnerability. Therefore, in order to meet their deterrent needs, both India and Pakistan are developing sophisticated and credible nuclear forces in response to their evolving strategic environments. It is worth mentioning here that: 1) deterrence does not strictly imply developing a nuclear force capable of threatening and inflicting harm proportionate to adversary’s attack, and 2) deterrence is susceptible to technological breakthroughs especially when they amplify attack(s) with numbers and sophistication. The second point is particularly relevant to the new technologies introduced in the region such as missile defence shield and MIRV technology. Given the relativity in both states’ vulnerabilities, Indian development of ballistic defence capability to secure itself and Pakistan’s reciprocal development of MIRV technology to penetrate Indian defenses can be argued as plausible options to secure themselves against an attack and/or retaliation, yet these technologies undermine rival’s confidence in its ability to destroy/retaliate. Both technologies are inherently destabilizing for the deterrence stability therefore both states need to address this factor so that a stable state of mutual vulnerability is restored with a nuclear force that could promise mutual destruction.

The premise of nuclear deterrence is the normative non-use of nuclear weapons therefore it is the responsibility of both India and Pakistan to continue to uphold this norm. To ensure the non-use of their nuclear arsenals, deterrence between India and Pakistan relies upon maintaining: 1) mutual vulnerability and dependency among them with looming fears and risks that in turn compel both states to take responsibility of their situation and make efforts to strengthen it; and 2) the tragic necessity of threat of nuclear use whose credibility depends on a nuclear posture that is compatible to state of mutual vulnerability and guarantees mutual destruction. In addition, a responsible conduct of nuclear deterrence holds critical significance to the stability between India and Pakistan allowing more space for conflict resolution.

Dr. Salma Shaheen is a Lecturer at School of Economics and Law, London.