Muhammad Sharreh Qazi

‘Saudi Arabia reserves the right to arm itself with nuclear weapons if regional rival Iran cannot be stopped from making one’

Adel bin Ahmed Al-Jubeir

Saudi Minister of State for Foreign Affairs

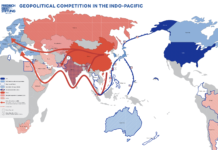

Israel opted for a deliberate ambiguous policy when it came to its nuclear capabilities and for a few decades such policy was working just fine; until Iran opted for the same, of course. With Israel’s recent ‘hearts and minds’ campaign in the Middle East and America leaving Iranian nuclear deal in limbo, there is what can be called ‘strategic inertia’ in how events will take shape in the future. Just around this thought however, Saudi Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Adel bin Ahmed Al-Jubeir points to something entirely out of Pandora’s Box. The big question that faces global audiences is this : Will Saudi Arabia, if current compression in Middle East resumes, opt for something more than conventional deterrence? Saudi Arabia has, ever since the incumbent administration, expressed reservations on Iran’s behavioral trajectory. Iran has often remarked how it does not intend to acquire weapons capability but somehow the world does not seem to believe it.

For Tel Aviv, concerns were somehow genuine as it was often the ‘intended target’ for Iran’s interpretable statements but now Riyadh shares the same apprehensions. For the Middle East and the Gulf region, time is fast approaching when nuclear deterrence might become a scenario beyond Iran-Israel rivalry. Though such discourse would not be the first time Middle East was seen as a potential challenge for nuclear non-proliferation but now the stakes are higher than ever.

Mohsen Fakhrizadeh’s assassination is a series of such events but as such incidents intensify, without any international arrangement binding Iran to incentives, prestige, and national security might persuade Iran to opt for a more overt retaliatory mechanism. Scott D. Sagan has already hinted at the causes and reasons as to states and their compulsions of opting for strategic weapons and nuclear deterrence. Sagan’s elements are profoundly based around regional vacuums and political necessities but are also based on social/domestic reasons pressuring states to determine their nuclear journeys. For Iran, unlike Saudi Arabia, the situation is almost how it was for Israel; surrounded by adversaries or latent observers collectively hamstringing national sustenance.

For Saudi Arabia, its recent Yemen (mis)adventure has exposed its national security infrastructure and its incapability of even managing conflicts in isolation. If observed through Sagan’s perspective, Middle East is terraformed for resorting to develop an overt nuclear deterrence, parties being Iran, Israel, and Saudi Arabia. Deliberate ambiguity between Iran and Israel has worked in curtailing conflict but with Israel’s connectivity in Middle East growing and Saudi Arabia’s military ambitions under current regime seeing augmentation, a triangular security dilemma is quickly asking for something more than conventional force posturing.

Iran, being a regional rival to Saudi Arabia, and Israel being an overall adversary to the world around it has already taken its toll in conventional confrontations and bellicosity. International intermediaries have already remained unable to reduce hostility in the region sometimes for want of national interest and sometimes for want of strategic dispositions. Donald Trump’s withdrawal from JCPOA negotiations and Saudi apprehensions only further confirmed Tehran’s assertions that it is being constricted and it cannot allow so. The only blockade in Middle East’s joining of nuclear club is Saudi Arabia still restraining itself from procuring or acquiring offensive capabilities.

The Royal Saudi Strategic Missile Force (RSSMF) is not yet as robust and equipped as its name suggests and Saudi Arabia still maintains a questionably offensive posture, focusing largely on defensive counter-measuring. Such strategies, though effective so far, have a limited shelf-life when adversaries/competitors continue to bolster their missile capabilities both horizontally and vertically. For Saudi Arabia the international perceptions of going nuclear are negative as global political arrangement exerts immense pressure on states opting to acquire nuclear weapons capabilities but as a threshold state, economically capable and militarily concerned, Saudi Arabia might be able to win favor.

Global non-proliferation regime and state practice cumulatively discourage more states from acquiring nuclear weapons and Saudi Arabia is already observant of numerous agreements within and beyond the IAEA, adhering not to divert its attention to a weapons program within its civilian nuclear programs. A major concern in this regard is not Saudi Arabia backing out of international commitments rather, it is Saudi Arabia and Iran collectively approaching a point in their conflict where they would eventually necessitate nuclear deterrence. Ballistic Missile Defense is an effective tool but Abqaiq-Khurais episode resonates just how ineffective such maneuvers can be and exactly how grave a risk it would be if a state were to solely rely on extended deterrence and ballistic missile defense capabilities. Whether Saudi Arabia would logout itself from global nonproliferation commitments is not an eventuality for immediate future but seeing how it now views Iran, a difference of approach is most likely on the table.

Nuclear weapons programs in contemporary global politics bring with them an astounding array of restrictions and sanctions, it is widely frowned upon with much paybacks but for sake of national interest and national security, a state cannot be deterred to adopt nuclear deterrence. If Sagan’s remarks are considered seriously, despite there being a strong nonproliferation regime and widespread denouncement of acquiring nuclear weapons, states have been known to jump the gun.

Iran and Israel have already polarized Middle Eastern politics beyond repair and minor issues have now become substantially peculiar in their solution. America has yet to decide whether it would resume or restrict further dialogue with Iran on its nuclear ambitions and it has definitely yet to disclose any incentives it might offer Tehran. Iran itself is quite far from where it was left in 2018 and has lost much in terms of economy and scientists. Israel might have been able to shake hands and accept garlands from Arab countries but its apprehensions with Iran have yet to be addressed. If there is a cumulative compression on Iran (like ones faced by North Korea) the result might be an acceleration towards nuclear weapons capability for deterrent purposes.

In such an eventuality, it would be difficult, nigh impossible to persuade Riyadh and more importantly Muhammad bin Salman, to not consider at least moving towards some arrangement guaranteeing deliberate ambiguity. For the Middle East, nuclear deterrence seems to be a likely eventuality beyond Israel and Iran and in such regard, Saudi Arabia stands out as a potent choice competitor/candidate. For Saudi Arabia, if there is a free pass for the sake of preventing influence of some global contender or to restrict Iran’s ambitions from snowballing, such free pass would be nothing short of a strategic victory in exchange of a strategic disaster.

Muhammad Sharreh Qazi is a defense and foreign policy analyst.