Salman Bashir

Pakistan needs to draw lessons post-Balakot attack on managing its security and foreign policy. The Indian attack on Balakot was an act of aggression. The drift in India-Pakistan relations touched a dangerous low with both countries coming close to full scale hostilities.

The fragility of the situation was demonstrated by the rapidity with which both Pakistan and India could climb up the escalatory ladder. It was the threat of a missile exchange between two nuclear powers, besides aerial combat and intensification of ground hostilities across the Line of Control in Kashmir, that eventually jolted the international community to take cognizance of the situation.

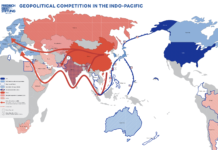

Friends like China and the U.S. intervened to calm the situation momentarily but real hardcore issues remain to be addressed. These are notably the grim situation in Jammu and Kashmir and the issues of strategic stability in South Asia.

India’s propaganda initiative against Pakistan had roiled up Indian public opinion to a war hysteria crescendo. It also found takers abroad. To lap the Pulwama attack on Pakistan was a travesty of facts. The attacker Adil Ahmad Dar was a Kashmiri and the Central Reserve Police Force, which is squarely responsible for unspeakable atrocities against the Kashmiris, would have seemed to him a legitimate target.

Pakistan had condemned the Pulwama attack and offered to cooperate with India in the investigations. Yet, US, UK, France and others latched on to the Indian version and went so far as endorsing India’s right to self-defense. This undoubtedly emboldened India to attack Balakot and to resort to the use of force against Pakistan with zero justification.

Pakistan thus found itself almost isolated and on its own on the early morning of 26 February. It was left with no option but to respond effectively and adequately to the Indian misadventure. This resulted in the downing of three Indian Air Force aircraft, within half an hour, two Indian fighter jets shot down by the PAF and an Indian helicopter that crashed during combat operations, becoming a casualty in the fog of war.

The capture of an Indian pilot became the face of the conflict and for sure demonstrated the capability and will of Pakistan to defend itself effectively. Subsequently, Indian threat of missile attacks was responded to by Pakistan’s ‘three for one’ retaliation posture that got the US to intervene.

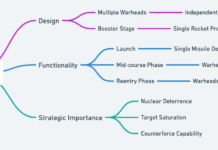

The post-Balakot episode brought to naught the Indian theory of arrogating to itself the right to take conventional military action against Pakistan in what was touted as ‘pre-emptive strikes’ – a contorted version of the so called ‘Cold Start’ – thinking that India’s conventional preponderance would enable it to establish its military hegemony over Pakistan, despite the nuclear overhang.

The Indian strategic and policy establishment has for years toyed with such ideas and coined dangerous and dubious doctrinal innovations to couch the use of force behind the right to self-defense. These notions need to be strongly rejected by the international community as patently self-serving and contrary to the UN Charter principles, including Article 51 pertaining to the right of self-defense.

The crisis has demonstrated that Pakistan’s own conventional and strategic capabilities alone are a guarantee of its security and under no circumstances could we rely on global peace implements to safeguard our sovereignty and independence.

The Pulwama-Balakot crisis also reinforced the view that India would remain an implacable enemy for the foreseeable future and the only way to manage it is by ensuring that our strategic and conventional capabilities remain adequate and robust.

However, the danger of isolated incidents igniting the nuclear fuse in South Asia is a horrific prospect with no fire walls for now. There is the need for putting in place crisis management mechanisms between Pakistan and India. This requires moving beyond signaling to a more credible and assured communication in times of a rapidly escalating crisis situation. Pakistan should be amenable to establishing and working with such crisis de-escalation mechanisms.

For now, the situation remains tense and uncertain. It is probably worthwhile for major powers such as the US, China and Russia to encourage initiatives for peace and security in South Asia and reinforce the concept of Strategic Stability.

Ambassador Salman Bashir is a former Foreign Secretary of Pakistan and Ambassador to China, India and Denmark.