Saeed Afridi

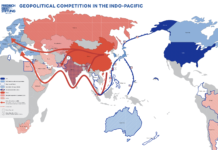

It can be argued that the demise of the US’ unipolar moment lay in the hastily ill-conceived ‘War on Terror’ in the wake of the World Trade Centre attack. The US embarked on a series of interventions that interrupted the gradual assimilation of regional powers into the US fold, among them is Iran. Despite having considerable congruence with the United States’ stated goals, Iran found itself among the US’ ‘axis of evil’ and a virtual neighbour to US presence in Iraq and Afghanistan. The War on Terror provided Iran with the first real opportunity in almost a century to carve out a regional policy wholly dependent on Iran’s own interests, rather than those of an external power. As a regional power with a sphere of cultural, religious and historical influence extending beyond its borders, Iran embarked on a series of regional measures that allowed it to play to its strengths. As the unipolar moment waned and multipolarity began to emerge, Iran was better placed to gauge and take advantage of the relative strengths of the multiple powers vying for influence in West Asia as well as fill the vacuum left by their weaknesses. Cooperating with multiple powers to encourage inter-dependency within regional frameworks is the mainstay of smaller regional powers in a multipolar world.

Multipolar world becomes a catalyst for regionalism as regional powers see greater economic integration of the region as a means to emerge as global competitors. Iran’s geographical area of influence has historically had a core region which largely corresponds to Iran’s political boundaries of today. However, during previous Persian regimes that have risen to hegemonic status within the region have done so by physical expansion into Central Asia, Western Afghanistan, Eastern regions of what is today Iraq and western regions of what today constitutes Pakistan. Iran may consider expansion of its influence in these areas as a precursor to emerging as a politico-economic contender in a multipolar world. Rather than rely on a confrontational physical expansion of its borders, Iran has begun a process of reintegration into the economic activities and trade of these regions. Iran’s foreign policy is now reorienting itself towards a greater role in its historical sphere that spans from the Levant in its West, the Central Asian republics to its North and to the Ganges plain in its East.

Despite its concerted policies to export its ideational revolution to its immediate region, Iran’s newfound expansion of influence beyond its physical borders has been a result of Iran’s engagement and considered positioning with contending global powers, including the United States.

Iran & the United States

Iran opted for neutrality during the First Gulf War between Iraq and the United States, which may have assisted to a lesser degree in the inevitable US victory. The US invasion of Afghanistan was assisted by Iran through its network of allies within Western Afghanistan and its influence with the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance. Iran’s attempt to ingratiate itself with the US was unceremoniously rebuffed when it was included in the ‘axis of evil’. Though this may have been a result of the US-Israel relationship, it nonetheless put considerable strain on Iranian attempts at rapprochement towards the US. The policy faltered completely once the US rebuffed Iran’s attempts at striking a ‘Grand Bargain’ in the aftermath of the Second Gulf War and the America’s near unilateral invasion of Iraq. Miscalculating the success of the Iraq invasion, US ended the Zarif-Khalilzad dialogue in Geneva and instead embarked on a course of regime change through the political destabilisation of Iran by providing material assistance to Kurdish and Baluch insurgencies. As the invasion of Iraq turned into a protracted conflict, the US came under repeated attack by largely Sunni insurgents backed by its own Gulf allies. US insinuations of an Iranian role defied the ground realities and the use of pro-US Sunni outfits to attack largely Shia populations in Iraq provided Iran with the opportunity to solidify its hitherto weak cooperation with Shia outfits hesitant to accept Iranian assistance. By the end of the decade, Iran had firmly established proxy control over much of the South and Central regions of Iraq and also placed itself as the main ally of the Iraqi government in its coming battle with the largely Sunni-Wahabi-Daesh nexus, or Islamic State. By the end of the conflict in the early 21st century, Iran had emerged as the most powerful political player in Iraq through a working anti-Kurd alliance with the second important regional power in Iraq, Turkey.

Iran and Russia

During the decades of internal political as well as economic instability, Russia’s presence on the international stage diminished to the point of near irrelevance. Rather than presenting an alternative to the US vision of the world, Russia became an object of it instead. Internal reforms inspired by the Washington consensus had ushered in a period of extremes in the Russian society and regionally Russia retreated from even its most entrenched presence in Central Asia. After these initial years of what became known as Euro-Atlanticism, the first concerted vision towards a Russo centric policy of foreign relations emerged in the form of “Eurasianism”. At the outset, Eurasianists strived for regional and foreign relations based on mutual interests linked to the Russian state, rather than ideationalism or idealism. Though this included non-confrontation with the United States, its mainstay was to forge relations with other regional powers to advocate and facilitate the emergence of multipolarity, though the preferred term used was multi-vector diplomacy. Despite its own troubles with Muslim separatists, most notably in Chechnya, Russian Eurasianists considered Muslim countries, and Shia Islam in particular, as a natural ally in the quest for multipolarity. Eurasianism drove Russia’s re-engagement in the Caucuses and Central Asia found in Iran a partner with mutual interests. This soon extended to the anti-Taliban alliance in Afghanistan. With Putin’s Russia playing a more assertive role in the Middle East and Central Asia after the US faltering in both Afghanistan and Iraq, Iran’s relations with Russia improved considerably despite conflicting views on Iran’s nuclear ambitions and interest in the Caspian Sea. Iran’s membership of the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), linking Russia, the Caucasus, Central Asia and Iran to a sea based trade route with India was an example of this new momentum. As Russia’s role in the Middle East grew, so did that of Iran and the culmination of this partnership came about with the civil war in Syria. Over the course of the conflict, Iran through Russian assistance was able to place itself as the most important regional player within Syria in particular and the Levant as a whole, to the great detriment of US and Israeli interests.

Iran and China

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Central Asian Republics presented Iran with an opportunity to expand its influence as Russian dominance waned. However strained relations between the US and Iran acted as a formidable barrier as the new republics remained cautious of US reactions towards greater ties with Iran. Competing with Turkey for influence, Iran found itself having a considerable disadvantage due to the promotion of its Shia ideational measures in a predominantly, albeit loose, Sunni region. Pan-Turkism held more sway in the initial years and Iran, still under sanctions was unable to match Turkey’s prowess for economic and industrial assistance.

Iran’s efforts to further transportation and trade links in Central Asia under the umbrella of the ECO also suffered mixed results, limited in part by Iran’s own industrial capabilities. It was not until the advent of China into the region as a trade partner, first under the structure of the SCO and then under CAREC that Iran finally began to solidify its position in the region. After the launch of China’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), termed the New Silk Road, Iran found itself in a pivotal role encompassing not just Central Asia but also Afghanistan and Pakistan. The elaborate BRI included a set of six land-based corridors to enhance trade between China and the entire Eurasian continent. The most elaborate, ambitious and difficult to realise of these corridors is the China-Central West Asia Economic Corridor (CCWAEC) which links China with Turkey through four Central Asian Republics and Iran. The importance China places upon Iran in this corridor is evident from the ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’ agreed with Iran in 2016 and the slew of coordinated efforts both countries have undertaken to enhance trade between the Central Asian Republics who are members of the corridor. China has greatly assisted coordination between SCO and Iran as well as CAREC and Iran, enhancing both Iran’s trade ties within the bodies and assisting in furthering Iran’s influence, something Iran failed to do on its own for more than a decade after the Soviet collapse. Iran’s muted stance, compared to Turkey, on China’s internal problems in Xinjiang is a further indication of the lesser importance Iran has placed on the ideational aspect of its foreign policy, at least with respect to China. As China expands its reach through investments in port facilities in both Turkey and Greece, Iran’s ability to trade with Europe is being enhanced as part of the corridor. China’s significant investments in upgrading Iran’s transport and energy infrastructure, including railways and dormant gas fields, has also improved Iran’s position in regional trade. Improvements in Iran’s trade and Energy infrastructure through cooperation with Chinese firms has led to a resurgence of Iranian influence in Central Asian Republics at a level not witnessed since the mid 19th century.

China’s BRI has also provided Iran with an opportunity to slip back into a region that has historically been susceptible to Iranian influence for millennia but has since the beginning of the 20th century remained largely devoid of any significant Iranian political or economic presence. Along with the CCWAEC, China is also developing another corridor as part of the BRI with Iran’s Eastern neighbor Pakistan. The China-Pakistan economic Corridor (CPEC) inherited much of its framework from previous agreements under CAREC and has been easier for China to advance but its significance for Iran has not gone unnoticed in Tehran. Both China and Iran consider greater co-operation between Iran and Pakistan in order to ‘link’ the two corridors as an eventual goal. Iran has made several overtures to Pakistan to increase cooperation and as Chinese investments in both these corridors gain pace, the eventual linking of CPEC and CCWAEC seems to be inevitable. Once linked, Iran would act as a pivotal trading state between the key economic entities of Europe, Russia, China and India.

Despite being an important regional entity for much of recorded history, Iran was unable to assert its influence within its immediate region during much of the 20th century. Lack of a concerted and Iran-centric foreign policy devoid of external influence throughout much of the past century meant that Iran was not in a position to truly take advantage of the opportunities presented to it in the immediate aftermath of the Soviet collapse. During the unipolar moment Iran found itself largely contained within its physical borders and its ideational influence mostly curtailed. The emergence of a multipolar world allowed Iran the opportunity to enhance its cooperation with emerging powers and use their initiatives to further its own regional goals. As the second decade of the 21st century approaches a close, Iran has found itself in an enviable position to first expand into its historical sphere of economic, political and cultural influence in the Levant, Central Asia, Pakistan and North India and then embark on a future course to solidify its position as a major trade conduit in its immediate region as well as the larger Eurasian economy.

Saeed Afridi is an Energy Security Researcher, University of Westminster, UK