Syed Ali Zia Jaffery

“We will not hesitate to use any weapon in our arsenal as our security is more dear to us than the advice of international leaders which is one-sided “, said Pakistan’s then Foreign Secretary, Shamshad Ahmad Khan, during the height of the Kargil Conflict in 1999. Fast forward to January 2002 and phase one of the Twin Peaks Crisis, Pakistan’s strategic doyen and the then Director General of the Strategic Plans Division (SPD) , Lt.Gen Khalid Kidwai laid out the conditions meriting Pakistan’s use of nuclear weapons. These two statements across crises were not mere nuclear signals but also expressions of the country’s will to use the ultimate weapon against its adversary India if the redlines were ruptured. Needless to say, such enunciations have been the guiding principles of Islamabad’s nuclear trajectory.

In her latest article entitled “Nuclear Ethics? Why Pakistan Has Not Used Nuclear Weapons…Yet,” Sannia Abdullah argues that Pakistan’s nonuse of nuclear weapons is neither a result of deterrence nor a taboo but a product of Pakistan Army’s adherence to the military-utility principle that panders to its organizational interests. This proposition is strange since even a cursory look into the dynamics of the Indo-Pak nuclear dyad reveals the prominence of deterrence.

Over the years, Pakistan has expanded its arsenal, delivery systems, started seaward nuclearization, and shifted its doctrine. All this has been done to augment its deterrence mix vis-à-vis India, something that has strengthened bilateral deterrence between the South Asian nuclear dyad.

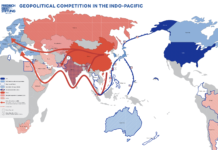

Despite threats to deterrence stability and the outbreak of three crises post 1998, bilateral deterrence has played a great role in crisis management in the ever so volatile South Asian region. The agency given to third parties’ mediation and crisis diplomacy circumvents the fact that it was the presence of Pakistan’s deterrent that gave Washington or Beijing time to arbitrate between India and Pakistan. This argument is valid in peacetime and during a crisis. India’s refrain that Pakistan uses the nuclear bluff and gets away scot-free, is a simple way of acknowledging this: Pakistan’s nuclear weapons continue to deter India from hurting it. If one puts it in the parlance of strategy, Pakistan’s deterrence mosaic is undermining India’s compellence tools. Also, the idea of exploring military options under the nuclear umbrella, regardless of nomenclature, points to the fact that deterrence partly outlawed massive Indian incursions into Pakistani territory envisaged in the Sundarji doctrine. Pakistan’s territorial integrity was not violated in 2002 like it was in 1971, despite India’s growing conventional superiority, because of its nuclear capability and the will to use it. What emanates from this discussion is the inextricable link between nuclear deterrence, nuclear threshold and nuclear use.

As evident, nuclear deterrence continues to dissuade India from breaching Pakistan’s thresholds and leaves no rationale for Pakistan to use nuclear weapons. This also amplifies the need for bolstering deterrence. While trying to navigate through Pakistan’s deterrence, India’s limited war doctrine often dubbed as Cold Start, imperils Pakistan’s redlines. Aimed at deterrence enhancement and gap-plugging, Pakistan’s Tactical Nuclear Weapons (TNWs) are an antidote to the Cold Start Doctrine. The threat to use TNWs is not only a measure to buttress deterrence but also a reminder about the sacrosanctity of Islamabad’s spatial and military thresholds. The purpose on part of Pakistan is to signal India its intent to use nuclear weapons, tactical or strategic, if the clearly articulated thresholds are violated in case of deterrence failure. If anything, India’s efforts to undermine Pakistan’s deterrence and threaten the threshold will determine whether Pakistan uses nuclear weapons or not. Even if one takes the argument pertaining to military-utility on face value, the role of deterrence becomes all the more important. As a matter of fact, the essence of deterrence lies in turning viable military options into risky and untenable ones.

The hypothetical scenarios of Pakistan’s nuclear use penned by the author are directly linked to deterrence and its failure. The author’s supposition of Pakistan targeting the Jaiselmir Airbase is a tad problematic. Firstly, as mentioned by the author, it is a first strike that has a different meaning and connotation all together. Secondly, the disutility of hitting that very desolate counterforce target is in consonance with the tenets of classical deterrence theory. According to Andre Beaufre, a state with scant riposte capabilities is likely to achieve defensive deterrence which may not enable it to react to an attack on its territory, but India has retaliatory wherewithal. India’s nuclear forces would be well intact and ready to respond to Pakistan’s Jaiselmir’s adventure. Therefore, a basic understanding of deterrence is enough to deter Pakistani strategists from carrying-out such a decapitation strike.

That said, there is no doubt that there is no nuclear taboo in Pakistan. In fact, expecting any Nuclear Weapon State (NWS), operating in an anarchical order, to factor-in ethics is unreasonable. However, the recommendations given by the author are rather discursive. There is literature available that substantiates the fact that Islamabad’s nuclearization was a brain child of a civilian leader. Also, there is evidence to support the claim that both, the military and the civilian leaders were resolute and unflinching in getting a deterrent for their country. The argument that posits the military as hawkish and civilians as pacifists does not stand the test of research. As rightly pointed out by the author, the nuclear tests united everyone across the highly-touted divide. Thus, Civil Military Relations (CMR) have had little to no impact on Pakistan’s nuclear direction. Moreover, CMR has no bearing on India’s conventional and strategic modernizations that deride Pakistan’s deterrence.

It is noteworthy to mention that, regardless of insinuations and the “Islamic Bomb” bogey, neither Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal provides extended deterrence to the Muslim World nor Islamic injunctions feed into Pakistan’s nuclear strategy. Hence, invoking Islamic teachings to pull off a taboo or an end to no first use policy is rather untenable. In fact it would lead to more bellicosity than restraint, especially given the differences between scholars, sects and their general aversion to India.

Pakistan is a responsible NWS; it will Always be ready to strike but Never to strike other than under the conditions outlined by Gen. Kidwai 17 years ago. The state of the bilateral deterrence equation will determine whether an irrationally rational decision is taken or not. To expect civilians to detest using the nuclear device if Lahore is captured and the Army decapitated to wrest it back, is very difficult. The equation is simple: so long as the four thresholds remain impregnable, Pakistan will not replicate the United States’ carnage of August 1945.

Syed Ali Zia Jaffery is a Research Associate at the Center for Security, Strategy and Policy Research, University of Lahore.